This feature article on Yogyakarta is made possible through The Gateway of Java, an annual media trip supported by the Ambarrukmo Group. Throughout the trip, the MANUAL team stayed at GRAMM HOTEL (formerly Grand Ambarrukmo), PORTA by The Ambarrukmo and the Royal Ambarrukmo Yogyakarta.

—

Mbah Atemo Wiyono’s wrinkled fingers made folds and notches with a natural precision that made it seem like she was a magician. It was neither trickery nor supernatural power, but rather decades upon decades of experience doing the same pattern of movements to create a series of dolanan, traditional Javanese toys. Signature to Mbah Atemo, they are made of discarded paper.

It was a Sunday morning in late August, and the sun was making its scheduled appearance amidst the clear skies, putting a golden shine to Mbah Atemo’s vividly-hued creations. Doused in pink, green, yellow and blue using food colouring—which explained the 83-year-old’s tinted fingers—the recycled papers took the form of pinwheels, multi-layered umbrellas, bird cages on sticks and wayang dolls.

“I used to take my dolanan to Godean [market] when I was younger, and they sold really well. I walked all the way there every Kliwon (a day in the Javanese calendar system), leaving my home at 2 AM in the morning,” she said in her native Javanese. Her home, situated on the outskirts of Yogyakarta, is part of the Prancak Pandes village that brimmed with dolanan artists like her. Today, she’s the only one left.

“As we’re dealing with waste and how to manage it, Mbah Atemo here, without having to campaign about upcycling, just puts it into practice,” said local journalist Pak Kochil who acted as Mbah Atemo’s interpreter. “And she has been doing it since she was a teenager, every day without fail.”

The great-grandmother of four may have viewed her art as a way to stay closer to her parents who had taught her the craft. But her story of diligence and brand of artistry is also a showcase of the many homegrown artisans that have shaped Yogyakarta’s rich art and cultural landscape, wherein the bustling region, creative expression can manifest in various forms and thrive.

The coming together of art and communities

Best encapsulated in ARTJOG, artists both local and international gather at the annual art fair that started in 2008. Attracting rising names like Mangmoel—who established his artistic brand with an 8-metre crocheted installation at ARTJOG 2018—to seasoned, multidisciplinary figures such as Butet Kertaradjasa and Goenawan Mohamad, the fair has been referred to as the “Eid for art” in Yogyakarta.

This year’s commissioned piece by Dutch artist Mella Jaarsma set the tone for the exhibition at Jogja National Museum (JNM) with a body of work that explores themes like gentrification, identities and discrimination. In Domain I dan II (2017), costumes that look like female bodies were hung on the wall to protest laws that hinder bodily autonomy. In Rubber Time II (2003), a pair of callused feet, peeking out from a rolled-up metal sheet like a dead body, surprised visitors with the installation’s absurdity and its visceral critique of the country’s social structure.

Further into the exhibition, one would discover how the curatorial theme of motif (pattern or motive) was translated into a variety of mediums: interactive punching bags lettered with discriminating values, small crocheted legs walking on walls, tribal images made of found objects—and even young artists (ages 6-16) also offered their own perspectives at the dedicated ARTJOG Kids section with paintings, drawings and photographs. Like the artworks, the responses were similarly diverse. Couples took photos of each other, friends prompted one another to have a go at the interactive exhibits, while children cried and laughed depending on the room they were in. All around, the joy of participating in art was palpable to see.

The homegrown establishment also signals a desire to bring people closer to a sense of simplicity found in the traditions, routines and practices that the local community have done and passed down through generations.

The effects of ARTJOG are not only felt in the creative circles of the city, it has also initiated community-led projects that make way for social developments. A case in point is Warung Murakabi Minggir in Minggir Village, a traditional bulk shop that started off as an installation by artist collective Piramida Gerilya at ARTJOG 2019. Co-founders Ida Mandalawangi, Asri Saraswati, Andhika Mahardika and Suryo Seno Bimantoro then brought it to life with the help of Minggir villagers as well as those living in neighbouring areas.

