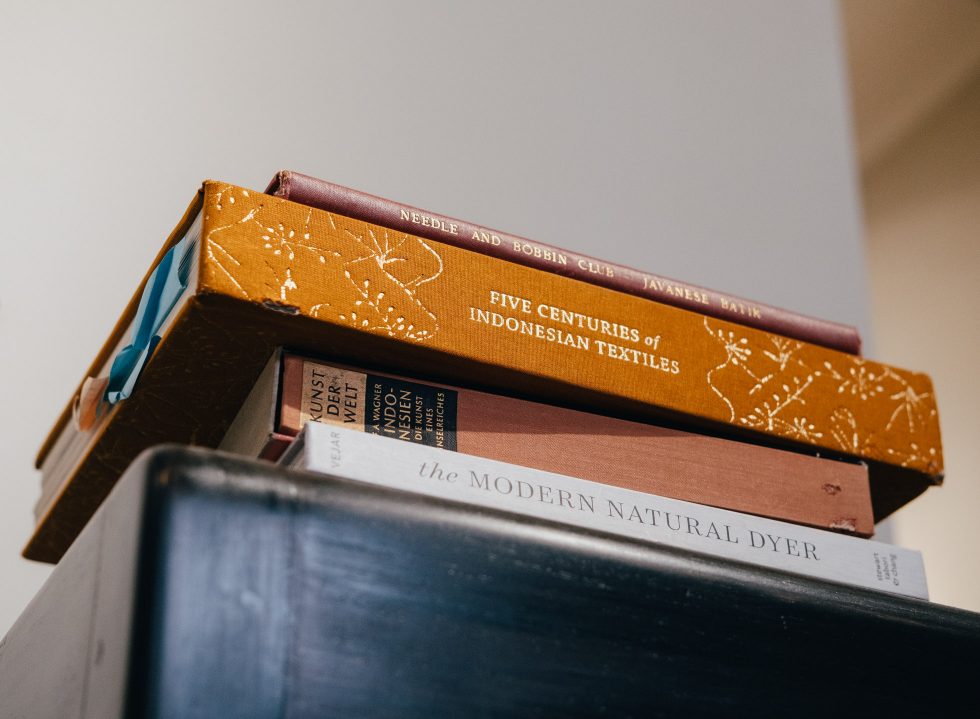

For centuries, traditional crafts such as batik, dyeing and handweaving have been passed down from one generation to the next. Up until the discovery of synthetic dyes in 1856, Javanese textile houses were still growing their cotton, hand-painting batik motifs and dyeing their fabric using gathered plants from the forests, forging recipes and techniques that were put aside when the promise of a quicker, more profitable option surfaced.

“It was only 200 years ago, before textiles underwent mass production, that our ancestors were draped purely in clothes dyed using plant-based recipes. Seeing the huge disconnect today, we saw the urgency to draw from local knowledge and return to these traditional processes,” shared Denica Riadini-Flesch, founder of social enterprise SukkhaCitta.

At SukkhaCitta, their values have always looked beyond just clothes, focusing instead on empowering craftswomen, preserving traditional crafts and ensuring livable wages for the artisans. Aware of the lifetime impacts of our consumer habits, they work together with their ‘Ibus’ to trace back traditional recipes and techniques of their grandparents to bring a slower, and as a result, a more in-step-with-nature method of doing things.

With more consumers turning their gaze to environmental impact and traceability, other brands like Canaan Bali and Jogja-based SAKA Studio have adopted a similar approach, favouring the traditional way of doing things and embracing the spirit of discovery when it comes to botanic dyes.

One with nature

When Emmelyn Gunawan, founder of boutique shop Canaan Bali, was sourcing locally-made room amenities for Katamama at Desa Potato Head back in 2016, she was already working closely with several craftsmen and artisans in Bali. From observing carpenters and rattan weavers to natural dyers, she developed a combined sense of curiosity and admiration for local techniques and materials which quickly found their way into the brand’s line of products.

