Back in November last year, Andi Rahmat of Bandung-based design studio Nusae flew to Tokyo, Japan to receive the prestigious Good Design Award for the city branding initiative Menuju Tubaba. He was accompanied by Tulang Bawang Barat’s former head regent, Umar Ahmad, who during the award ceremony had proudly donned a traditional Lampung attire: the handwoven tumpal fabric sarong and the kikat manuk meghem, a headpiece of the same fabric that is inspired by the form of a roosting chicken.

Andi and his design studio Nusae are a part of Menuju Tubaba’s notable crew of architects, urban planners and designers gathered by Pak Umar to realise his transformational vision for Tulang Bawang Barat with architect Andra Matin at the helm.

“At first, we were caught off guard by the immensity of Pak Umar’s vision. It was also our first time doing something of this scale,” recalled Andi, the founder and principal designer of Nusae. “He didn’t give us a specific brief. Instead, he told us stories about Tulang Bawang Barat, noting that it is a place of equality and balance, anchored by ecology and culture. Then, he invited us to visit and experience it for ourselves.”

“My approach is creating a Tubaba that is modern but still grounded in its Lampung roots.” Andra Matin, lead architect of Menuju Tubaba.

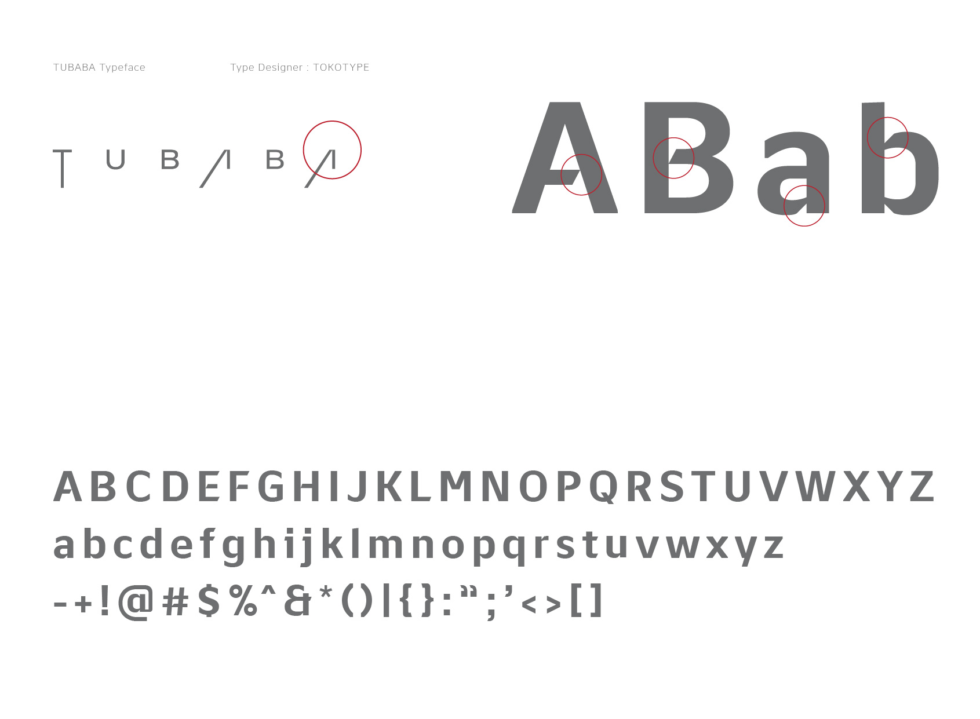

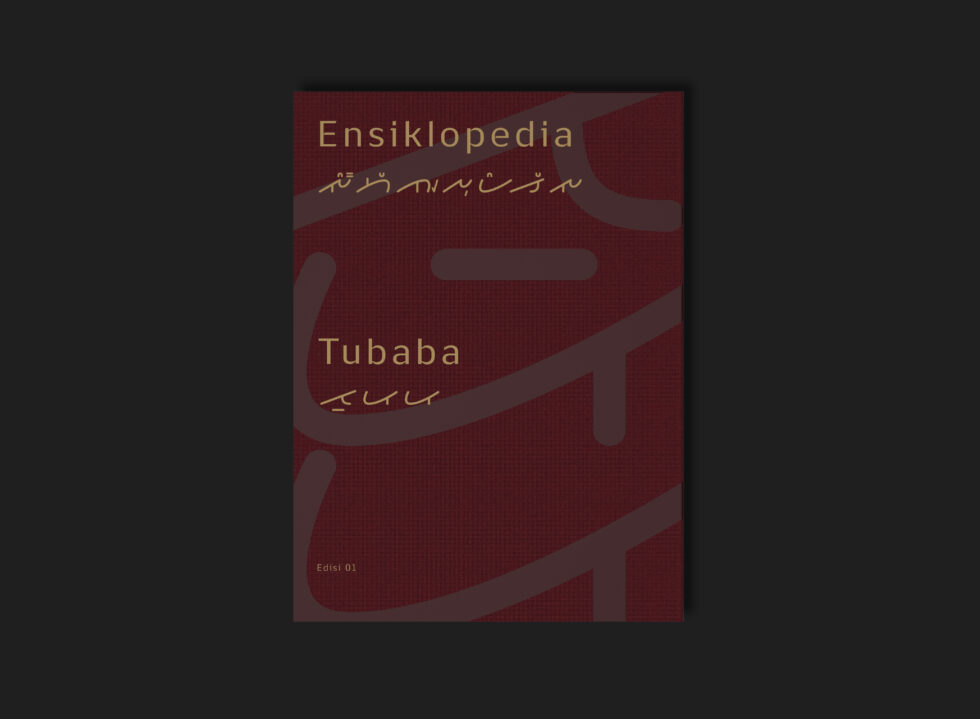

Tasked to design and strategise for Tubaba’s visual branding and communications, Nusae collaborated with the Jakarta-based type foundry company Tokotype to design Tubaba’s city logo and typeface, which is translated into the city’s environmental design as well as a lineup of Tubaba merchandise that features t-shirts and scarves to city maps. Most recently, they collaborated with Italian shoe brand Superga to release exclusive Tubaba merchandise in the form of the brand’s classic canvas and rubber-soled footwear.

The visual identity of Tubaba is slowly coming together. But if there’s one identifying landmark that has served as a design template since the beginning, and has been designated as the main icon of Tubaba, it’s the Islamic Center by Andra Matin.

