During last year’s Sotheby’s auction night in Hong Kong, a piece of artwork that parodied The Beatles album cover with characters from The Simpsons was sold for a whopping USD 14.8 million. The outlandish purchase seemed to reflect the crowd attending the auction house, as the room “got a lot hipper, with all these cool millennial buyers in hoodies,” as reported by Bloomberg after the sale event.

The artist in question was none other than Brian Donnelly – better known as KAWS – whose signature Companion characters have become some sort of a cultural phenomenon amongst the younger lot. (Remember the launch of Uniqlo x KAWS in Senayan City, Jakarta, that sold out in 30 minutes?)

Today, the thought that millennials are winning the art industry, and vice versa, doesn’t seem too far fetched. At Sotheby’s alone, millennials account for over 30 per cent of their clientele, while the same demographic became the fast-growing group of art collectors in the past year, bringing to the table a new set of channels, demands and values of how art is consumed.

In this feature, we explore how the art industry adapts to this formative shift while looking into what spellbinds these coming-of-age millennial collectors to take the plunge in art.

Online spectators

The clear mark of this shift can be seen from independent galleries brewing up online, auction events shifting digitally, and industry figures and establishments embracing social media to its full potential.

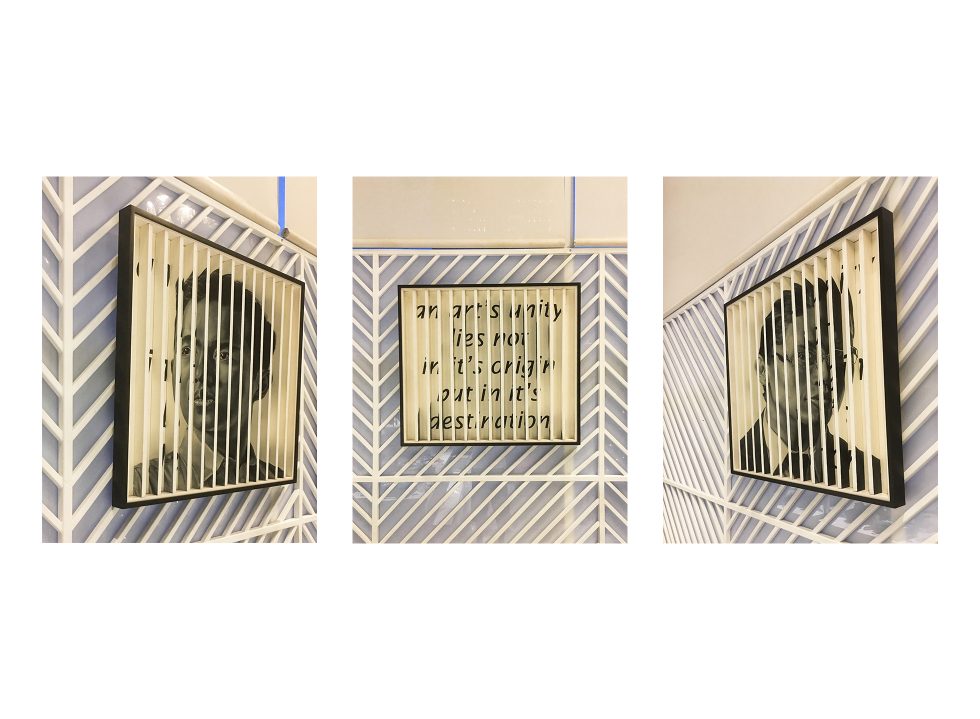

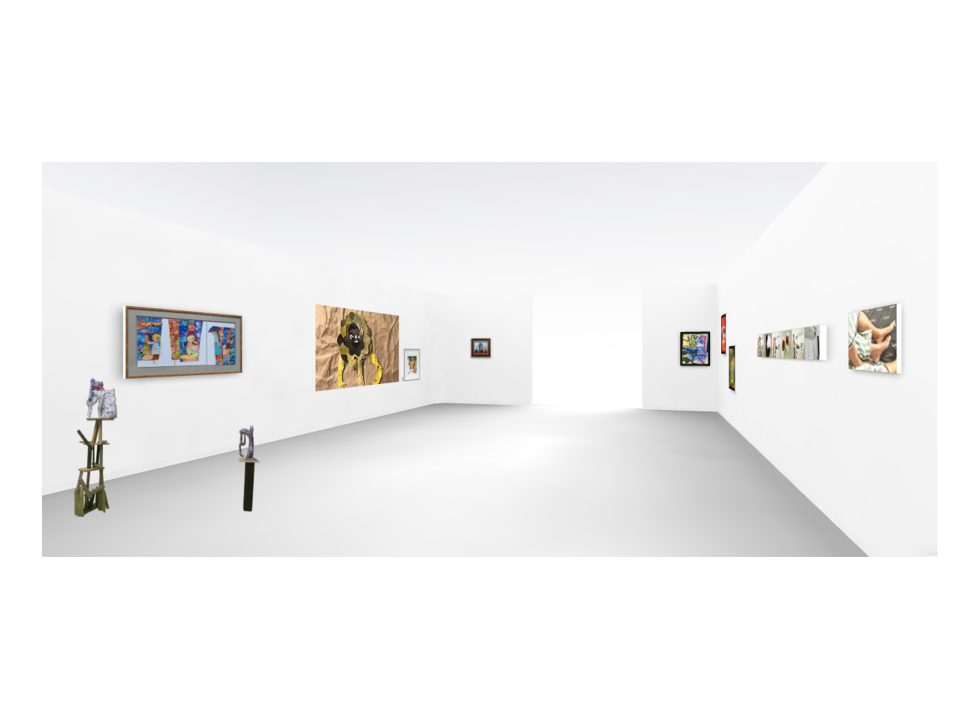

Where’s the Frame? (WTF) is one of the platforms that came out of this headway. Established this year, the online gallery was co-founded by Gianina Ivodie and Maribelle Bierens, both alumna of Central Saint Martins (CSM) in London. The team, who also offers art advisory services to seasoned and first-time collectors, operates between London and Jakarta. “At CSM, we saw fresh and exciting art all around us, but we’ve been missing a space dedicated to artists from our own generation; a place where you can discover the newest art, learn about these practices in an approachable way and collect them,” said Gianina.