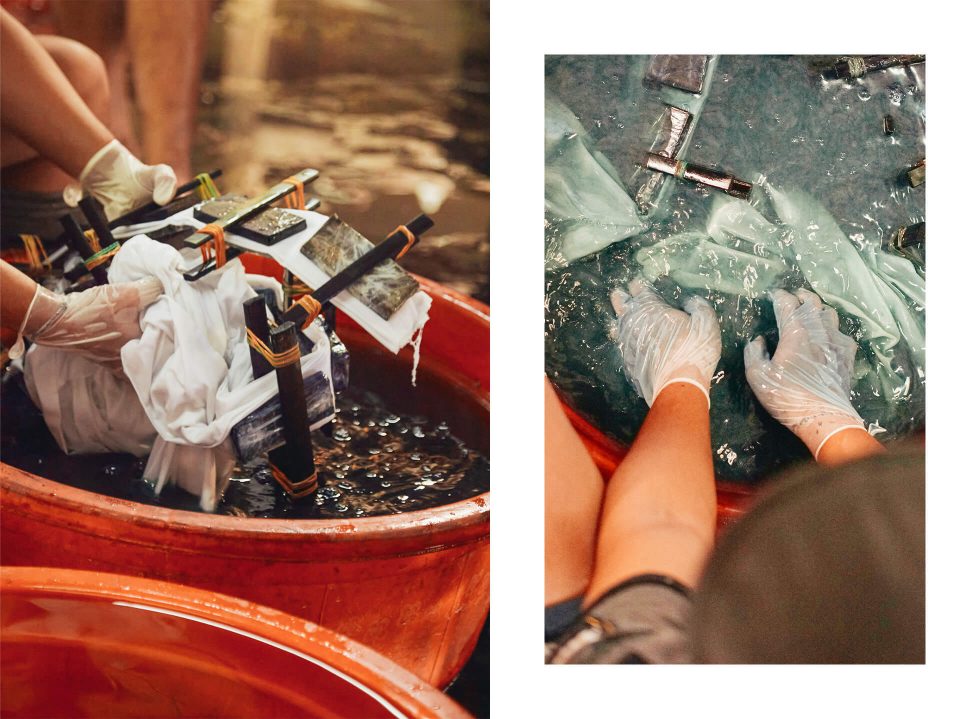

For starters, the brand’s collection of shibori tees features bamboo cotton dyed using the popular Japanese shibori method and pigments extracted from plants, seeds and wood barks in collaboration with independent craftsmen and natural dyeing house Tarum in Gianyar.

Their latest exclusive collection for concept store Escalier displays loose-fit t-shirts and short-sleeved shirts patterned in contrasting colours derived from various plants which can be found across the island; especially mango and mahoni leaf, Indigofera plants and wood barks.

Across Canaan’s collections and loud hues of indigo and forest green, ochre yellow to terracotta, Emmelyn found that “even if we use the same formula and the same dyestuff, every batch will come out different. We’re talking about natural factors here, like sunlight, air temperature, humidity and water quality. The results can be quite unpredictable, but what’s constant is this heightened awareness of what’s really around you.”

Likening the process to seasonal eating, Denica shared that “at SukkhaCitta, it’s always been about learning to produce clothes that follow the rhythm of nature as opposed to forcing the planet to follow our business calibre.”

Some colours are more obliging depending on the time of year. The greens, for example, can only be processed during dry season as it needs a constant streak of sunlight. “It teaches us to be human, to be more in tune with nature and the rhythms that are already there,” Denica went on to add.

Connection matters

The same sentiment is also shared by Stefanie Jessica and her fashion label SAKA Studios. Based in Jogja, the brand started during the pandemic after she observed how much vegetable scraps her family accumulated daily during their stay-at-home period.

While one might assume that easy-to-stain materials like beetroot and turmeric create potent hues, Stefanie’s kitchen experiments would easily dismiss the thought. Her explorations eventually settled on shallot skin, which she began to collect from the market, small restaurants, neighbours, as well as her own kitchen. At first, her inquiries attracted a mixed response, from puzzled looks from shopkeepers at the market to her grandmother playfully asking her “why are you playing around with trash?”

But for Stefanie, it was important for her to find the intersection between something she is passionate about (fashion) with something she cares for (nature). SAKA, which translates to ‘from’ in Javanese, is her way of “creating a second life for kitchen waste that would otherwise be thrown out and to echo a more circular cycle,” the designer shared.