The merging of past and present

“I remembered Pak Umar saying, ‘Tubaba needs to go from bukan-bukan (ordinary) to bukan main (extraordinary)’,” recounted Andra Matin of his conversation with the former head district during the early stages of Menuju Tubaba. “I was quite challenged by that.”

That challenge transpired in the Islamic Center, the first landmark built under the project that comprised the As Sobur Mosque and Sessat Agung cultural centre. “My approach is creating a Tubaba that is modern but still grounded in its Lampung roots. But as a whole, the direction we’re taking is designing something that is beautiful and healthy for people here to experience,” explained the architect at his home in Bintaro.

Following the Islamic Center, the same design philosophy was also applied to Tubaba’s cultural institutions like Pasar Pulung Kencana and Masjid Muttaqin, also designed by the Aga Khan Award-winning architect.

Just off the main street of Raya Pulung Kencana, the traditional wet market of Pasar Pulung Kencana was transformed into a massive and open-air, two-story building. Refurbished to shelter over 400 stalls, from fruit and vegetable vendors to booths selling jajanan pasar and basic home needs, the market’s new design is clean and minimalist, defined by the raw and cool quality of concrete, and the intricate weaving facade that frames the building. The latter was handcrafted by BYO Living, a Jakarta-based architecture weaving design firm, to function as the building’s cooling system, as well as to add a traditional charm to the market.

Following the Islamic Center, the same design philosophy was also applied to Tubaba’s cultural institutions like Pasar Pulung Kencana and Masjid Muttaqin.

In the late afternoon, when the crowd is not as busy compared to the morning, soft light filters through the patterned facade and the roofless structure down to the patch of greenery in the centre of the market. Around it, vendors on spread-out mats sit cross-legged, exchanging friendly banter while peeling bulbs of garlic and shallots.