Initially, WTF had planned to do pop-up exhibitions in London and Jakarta this year. Then, the pandemic put the brakes. “It made the support for our recent graduates (in London schools) even more pressing. Starting an online gallery is our way to show support to the London emerging art community entering the art scene.”

Although the team has only featured artists who studied in London so far, their upcoming first collection will consist of “a variety of visual languages, backgrounds and nationalities,” said Gianina, in anticipation.

A similar approach can be found in Cakravala, a recently-established online gallery that showcases affordable works of emerging artists. Founded by two female art enthusiasts – both 25 – who work correspondingly between Sydney and Bali, the two share roles from curatorial and editorial to marketing. The gallery’s upcoming online exhibition ‘In Her Body’, featuring Bali-based artist, Naomi Samara, marks their debut into the public.

Today, the thought that millennials are winning the art industry, and vice versa, doesn’t seem too far fetched.

Cakravala started with the founders’ own daunting experience of having to go through the opaque process of discovering art. “We wanted to buy and know more about the works of emerging Indonesian artists, but where can we do this? After Googling and searching on Instagram for hours, we’re faced with ‘email to enquire’, and we didn’t like that whole process we had to go through.” said the team.

Cakravala’s way of tackling this issue is to enforce transparency. This goes from offering clear information on price and acquisition process, down to the artists’ backgrounds, which they thought is something that the arts have been lacking when it comes targeting the younger audience.

“We have such a short attention span, so what we don’t know and understand, we won’t be interested in,” said the team. “Starting an online gallery means that we can nurture that connection between artists and audience by being as transparent as we can in all aspects.”

This kind of accessibility and interest was something that seemed closed off ten years ago, an experience that Engel Tanzil, founder of Dia.Lo.Gue Artspace can vouch for. “We opened in 2010 when everything about art, design and culture is limited. But now in Jakarta, many platforms have been created to support these interests.”