This value extends to SAKA’s production process, from using collected rainwater for dye baths and saving leftover shallot skin for compost, utilising recycled paper for tags to gifting a pouch of lerak (soapnuts) with every purchase, empowering customers to also develop a more meaningful connection with the clothes at home.

With the help of a small team of local makers, their debut collection, MULA, was dyed in small batches in her back garden, resulting in a collection of trousers, skirts and dresses in an earthy spectrum of soft-hued beige to brown.

Similarly, it was also through multiple trials and testing that SukkhaCitta obtained its signature shades. Their yellow, for example, was extracted from a mythical tree in a little village in Gunung Kidul, Central Java. “The villagers there believe the tree is sacred so nobody dares to climb it or cut it down. But once a year after the rainy season, the women will pick up the fallen symplocos leaves, which are then dried and boiled to release this beautiful shade of deep yellow.”

A remedy to mindless consumerism

Still, the process of plant-based dyeing is not as simple as gathering plants and simply squeezing out colours. A lot more goes into creating a workable solution that would stick to the fabric, with processes like mordanting and reduction still often involving a lot of heavy chemicals.

Different materials also call for different extraction methods, from crushing and boiling to fermentation. Again, each dye works under different formulas and conditions, sometimes requiring multiple rounds of soaking in dye baths and drying depending on the shade desired.

“Through the process, I started to understand that to be effective with plant dyes, you also need to develop a natural process to go with it. Going back to the recipes of our ancestors, when reducting our indigos, for instance, we mix the leaves and fermented water with Javanese palm sugar instead of chemicals. Not only is this safer for our dyers, but it’s also kinder to our planet,” Denica added.

This idea to restore the system from the ground up has always been central to SukkhaCitta and their practice. Not stopping at natural dyes and complete traceability, the brand also started farming their indigo leaves and in 2020, established their regenerative cotton farm.

And sure, working with plant dyes comes with “a lot more research, testing and time” Stefanie admitted. But for the SAKA designer, it’s a process worth diving into, as she sees how her customers seem to be open-minded with the idea and excited to see what the brand comes up with next.

The same spirit of discovery echoes in Canaan. Emmelyn explained how “it’s not a simple route with plant dyes. The imperfections, discoveries and at times inconsistencies of natural dyeing is what makes it unique. Plus, having the privilege to work with local artisans to bring their craft back, that’s important to me.”

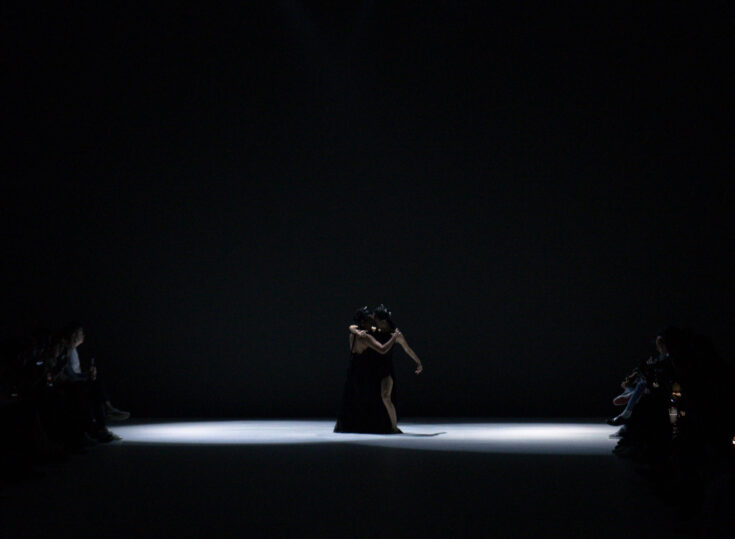

As for Denica and SukkhaCitta, “helping the craftswomen, or ‘Ibus’ in our village retrace their grandmother’s recipes and connect with their heritage in that way, that’s special. It all boils down to connection, from nature to the makers to our community. I believe that’s the antidote we have against consumerism.”