The week-long Jakarta Fashion Week, which was supposed to wrap up last Friday, was pushed to Monday evening instead in respect to the inauguration of President Joko Widodo the week before. It must have sent the entire JFW crews and designers into panic mode–scrambling to readjust to the change of schedule, re-inviting guests and so on, but for the fashion week to happen right after such a significant national affair should be welcomed as symbolic: the second term promises a new start and fashion can be a language to drive and convey the aspirations and anticipation of what’s to come.

As per usual, JFW is concluded by the Dewi Fashion Knights (DFK) show. Every year, the latter (under a panel of juries from Dewi magazine) selects at least four crème de la crème designers to showcase the best talents in the country under a unifying theme. This year, it was “Borderless”. To be initiated into the family of DFK is a form of acknowledgement of a designer’s achievements and contributions to the industry. Naturally, expectations were high. But more on that later.

Just when one expects more or less the same from Auguste Soesastro of KRATON, he switched things up. Albeit it was so subtle that it could have been easily be missed. Auguste is a designer who prefers to strip things down to its essence and then amplify them through design. He swiftly set the message of the show with the first look: a long jacket worn over a high neck blouse with wide-leg pants and blangkon (traditional Javanese headdress), all of them in off-white colour and sans motifs.

Auguste demonstrated how elements of traditional Javanese costume can be transported into the everyday wear of a modern individual without being overburdened by the context of history and traditions. But his interpretation of the border is not limited to the old and the new. The clues lie in the next few looks. The presence of safari jacket, cape coat and three-piece suit (on male models) pointed to the theme of travel, possibly to the Wild West. Plus, his remake on the traditional man’s belt buckle brings cowboy belt to mind.

Auguste is not the type of designer to throw in a grand idea to support his collection. Instead, he built his collection from the ground up, leaves clues to support his idea while still offering enough room for the audience to interpret for themselves. The second to last look, a Grecian dress in orange gradient reminded you of the palette of a sunset as the sky dips into the horizon of the Grand Canyon. An embellished white A-line sleeveless top that glittered subtly under the spotlight from the closing look indicated a sublime starry night.

Before the start of Mel Ahyar‘s show, the screen showed a video with images of text like “social media” and “mask”. But if you are expecting the designer to open up the discourse on the virtual border and one’s sense of identity in the digital world then you’ll be sorely disappointed. It’s business as usual for Mel as she sent out pretty clothes that looked like they were transported from the fairy world. Yes, each look represents a “skin” that one adopts when they’re facing the world but without the video that served as a prologued, no one would have guessed it. Not even close.

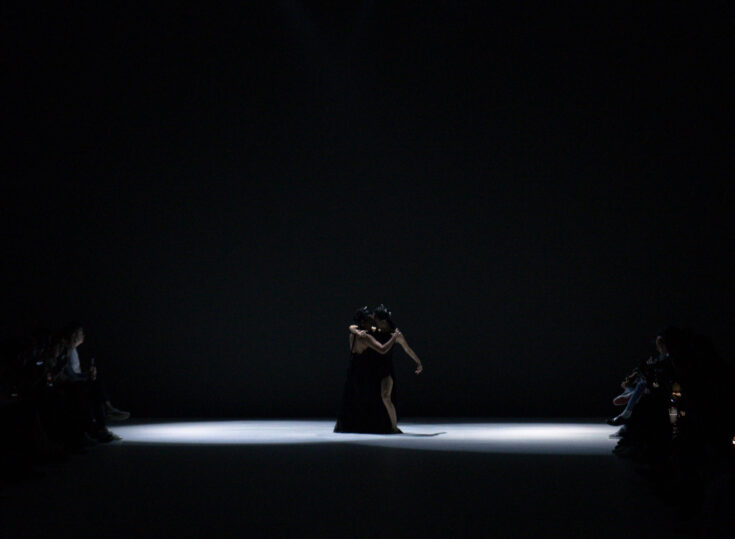

Ultimately, the collection lacked substance and barely scratched the superficial. In hindsight, her show was the most instagrammed out of the four designers. Smartphones formed an army of cyclops in the dark that followed every look as models walked down the runway in an excruciatingly slow pace. Is Mel making a point that fashion shows these days have been reduced to merely a form of entertainment? Yes, she could be. But at the end of the day, this is not an art performance.

When the dance mix music started to play during Jeffry Tan‘s show, there was this feeling that the show could very well be about the idea of bopping on the dancefloor, a connection formed from the joy of having a good time. After all, dancing is something that’s understood across different cultures around the world. Add to the fact that his creations were seen on famous celebrities, notably Kylie Minogue and Zendaya, it built anticipation for a collection imbued with Hollywood sensibilities.

But the show was so underwhelming that it’s hard to recall any standout look, if at all. The collection was lost in its own confusion. There’s a shirt with zig-zag detail on the sleeves as if it was cut with pinking shears. The description is definitely not to deride the effort because it carried a gesture of playfulness. But then there’s the long and flowy kurti-inspired tunic worn over pants. Jeffry also threw in a dash of street flair through waist bag with ruffles protruding out of the mouth, evoking a clam.

The collection was a combination of ideas that didn’t mix well. You wonder just what idea of “Borderless” that Jeffry was trying to convey. It was borderline dull. If this were to be compared to a piece of music, it’s that bland pop song on the radio that you immediately grew bored of within one listen.

At first glance, the use of ulos (traditional batak cloth) in Adrian Gan‘s show, just like Auguste’s, immediately conveyed the idea of tradition as a jumping point. But the sinister lighting and dark music suggested the border between the living and the dead. To wit, a white dress with red embroideries looked like splotches of blood from afar. And textured details of fabric in knots resemble pustules of a ghastly disease.

Adrian utilised old ulos for this collection and it was a meditation on the riches of the traditional textile. Unfortunately, as a whole, the show was too fixated on the tradition that it just felt like a restyling of ulos. Unlike Auguste’s, what Adrian presented on the runway read as costumes.

This year’s Dewi Fashion Knights is probably the most polarising to date. Outside the tent, discussion on the shows can be overheard among the guests. Some hated it, some found it okay, and the rest liked one or two looks from the show.

In a nutshell, this year’s Dewi Fashion Knights revealed the problems and the uncertainties within the country’s fashion scene. Both Auguste and Adrian tackled traditions head-on, but the latter is more likely to overshadow the former simply because it translates better through the screen despite being not necessarily wearable. Mel’s show highlighted how most Indonesian designers often lacked the ability to communicate their ideas succinctly and instead chose to stay within their comfort zone, under the cover of a pretentious concept. Then there’s Jeffry, representing a score of designers that failed to rise up to the occasion even when presented with what can be considered as arguably the biggest fashion platform in the country.