In hindsight, the art space was ahead of its time, providing a platform where cultural dialogues can happen and where local artists – from maestros to emerging talents- can take flight, even before millennials-driven-trends made ways. “At Dia.Lo.Gue, we will always support young, emerging artists. The younger generation now enjoys art and understands the values behind it. This form of support further creates sustainability in the industry.”

Where social media transcends

Diaz Parzada – whose collection includes Salvador Dalí, Agus Suwage and Damien Hirst – stumbled upon this habit at the age of 28, when his interior designer had suggested some art pieces for his newly-built home.

Diaz, now 42, has collected around 500 pieces of artworks that are decked out in his house and in the showroom of fashion designer, Wilsen Willim, where he works as a business development officer.

“One of my favourite themes is self-reflection, where I can sort of see myself in the artworks,” said Diaz. “In the showroom, there is a wall where some parts of this collection are displayed together. It’s kind of cool for me to see the likes of Picasso, Bonnet, Man Fong, and Affandi, ‘hang-out’ with Gormley, Hirst, Suwage and Hahan.”

A ‘veteran’ in the art market, Diaz has also observed the growing millennial art collectors in the sphere. From years of attending art fairs, which were almost always formal dinners, have now shifted to parties, with younger and ‘hipper’ VIP handlers managing the event.

“I think it is also because cross-sectoral collaborations between art, fashion, music and films are making the works, exhibitions, and activations more ‘accessible’ for the younger generation.” A case in point for Diaz’s younger cousin, who became a fan of American artist Daniel Arsham following his collaboration with Dior.

There’s an ethical element in the way millennials approach art, as they are more likely to prioritise stances on social and political issues, such as diversity and representation.

At the heart of these changing gears are social media, the motor behind most revolutionary ideas by millennials. In 2019, over 70 per cent (under 35) used Instagram for art-related purposes, noting the platform as to where millennials not only discover but purchase art and connect with the artists.

From the perspective of gallery owners, social media proves to be a “game-changer”, especially for the underrepresented sectors like emerging artists, women artists and minorities, noted Gianina of WTF.

“Artists have more agency in showing and selling their work. It made the experience of buying and acquiring art more accessible too,” said Gianina, where individuals at the age of 25 to 32, account for 42 per cent of WTF’s clientele. “With social media, we could learn more about what’s on-trend in any part of the world. A revolution from the conventional brick-and-mortar galleries.”

