One of the great pleasures of Sejauh Mata Memandang’s show is that designer Chitra Subyakto is not one to burden herself with complicated references and stories. Her grip has always been firm on the women she’s dressing, as well as the ‘responsibly-made’ angle that has served as an important cornerstone of the label.

One of the key highlights this season is the use of selvedge denim. Although Chitra has incorporated denim in past collections, she has confidently expanded her take this time around; threads, some derived from recycled textile waste and handspun cotton thread, as well as indigo and secang (sappan wood) dye, were utilised to create selvedge denim with softer quality and varying tones.

She showed a fantastic kebaya-inspired embroidered denim blouse paired with a denim skirt. The clean lines and ease at which the denim hung on the model were irresistible in its relaxed attitude. Most importantly, Chitra injected the looks with a clear intent and purpose, which comes as no surprise given that Chitra was a costume designer before starting her label. All the models moved like they had somewhere to be. The aforementioned look wouldn’t be out of place in a business lunch meeting. In another, a model in denim overalls peppered with embroidery patches in the shape of the label’s signature rooster has the quality of an insouciant art student.

Chitra is not someone who is preachy about the sustainability aspect of her label, opting to lay out the proper groundwork through responsible sourcing and lasting design instead. This season though, spurred by the continuous deforestation and effects of climate change in the country, she closed the show by marching with models who carried banners that called attention to environmental issues. And just like the collection itself, they carried substance in their intent.

Sean Loh and Sheila Agatha of Sean Sheila may seem a little unsure of themselves this season. Though, that’s not to suggest they are not moving forward. One of the clearest examples is the blurry atmospheric print of lily flowers on two of the looks. The print was achieved by applying it directly onto the finished garment, giving it an out-of-focus effect.

In the past, the designers have consistently sent out various looks with flower embroidery. So to preface those blurry prints with a white shirt displaying sharp flower embroidery, in which big lapels peek out of the black blazer jacket, was the right move. There’s also a sense of the pursuit, and the loss of security in the pieces—a thin band extends from the sleeves of a suit jacket to hug the chest across the lapels, threads unravelling from the seams of a denim jacket.

But viewed as a whole, the collection did not come across as clearly as it should. For instance, the final look of the deconstructed dress conveyed a competing idea. Given more time for exploration, Sean and Sheila would no doubt find a sharper aim and run with it confidently.

Still, the idea of things unravelling and going out of focus also felt apt in this uncertain time. Especially with the Israel-Hamas war happening on another corner of the globe that has challenged beliefs and forced many to confront that ethics isn’t simply black and white.

Mahija delivered a fantastic show under the banner of Dewi Fashion Knight that closed the Jakarta Fashion Week. The Yogyakarta-based jewellery house often collaborates with local designers as a strong supporting cast to their collections. That’s why it was great to see how designer Galuh Anindita told the story her way in this show.

The course of creating the pieces was a labour-intensive process that involved wax carvings as well as moulds that required continuous recarving and reshaping. Post-show, Galuh mentioned that some adjustments were made in the making of the bodice. For the latter master mould, modelling clay (an oil-based type of clay) was employed as the weather was too hot in Yogyakarta. From there, silicone mould was created, and then the resin, and more adjustments were made. “So it’s actually akin to making a statue,” she said.

While the labour that went into the pieces may not be easily detected by showgoers, the show hit the emotional button nevertheless. The essence is firm in its core of exploring the theme of death, the idea of decay. But it also opened itself up for different interpretations in a way that involved viewers to take part in deciphering the show, allowing them to ask questions and contemplate the answers.

In one body piece, a centipede is shown beside a heart. If one could consider butterflies as beautiful, then why is the same not afforded to centipedes? And the hearts! What a great way to wear your heart on your sleeve, and in this case, on your body or even carry it in a small clutch bag. Jewellery piece not as a form of armour, but to give yourself completely into the vulnerability.

