Upcycling brand Threadapeutic is aware of the urgency at hand. The waste generated from fashion, one of the world’s most polluting industries is both alarming and humbling, more so to founder Nagawati Surya – better known as Hana – who witnessed firsthand the throwaway culture of one fashion event in Jakarta during her freelance stint in 2015.

There, Hana was tasked to create souvenir bags by reusing post-event banners and leftover fabrics from deadstock. “[The event’s organisers] asked my team and I to do something experimental,” said Hana. “We made over 200 bags and received a good reception. For the fashion community at the event, it was also their first introduction to upcycled bags.”

At the time, the idea of utilising fashion waste was already mushrooming into the industry’s conversation, but dedicated platforms were scant. “It got me thinking of how upcycling can be a source of a sustainable business venture because even though they are waste, they are raw materials after all.” It opened a fresh prospect for Hana, who before starting Threadapeutic in 2015, was a homemaker. “I was never a career-minded person,” said Hana. “This thing sort of fell out of the sky and landed on my lap, which I happened to like and found purpose in.”

But it wasn’t totally out of bounds for Hana, who grew up learning simple sewing techniques from her seamstress mother. Spending her time between Jakarta and Singapore, the Pepperdine University alumna finds sewing – be it when she has to mend a tear on her daughters’ clothes or shorten the hem on their skirts – to be therapeutic (hence the name).

The road to circularity

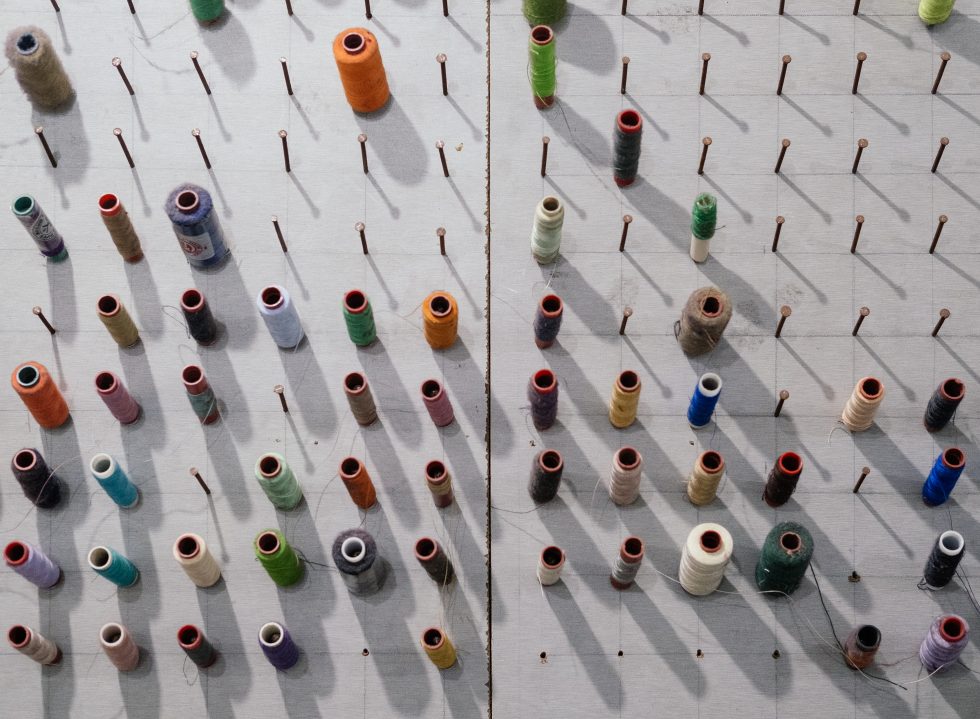

The drill at Threadapeutic is to create products from offcuts through fabric manipulation called faux chenille, a technique Hana learned from her designer cousin. The offcuts, collected mainly from partnering local garment factories and fashion ateliers to interior houses, are layered and stitched to create the brand’s lineup of bags, tapestries and masks. “This technique allows us to use small pieces of offcuts. Even the narrow ones can be layered into a new fabric,” explained Hana. “[Faux chenille] also creates this smooth, furry texture which is a result of the brushing technique that comes with the process.”

Hana’s small yet reliable band of artisans has been operating from their workshop in Palmerah. Hailing from diverse backgrounds, there’s Pak Udin and Pak Kusworo, senior seamsters who’ve been in the field for years respectively. There’s Ibu Jeanne, who handles administrative work, along with the design of their banner bags and Ibu Fitri, who’s deaf from birth, works mainly with fabric cutting while doubling as an assistant to Pak Kusworo.

In the beginning, the team only did basic patchwork, but a lot of experimentation was done to get to where they are today. “We have to recognise fabric textures and learn how to combine them because we are not just working with cotton or linen. [With offcuts], we have to take everything that comes our way.”

Besides fabric offcuts, Hana also explores other waste materials such as post-event banners, which she usually gets from event companies, as well as coffee sacks, in which she gets mainly from the coffee roastery, Morph Coffee (who is also the main supplier of One Fifteenth Coffee). Recently, the team also received pieces of coffee sacks from Glyph Supply Co cafe in Singapore to be upcycled into ready-made products for them. “It’s not just about the line of products that we have, it’s about catering to different waste problems.”

Which is why, on top of being labour-intensive, upcycling is an artisanal work at the core. The high price points, which become both a challenge and a dilemma for the brand, is a reflection of this laboured effort. “Many people tend to think that because it’s upcycled, it has to be cheap,” said Hana. “The main point is to create something that doesn’t look like it’s derived from waste.”

Quality over quantity, but in the end, it’s also about prolonging the life cycle of each product. “We are part of circularity, not the whole system,” stated Hana. “When we make products, we make sure that it’s easy to be repaired and there’s a continuous usage for it.” The brand also welcomes outworn bags that the customers bought from them to avoid another waste in the dumpster. “This is our attempt to keep the products circular.”

This year’s resolutions

A recent addition to Threadapeutic’s lineup is the chenille wall panel, which currently takes over the brand’s main line of work outside fashion. “This year, I would love to go more into interior products. Fashion is too complicated,” Hana laughed.

The first one, titled ‘Purple Reign’ is a stunning 11m x 7.15m piece made out of over 90kg of fabric offcuts. Constructed together by in-house artisans and workers from partnering garment factories, the wall panel now sits at BTPN Tower in Mega Kuningan. Soon after, Threadapeutic was offered their second wall panel project, which was done during last year’s pandemic.

Like many, the tumultuous 2020 was a wake-up call for Hana, especially on what it means for the fashion industry. “It forced us to reexamine our own productions, from the raw materials we obtain to how we market them. Everyone seemed to be talking about sustainability, but I think it’s due time for everyone to change.”

On a personal level, Hana also found herself practising mindful shopping as to not create more waste, and she claimed it to the nature of her work at Threadapeutic. “I think if you do this regularly, it changes you and I hope it changes my team as well because at least they know that waste can be turned into something valuable,” concluded Hana. “It’s step-by-step. We can’t force people to change if we don’t do it ourselves.”