The millennial mindset

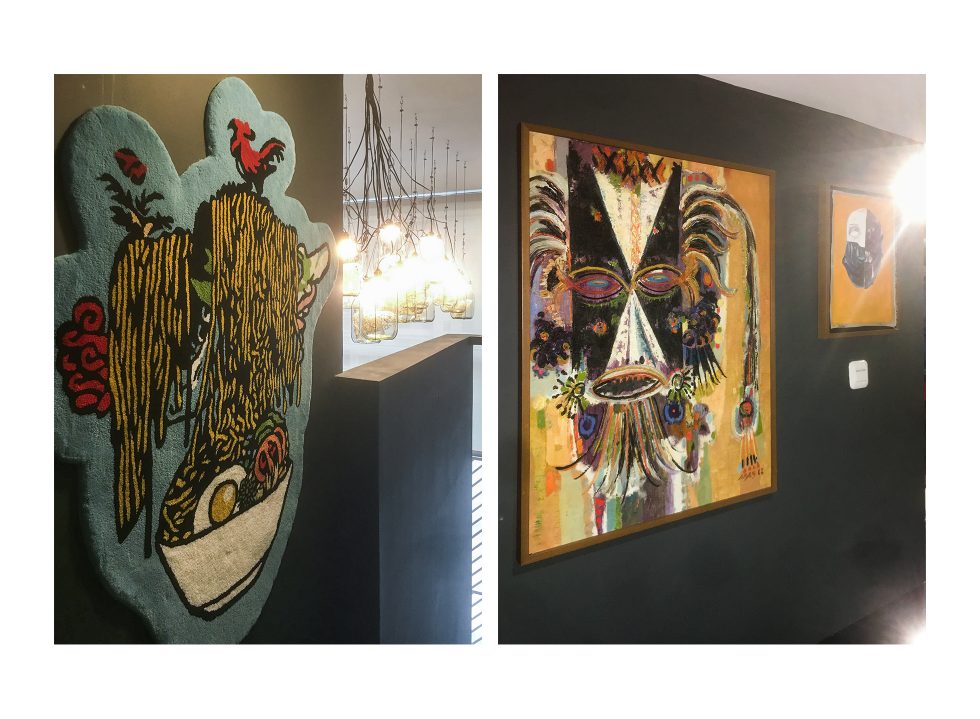

Naturally, tendencies amongst this younger generation are also different when it comes to approaching art. “Millennials are more critical; they see more, they travel more and have better access to information,” said Santy Saptari, founder of the eponymous art consulting company, based in Melbourne and Jakarta.

“They are attracted to the visual aesthetics but ideas and issues discussed in the works are considered as important. Consequently, they are more open to collect works that are not made of conventional mediums.” Santy, who set up the company in 2017, mainly works with individuals and corporate institutions in building their art collection, with services that range from advisory, exhibitions and education.

On the company’s website, Santy has also written articles about the 101 of collecting art; from how to collect on a budget to how to grow as a collector, a telling aspect of people’s gap of knowledge on the matter.

The preference for contemporary art also comes clear with the younger generation. For WTF, this is because millennial collectors and millennial artists view the world from the same lens. There’s an ethical element in the way millennials approach art, as they are more likely to prioritise stances on social and political issues, such as diversity and representation. “This doesn’t mean that millennials are exclusively interested in political art, but they are more likely to find artistic practices that resonate with their beliefs from their generation,” noted Gianina.

“Buy art that resonates with you on an immaterial level, that identifies your values and defines a part of who you are.”

From Cakravala’s observations, millennials are also far more conscious and careful in the way they spend. Due in part to their spending, which is not as much compared to the previous generation, millennials tend to go for emerging artists, as their appeal lies in that sense of relatability between each other.

“Artworks have proven a pattern when it comes to the increase of value over time, although it does depend on market trends and other dominant factors,” said the team at Cakravala. “With lower price points in the works of emerging artists, there is that sense of hope that we’ll only benefit from investing in them in the long term.”

The value: is it worth it?

The question lies in this subjectivity: why should people invest in purchasing artwork, to begin with?

Although many refer to artworks as an illiquid asset – meaning they don’t easily convert to cash – collecting art is one of the most viable investments one can make, according to Gianina. “It is something you can enjoy every day, while it increases in value over time.”

But for first-time collectors, the intimidation can shadow the intention. “You don’t have to be a collector to start investing in art,” noted Engel, who is a collector herself. “Study the art that you love. Do proper research on the artists, galleries and auction houses, and learn as much as you can. And whatever budget that you have, your collection should be focused on pieces that truly speak to you.”

For Diaz, who was one of the youngest patrons of Museum MACAN, collecting art ties back to the adventure, as he has been able to gain lifelong friends around the world because of it. But as an art consumer (the term he preferred, instead of a collector) and a strong believer in the public display of art, purchasing or donating art to museums or art institutions, makes much more sense than buying for personal collection.

“I frequently loan my collection for exhibitions. One of my joys is when a ‘replica’ of the artwork I loan, fetch quite a high result at the charity auction.” said Diaz. “I sincerely hope that I will get a chance to do more of this in the future after the economy is recovered again.”

More than rules, collecting art seems to come with its own set of values beyond financial means. For some, financial returns may bear more weight. But entailed within is also an elaborate process; from discovering the artist and connecting with their stories and values through their works down to acquiring it, which to some, can be a worthwhile and full-circle experience.

“Don’t focus on its value over time,” closed Cakravala.“Buy art that resonates with you on an immaterial level, that identifies your values and defines a part of who you are.”