Inside the Joglo-style shop are rattan crafts, handwoven tablecloths, jars of palm sugar, cassava rice, and a smorgasbord of kletikan (local snacks) that are handcrafted by the villagers using local produce in the area. A move that traces back to the essence of warung, the homegrown establishment also signals a desire to bring people closer to a sense of simplicity found in the traditions, routines and practices that the local community have done and passed down through generations—a break away from modern markets and the concerning environmental impacts of mass-produced commodities.

A spiritual streak

A similar spirit of returning to traditions and the old way of doing things can be found at Warung Bumi by Bumi Langit Institute. Located within the institute’s three-hectare complex in the region of Mangunan, where lush forests provide canopies along the winding asphalt road, many recognise it as the restaurant where Barack Obama had his lunch during a visit to Yogyakarta—but it’s a minuscule achievement compared to the philosophy that forms the foundation of the place.

“Grab a shovel and join me—are you here to learn, or are you here just to consume as tourists?” asked Tantra, son of the institute’s founder, Iskandar Waworuntu. He was digging away in a garden alongside fellow volunteers, who came to the institute hoping to learn about permaculture (permanent agriculture).

Suffice to say, he embodied the place well. Guided by Islamic philosophies, operations at Bumi Langit Institute revolve around a cultivation and farming method that follows the rhythm of nature. To achieve this, the institute had designed the mountainside complex to form a symbiosis with one another where hardly anything would go to waste. Food leftovers are spread into the chicken run to be cultivated into compost by the chickens, and the compost is then used to fertilise the gardens to grow vegetables and fruits. Even cow dung finds its use—maximising the sloping terrain, a sewer system directs the waste straight into a processing well that turns it into biogas to fuel the stoves at the main house’s kitchen.

The direct result of this system can be seen through the menu at Warung Bumi; from the homemade sourdough bread and jam appetiser to the koro beans tempeh and butterfly pea kombucha, each one utilised ingredients that are harvested from the institute’s gardens. “With the consumptive and destructive lifestyle of the city, somebody has to counterbalance it and care for the environment. That’s what we’re doing here. Nurture and nature go hand in hand—to nurture yourself, you need to be in touch with nature,” stated Tantra.

Pilgrims make it their destination—whether to visit the seaside Hindu temple Pura Segara Wukir or to meditate at selected spots across the rocky seafront.

This connection to nature is also prominent in the seaside village of Kanigoro in Gunungkidul. Children’s kites fly high amidst the billowing sea wind, schoolgirls play football on a beach cradled between rock formations, and fishermen, navigating the clear waters upon matching blue boats, bring home a bounty of fresh seafood that attracts culinary hunters into the area.

Ancestral myths and beliefs still guide the villagers in navigating their day-to-day lives. Every 1 Sura (the first day of the year based on the Javanese calendar system), these villagers would gather on the beach for the ceremony of Labuhan. They collect harvests from both the earth and the sea—including rice, fruits and fish—place them on decorated boats, and cast them off into the ocean as offerings of gratitude to Kanjeng Ratu Kidul, the mythical queen of the southern seas and divine spouse to the sultans of Yogyakarta Sultanate. Her legend—as the guardian of the sea, controller of the wind and protector of the fishermen—is so embedded into Javanese culture that she’s not only present in the Javanese religious tradition of Kejawen but also in the region’s Hinduism and Islamic dogma, with each belief having their own perspective to what and who she is.

On the edge of the village, the hilly landscape meets the sea once more at Ngobaran Beach. Legends have it that it’s here where the last emperor of the Majapahit Empire met his demise through self-immolation. The tale is often contested, but it doesn’t take away from the sacredness of the place. Pilgrims make it their destination—whether to visit the seaside Hindu temple Pura Segara Wukir or to meditate at selected spots across the rocky seafront. That seems to include the royals too.

“Sultan [Hamengku Buwono X] does his meditations here,” said the sultanate’s abdi dalem (palace retainer) Pak Darto, pointing at a man-made stone structure on the edge of a sea-facing low cliff. “It’s how he seeks enlightenment to help him with his rule.”

A gander into royal life and traditions

Until today, royal customs and families are still being revered in the region with the Sultan acting as its governor and Prince Paku Alam X of the Pakualaman Principality as his deputy.

