Food writer Kevindra Prianto Soemantri was in high school when he first made and sold American classic chocolate chip cookies to his classmates. They were crowd-pullers.

At the time, his daily routine consisted of shopping for supplies at Titan Baking in Fatmawati after school and making the orders as soon as he reached home. His affinity for food also traced back to when he was a child hanging around in the kitchen of Cafe Blend, his late father’s restaurant, at Kafe Tenda Semanggi.

“I think food has always been in my blood because of these early experiences,” says Kevindra. “When I decided to focus on food and got full support from my parents, the rest is history.”

MasterChef Indonesia 2011 was his leeway into the scene, where he became the youngest contestant to compete in the televised cooking show. Going so far as Top 10, Kevindra’s elimination didn’t cower him from bouncing back to the field as he continued his hustle to Bvlgari Resort Bali, where he gained kitchen experience at Il Ristorante – Luca Fantin.

Today, however, Kevindra is best known for his words. Or perhaps, that guy in Netflix’s 2019 “Street Food: Asia” docuseries, where he talks about Yogyakarta’s local fares on Episode 4. But his foray into journalism started years back in late 2014, working in publications like Kokiku TV, Kenduri Indonesia, Traveloka Eats! and The Jakarta Post as food editor and columnist.

The twenty-seven-year-old keeps himself busy by co-running an online food publication, Feastin’, all the while writing his own books. His non-stop grit, evident through what he’s achieved so far, leads us here today at the dawn of his fifth book, “The Art of Restaurant Review” which will be out this month.

“This book is meant for our friends in the media industry or anyone outside the circle, to guide them with the proper standard when writing about food and restaurants.”

I get to meet Kevindra one afternoon at his cousin’s residence in Pondok Indah. Wearing a casual, all-black attire, he warmly greets me, already with a sanitiser spray ready in his grip. “I’m sorry, I have to do this every time now,” he says as we laugh at the ‘new normal’ decorum.

“Who knew Batavia was so French? We were already so ahead [of our time] back then.”

