As a food writer, Kevindra Soemantri is decorated in experiences that spotlight Indonesia’s culinary wealth. But when talking about the legacy of food and food matters in Indonesian history, the topic of restaurants doesn’t surface up as often with no good reason for this unexplainable void. In his latest book, Jakarta: A Dining History, Kevindra fills this gap by chronicling the history of dining in Jakarta since 1890, an era filled with opulent palace hotels and chic European cafes, until the 1990s where dining defined a Jakartan’s modern lifestyle.

In this interview, Kevindra shares the experience and the running thoughts after exploring 200 years of lifestyle history in Jakarta, as well as his hopes for a better, more robust restaurant industry in the hands of the youth.

MJ: What prompted your curiosity to embark on writing a book about the history of dining in Jakarta?

KS: Growing up, restaurants were a big part of my life. My father owned one, my grandparents are foodies who loved to eat out, I was in culinary school and worked in Bulgari Restaurant in Bali, too. So restaurants are my familiar surrounding. When I dived into food writing, I realised the missing literature about our dining scene in Jakarta. Which felt ironic because that’s not how I or my family and friends experienced the liveliness of restaurants; all the stories people share about old restaurants in the city were nowhere to be found. So this curiosity stirred my motivation, intrigued me to uncover more about the culinary scene with restaurants being important institutions in a city’s society.

MJ: What was your first lead on a project that ambitious?

KS: I owe the first pieces of this puzzle to the late Bondan Winarno (Indonesian food journalist and writer), with whom I met at Ubud Writer’s Festival in 2018. We exchanged ideas and it turns out we had similar thoughts about restaurants and non-existent documentation of the scene. In a letter he wrote me, he guided me through the first steps of my research, but it was up to me to find the rest of the pieces.

MJ: And how did you end up finishing a “puzzle” that spans 200 years of Jakarta’s dining history?

KS: That 200-year timeline really happened naturally. To be quite frank, I intended to cover the history from the 1970s, thinking that it was the birth of Jakarta’s dining scene. But the more digging I did, the older stories were more fascinating. And that’s what I love about writing, it’s the process and discovery along the way.

MJ: What was the most fascinating discovery?