Formed in 1813, the Pakualaman dynasty began as a political contract between Prince Notokusumo, son of Sultan Hamengku Buwono I, and the British government, following a period of conflict between the sultanate and the short-ruling colonial power that climaxed with the Geger Sepehi battle at the Keraton (royal palace). Trusted with his own territory for his service during the battle, Notokusumo was crowned Pangeran Merdiko (independent prince) with the title of Prince Paku Alam I.

Today, his palace Pura Pakualaman remains standing at the heart of Yogyakarta amidst urban developments that surround it on all sides, facing the south in respect of the Keraton that sits nearby. “Engeta Angga Pribadi,” reads a Javanese inscription at the entrance, which hangs by a full-sized mirror. “Before entering the realm of knowledge, one must first be self-aware.”

The two-century-old ivory palace easily impresses with its manicured gardens, and well-maintained halls as well as its fusion of Javanese, Dutch and Middle Eastern architecture—but it’s the Paku Alams’ affinity for knowledge and education that continues to sustain their legacy and attract visitors to their palace.

“Our country’s father of education, Ki Hajar Dewantara, was the grandson of Paku Alam III. The early Pakualaman princes were mostly concerned with internal matters, but when he built the Taman Siswa school, that changed the public’s perception of us,” shared an abdi dalem guide, Ki Surokso Kadar. “Then Paku Alam V encouraged all his descendants to study as much as possible and use their education to better the lives of their subjects. That’s why the country’s first indigenous doctor, engineer and lawyer all come from Pakualaman,” he went on to claim.

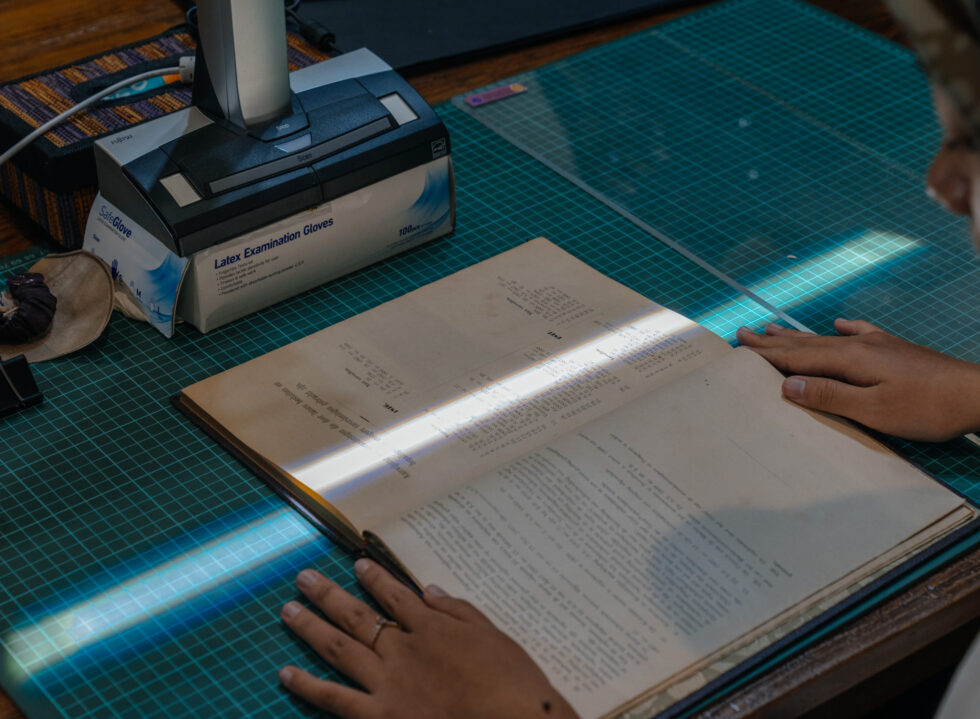

On the west wing of Pura Pakualaman, multiple rooms are dedicated to storing the palace’s archives for scholars to study. Volumes of books written in various languages provide documentation of the country’s pre-independence history; Javanese scriptures narrate the happenings with an indigenous perspective, and photographs from the early 20th century, amassed from the princes’ personal collections, offer a glimpse into the architecture and life of the palace during the era.

Time-honoured rules guide the execution of the ceremony, and a deeper meaning is imbued within each element.