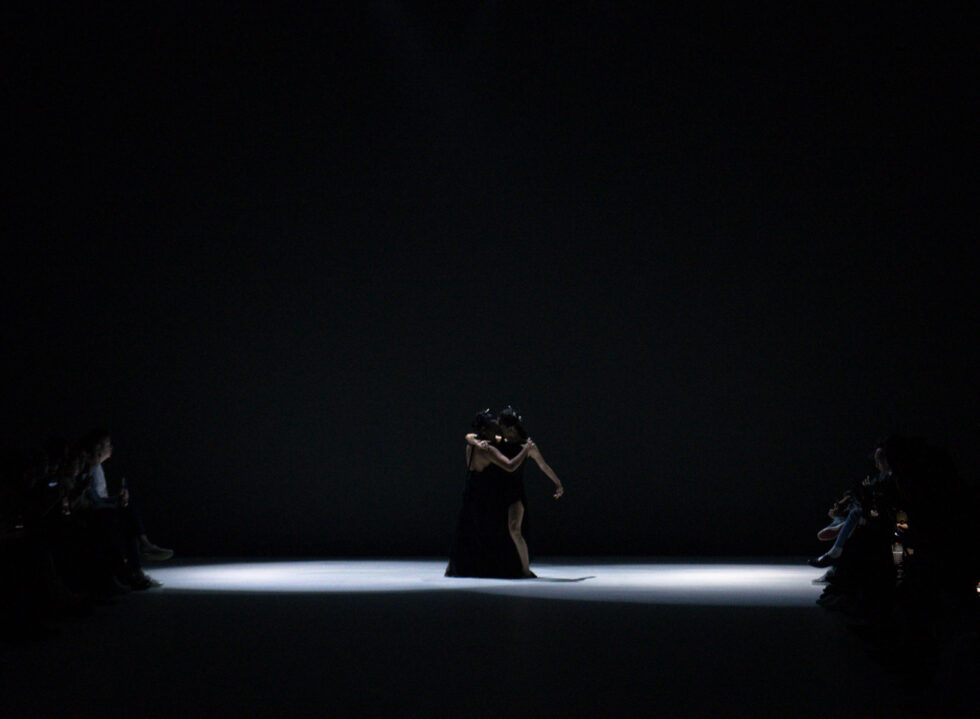

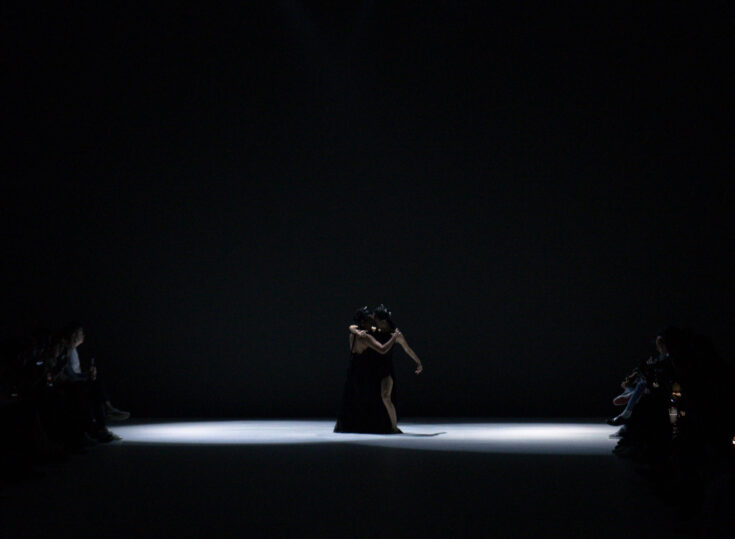

Also, the Javanese dance performance that accompanied the show was a genius way of expanding the context of the collection. Performed by Kinanti Sekar Rahina and Jasmine Okubo, it told the story of Srikandi, a reincarnation of Princess Amba in her past life who sought revenge on Prince Bisma. Though the actual story may be lost to many of the viewers, the Javanese dance performance provided an engaging footnote to the show.

As an art form, Javanese dance offers philosophical and spiritual narratives that challenge us to observe the transgression of opposites. In one masterful stroke, Galuh addressed many points in one go—the non-binary quality, the fluidity of the pieces that take on different interpretations under different wearers (more evidently through Mahija’s collaborations with different designers) as well as touching on the city in which Mahija is based in. There was light in its darkness. It was romantic despite its melancholy. It was poetry incarnate.