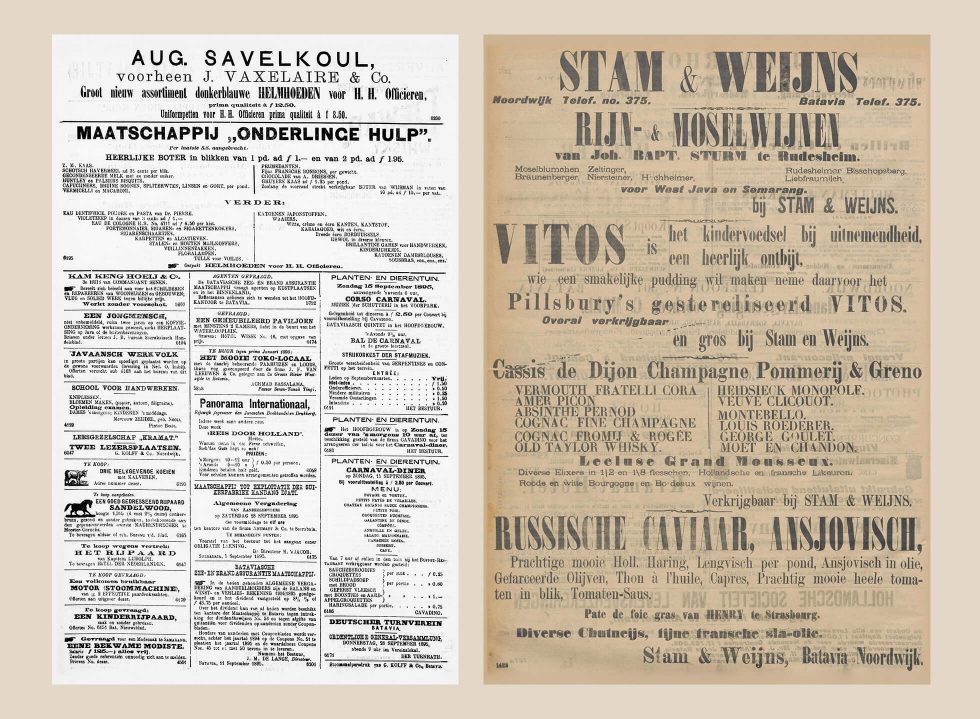

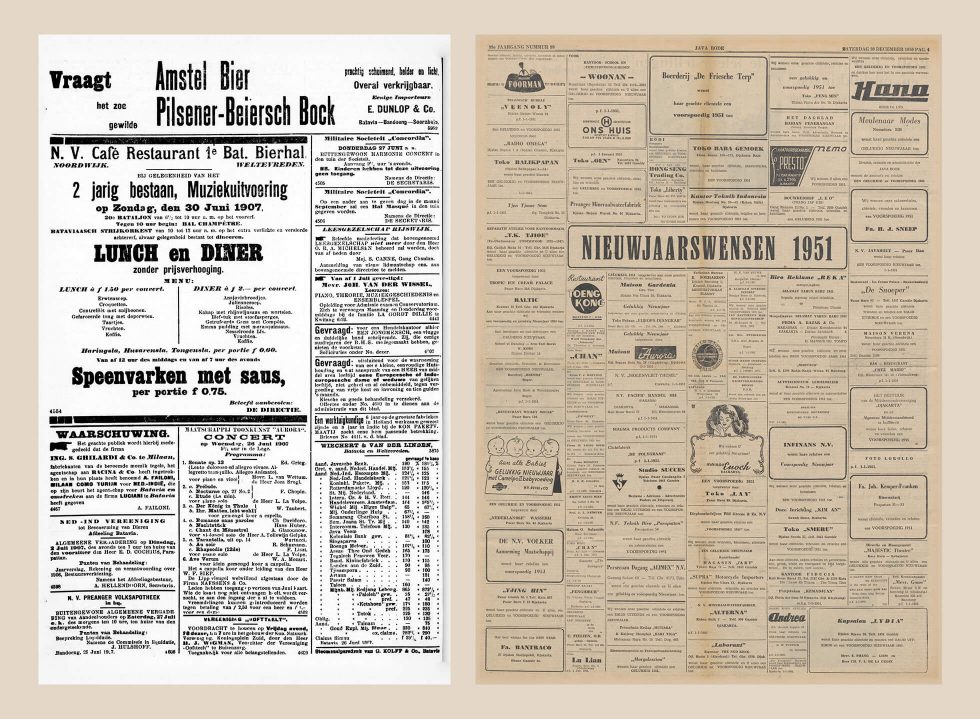

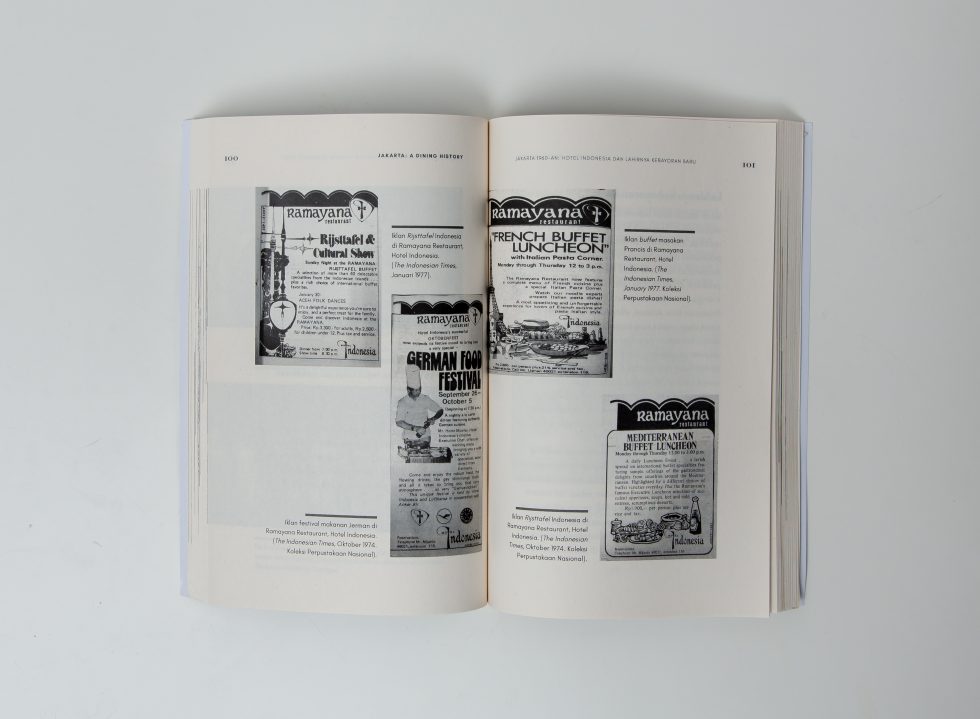