In a similar manner, guests of the Royal Ambarrukmo Hotel also have the privilege to partake in the royal traditions that have been preserved across generations of Yogyakarta sultans. The hotel that opened in 1966 is built on the grounds of the Kedaton Ambarrukmo palace, the former home of Sultan Hamengku Buwono VII, which gives it another layer of intimacy and connection to the experience.

One of the highlights is Patehan, a royal high tea ceremony that can be traced back to the late Sultan’s rule during the turn of the 20th century. It was then that tea culture took on a new significance at Keraton with the establishment of a dedicated wing as well as a staffing team that has a specific purpose of serving tea to the Sultan, his family and guesting dignitaries. The one at Ambarrukmo is a loyal adaptation of the procession.

Time-honoured rules guide the execution of the ceremony, and a deeper meaning is imbued within each element. The mandatory sashes called samir, worn by the hotel staff that fill the roles of abdi dalem, are a signifier of royal duty. The copper teapot used to heat up the water is believed to have purifying properties and can ward off misfortunes. And while it might have come off as merely a photo op for the tourists, traditional Javanese attire is made obligatory among those who partake as a way to maintain the sanctity of the tradition.

The precision with which the ceremony is carried out, stretching to details such as the temperature of the tea and the prohibition of stirring while brewing (to maintain its flavour), speaks to Yogyakarta’s ability to transform the simple act of serving refreshments into a mindful practice that is layered with intention and passed-down values. This notion also resonates with the practice of Jemparingan, a traditional form of Javanese archery that one could try as well at Ambarrukmo.

Under the hands of the Yogyakarta Sultanate and the Pakualaman Principality, the Mataram-era sport is more than just a tool of war or an expression of violence. Rather, it’s a practice on ‘knightly’ characters that the first Sultan Hamengku Buwono expected from his subjects: sawiji, greget, sengguh, ora mingkuh or concentration, high spirits, humble confidence and accountability—and it’s easy to see how each of these characters translates into the seemingly simple act of shooting arrows.

For one, sitting cross-legged (while wearing a batik cloth at that) demands the archer to maintain focus on their posture and the target as they pull the string. The small cylindrical target seals the challenging nature of the sport, and only those willing to try and try again can eventually get the satisfaction of hearing the bell ring when the arrow lands.

Today, both royal traditions are still practised regularly. At 6 and 11 AM on the dot, visitors at the Keraton can have a glimpse of serving ladies carrying trays of tea and a combination of sweet and savoury accompaniments for the Patehan ceremony—even when the Sultan is not around. Meanwhile, every anniversary at Pura Pakualaman is celebrated with a Jemparingan competition known as the Paku Alam Cup, which could see more than 500 archers trying to outdo one another for the coveted cup and cash prize.

A meditation on the city

In downtown Yogyakarta, one could observe the past and present coexisting with ease. Centuries-old forts that circle the Keraton sit casually with houses, printing shops and a viral ice cream franchise. Becak (cycle rickshaws), both motorised and otherwise, remain a popular mode of transportation alongside online ride-hailing services. While cars pass through small gates that were initially meant to fit horse-pulled chariots and pedestrians.

Offering a sense of meditative reflection of one of Indonesia’s oldest cities, roaming through Yogyakarta is like seeing remnants of history sustained and moulded to fit the changing of times—all without losing its essence. A case in point, its spatial design known as the Cosmological Axis of Yogyakarta was recently awarded with a world heritage status by UNESCO. Designed by Sultan Hamengku Buwono I himself, his philosophical leaning means that details down to the use of sand instead of grass at the alun-alun (town square)—which cools down at night and grows hot under the sun, a metaphor for the world’s opposing duality—carries meanings trough symbolisms that are still preserved to this day.

Indeed, whether one spends a short or a long-term stay in Yogyakarta, it doesn’t take long to sense the region’s inclination for spirituality, communality and respect for traditions permeating through aspects such as art, culinary and culture alike. It’s a character that continues to bring people together within its borders—each one seeking their own thing. Like the “Engeta Angga Pribadi” mirror that hangs upon the entrance of Pura Pakualaman, Yogyakarta continues to find ways to evoke the spirit of the region by looking inward.