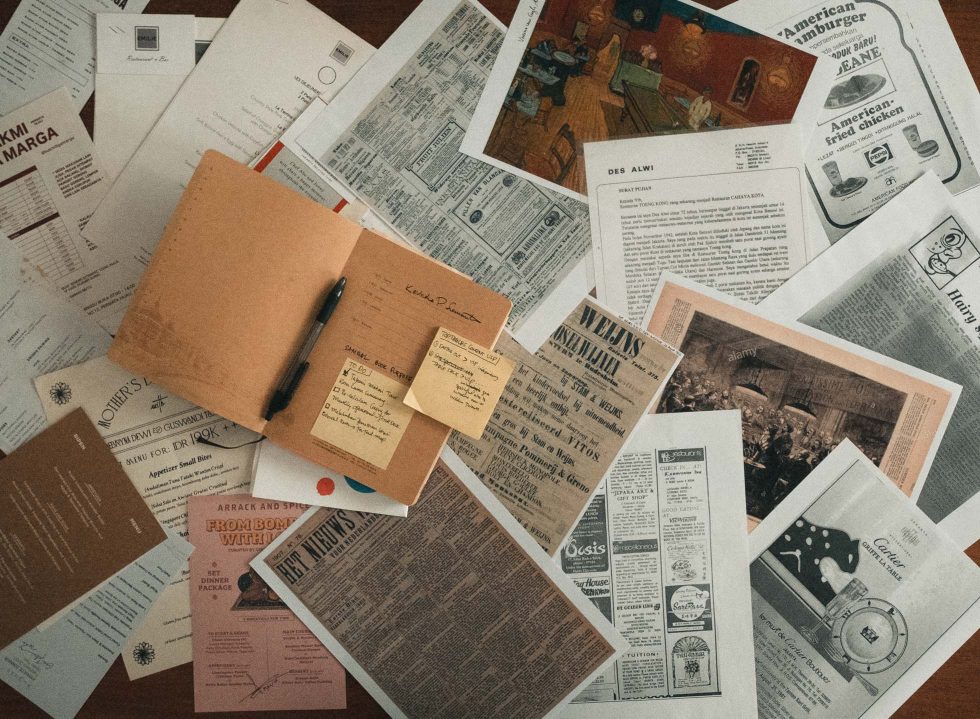

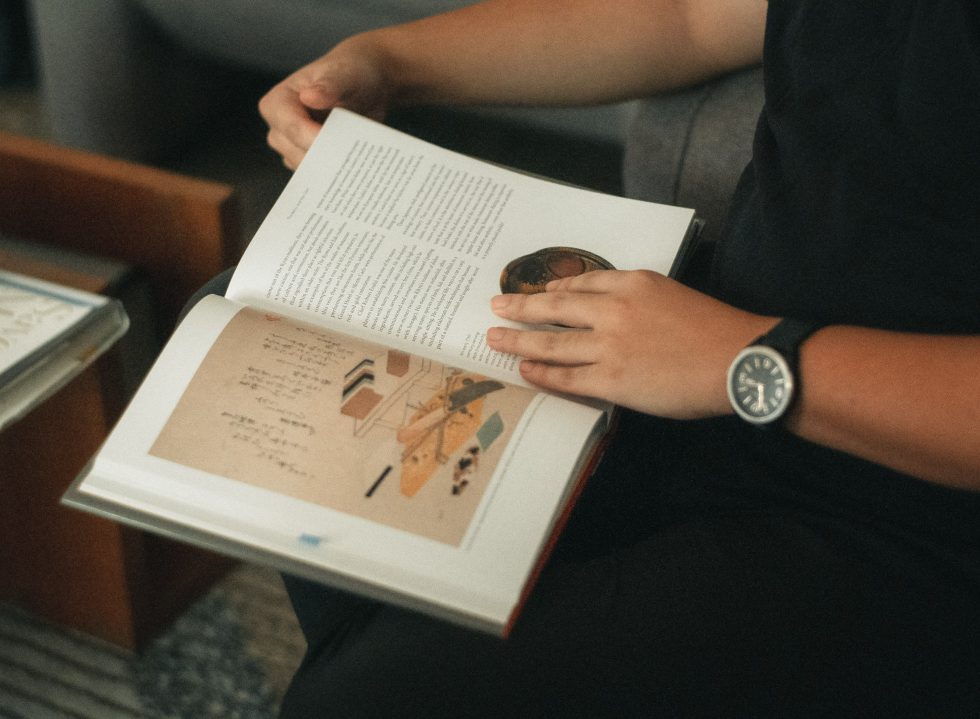

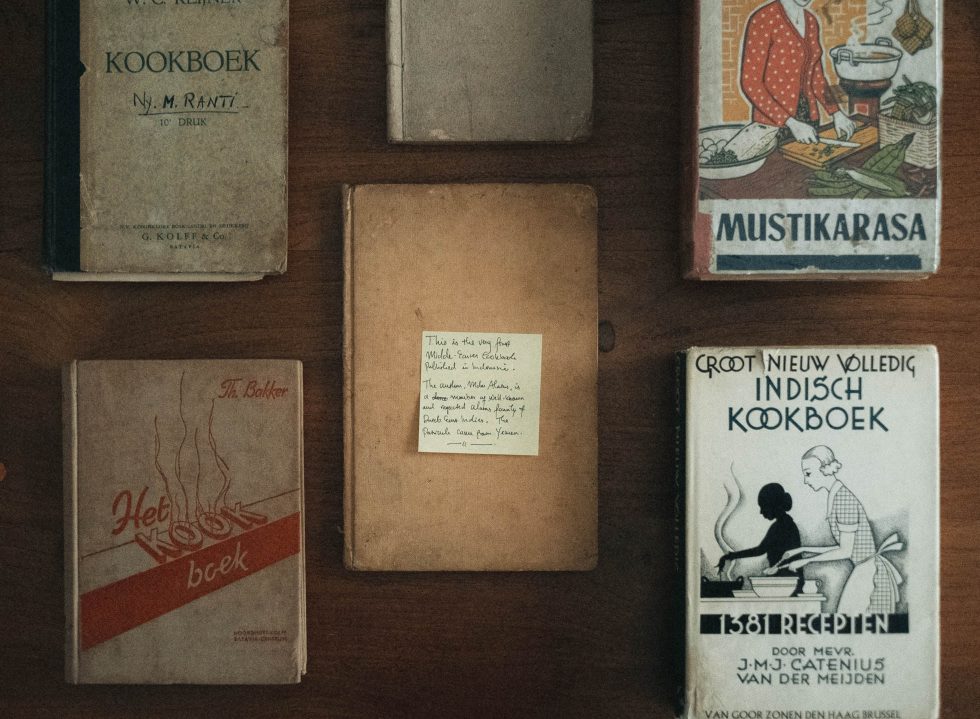

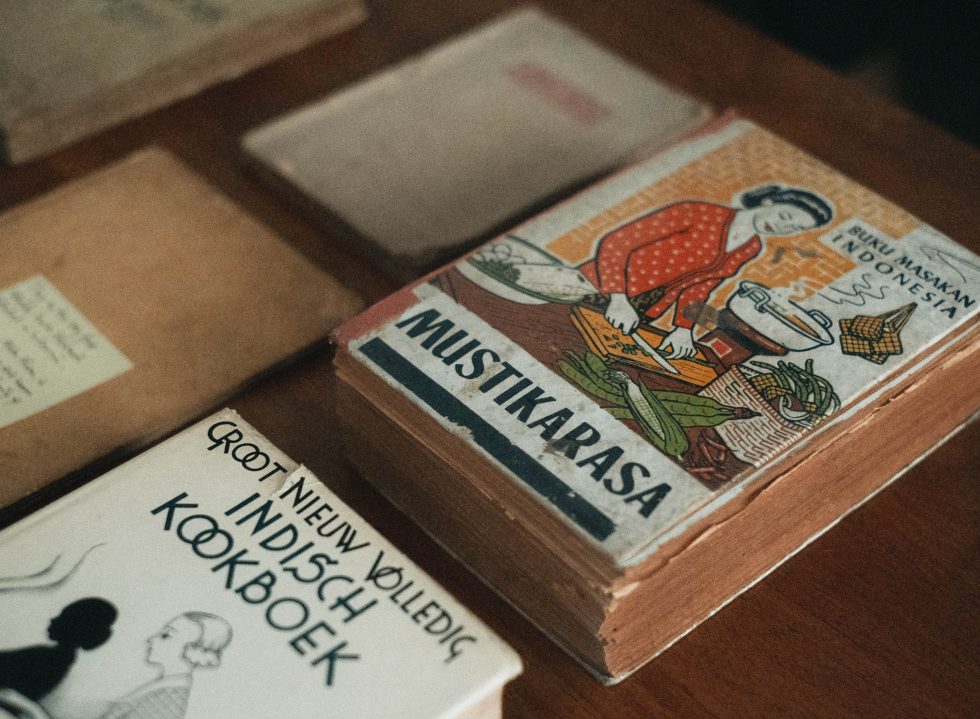

He then leads me to the living room, where he right away shows off his collection of books and archives that he gathers for his work and personal research. From old newspaper clippings of the food section neatly filed in folders, a stack of restaurant menus that Kevindra has collected throughout his visits, to perfectly sealed vintage cookbooks, this collection will impress even the indifferent.

In this mix, you’ll find a trove of fascinating findings that record the city’s taints of food and restaurants, dating back from the 1800s to 2000. From spending hours at the national library, scouring Tokopedia to befriending a vintage bookshop owner at Blok M Square, Kevindra always finds a way to get his hands on these relics.

As Kevindra narrates his unearthings, an impromptu history lesson becomes inevitable: “Did you know that Batavia already had an estaminet (a French cafe) back in 1846 in Noordwijk (today’s Jalan Juanda)?” to “Did you know that one of Sukarno’s early initiatives during his presidency was creating a nation’s cookbook?”

Kevindra continues with the same fervour throughout. “This is from 1902, a French cafe/restaurant in Noordwijk,” says Kevindra, as he hands me a print out copy of the establishment’s menu. “See what they were selling back then: Moët & Chandon, Russian caviar, foie gras. Who knew Batavia was so French? We were already so ahead [of our time] back then.”

Learning about the good old days may not carry the same spell for those who don’t share the same appreciation for food. But for Kevindra, these are further revelations that Jakarta – or Batavia at the time – was already lavish with dining concepts that are booming today.

“Back then, [food media] here was very… hypocritical, I’d say? One wants to please the others, and vice versa.”