“Before, the market was stuffy, dark and muddy. Now, every element is a complete contrast from that. The reason why I built the garden in the middle is so that it could brighten up the space and fuse more with nature,” said Andra Matin.

Concrete finds its way again in Masjid Muttaqin, also known as Masjid Tepi Sungai (Riverside Mosque), which is situated deep inside Karta village approximately 20 minutes away from the city centre. Settling quietly amongst residents’ homes, the house of worship sits like a modern gallery from the outside with its exposed concrete and wooden fixtures. Seamlessly integrating with the natural elements around the village, Masjid Muttaqin departs from the conventional designs of sacred spaces that most people are already familiar with.

“The design is very contextual with the river and I want to introduce the idea that a place of worship doesn’t always have to be traditional,” commented the architect. “The most important thing is once you enter, silence and calmness fill the room. In the end, we as humans want to feel something bigger and more beautiful—this experience of space is what I want to show through the design.”

The physical and non-physical value

When Andi first arrived in Tulang Bawang Barat in 2014, he came with the intention of fully grasping what Pak Umar had told him about the regency during their first meeting in Jakarta. At first, he only saw an area similar to other Indonesian districts, but after delving more into the place’s history and witnessing the relationship between Pak Umar and the locals, he realised that Tubaba holds a different future.

“Tubaba does not have mountains and seas. In this regard, Pak Umar expressed that the uniqueness that can draw people to visit Tubaba must be created by humans. That’s why it’s very important that we present an urban design that feels comprehensive, both physically and non-physically.”

The process was long, and it’s still ongoing. Seeing the need to solidify Tubaba’s identity beyond landmarks and structures, Andi consulted with the three individuals that have been involved with the project since the beginning, like Andra Matin, Hanafi of Studiohanafi who helps curates Tubaba’s art programmes, and fashion designer Auguste Soesastro who develops the designs for Tubaba’s official traditional wear.

“The quality that we wanted to maintain through this project is creating a design that is easy to understand, one that is able to merge the old and new values of Tubaba.” Andi Rahmat of Nusae.

“We also had many talks with several parties from the local community, where we learned about the values of life in Tubaba, such as nenemo (nemen nedes nerimo), which means hard-working, tenacious and sincere—they are qualities that reflect the people of Tubaba,” said Andi as he looked for insights that he can translate to his designs.

One of the first manifestations is Tubaba’s logotype, which features an elongated ‘T’ and ‘A’ in sans serif. The stretch signifies how everything is rooted in the regency’s history and local traditions, while the ‘A’s are shaped to resemble an arrow, illustrating Tubaba’s forward-thinking approach and vision of “pulang ke masa depan” (returning home to the future). The red and gold palette is also a nod to the traditional Lampung attire and the region’s various cultural elements.

“We want this specially-designed logo and font to be used across sectors, from government necessities to the Tubaba community itself,” noted Andi.

All hands on deck

In the journey to build the new Tubaba, Pak Umar firmly believes that they could not move alone. From here, the gathering of minds slowly expanded to welcome collaborators from various disciplines.

In addition to the aforementioned figures, Nusae has collaborated with multidisciplinary artist Jordan Marzuki to produce a visual documentary that encapsulates the vision, cultural programmes and creative process behind the project. The naming and campaign of Menuju Tubaba itself were also conceived with the help of Jakarta-based research company Nation Insights, who helped with research and strategised ways to communicate Tubaba’s stories and vision in a narrative manner.

“All these dialogues and exchange of ideas have birthed a harmonious collaboration across disciplines, and it has helped us design various communication strategies that are well-rounded and holistic.”

Most importantly, Andi hopes that he is able to convey a design is that functional yet distinct in character, one that is filled with values that capture the roots and hopes for Tubaba. “The quality that we wanted to maintain through this project is creating a design that is easy to understand, one that is able to merge the old and new values of Tubaba. Only then can these designs fully represent Tubaba.”

Stay tuned for the final part of this series, where we will dive further into the development of the cultural and art programme, as well as the project’s impact on the future generation. Head to our first article to read about Menuju Tubaba’s founding vision and the key collaborators that helped shape it.