“As a writer, it is my job to make people aware of the city’s identity,” says Kevindra. “All this research further proves that Jakarta is a legit dining city, and it’s up to the industry’s players to make something out of it. We already have a strong foundation going back to the 19th century. Not every city has this privilege.”

When Kevindra started writing in late 2014, the local food media was either scant or frustratingly stale. The lack of voice in the industry eventually spurred him to try and make his mark.

“Back then, [food media] here was very… hypocritical, I’d say? One wants to please the others, and vice versa.” says Kevindra, seemingly careful with his words but pulls no punches nevertheless. “I also saw a void in food writing. Our food is ample and diverse, with a melting pot of influences from other countries. At the time, I thought why did we still not have a dedicated food media here? The industry is already big, but the media pale in comparison.”

With today’s crop of writers and spectators seeking more quality content and stories that speak volume, food writing has become more prevalent. “I’m beginning to see a strong interest in food writing from people all over the country,” notes Kevindra. “I recently held two virtual classes on food writing and I was surprised to see half of the participants came from Malang, Bandung, Medan.”

Kevindra also credits Laksmi Pamuntjak’s “Aruna dan Lidahnya” and Fadly Rahman’s “Jejak Rasa Nusantara” for their cultural impacts on the local food media.

At the same time, Kevindra notes the role of food bloggers, influencers and content creators, in shifting the way people consume food and restaurants they go to. Does he see them as competitors? Not at all. In fact, he acknowledges that “they have an influential power to move people.”

The question is, are they doing it properly? This is the ground covered in Kevindra’s upcoming “The Art of Restaurant Review”. In his honest opinion, the “Jakarta Good Food Guide” (2001) by Laksmi Pamuntjak, was the last proper review writing about Jakarta gastronomy. Since then, he feels that nothing has been quite like it.

“We already have a strong foundation going back to the 19th century. Not every city has this privilege.”

Research for this upcoming book ranged from gathering journal papers, like “Writing For Food” by food journalist Pauliina Sinauer, to studying restaurant reviews from the likes of The New York Times.

“All these gatherings translate to a list of formulas that explore how we should understand and write about taste and characters of food, along with different kinds of cuisine and restaurants.” Written in a light, casual format, “The Art of Restaurant Review” is meant to be approachable for all. As Kevindra would say, “food is fun, so the approach should be too.”

But his book can only do so much to fill the gap, and others in the industry must also find ways to enrich the food media, starting from how food should be written and diversify its scope.

“I believe countries with a progressive food industry have an equally progressive food media. Take the U.S. and Europe, they have proper critics and stories that go beyond recipes and reviews,” notes Kevindra. “It’s because they have a serious approach to food journalism.”

I ask if this is what our media lacks, especially for aspiring writers who want to write about food. “Unfortunately, there are not many focused platforms for [serious writers] here, so our industry needs to see this growing potential in the future.”

As the better half of Feastin’, Kevindra also sees this as his own homework to give opportunities, as well as groom the new generation of food writers.

“My grand plan for [Feastin’] is to add various sections for content. I imagine there’ll be one section for restaurants and drinks, one for culture, one for recipes and one for food analysis and trends,” he continues. “Therefore, it’s important to have specialised writers for each section. Today, contents are also very holistic, so that’s another homework.”

“I believe countries with a progressive food industry have an equally progressive food media”

Everything Kevindra has done always seemed ambitious, but after spending a long afternoon with him, all this doesn’t seem surprising. Maybe it’s because of his vast and articulate knowledge of the city, or because he goes beyond the bare minimum for his research. Maybe because his love for food and desire to improve the industry is not only genuine but commendable.

Last week was the first time since the pandemic struck that Kevindra visited and reviewed a restaurant with safety and health measures in place. Kevindra, who also assisted in the making of the government’s updated protocols, delights in the feeling of returning to his world again.

“I was bemused by the situation,” he says, laughing. “Because it seems like we don’t appreciate the things we do every day, so we get to appreciate them even more now. I made sure I savoured every moment [at the restaurant].”

Of course, he asked for a copy of the menu. He wrote on it ‘the first restaurant I visited after COVID-19’. Under the current climate, this simple note seems to hold more meaning than ever.