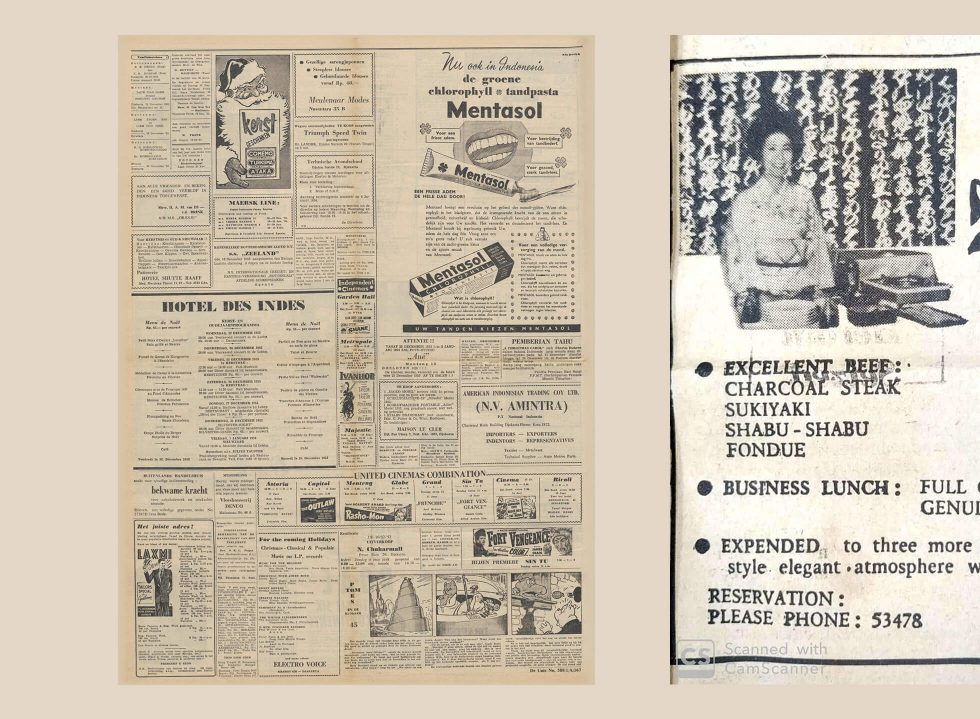

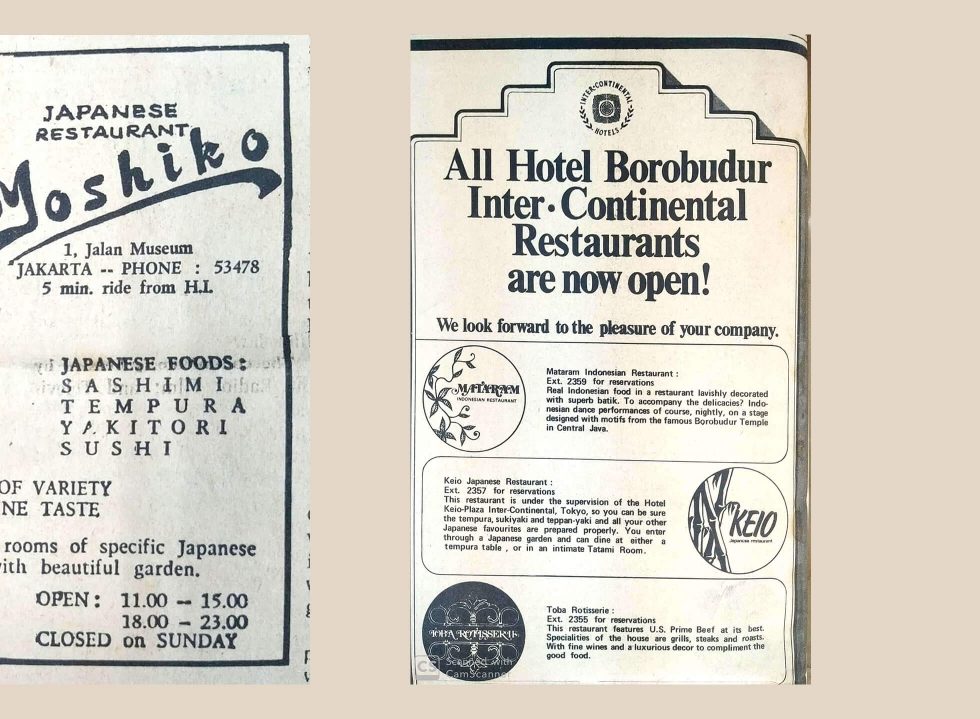

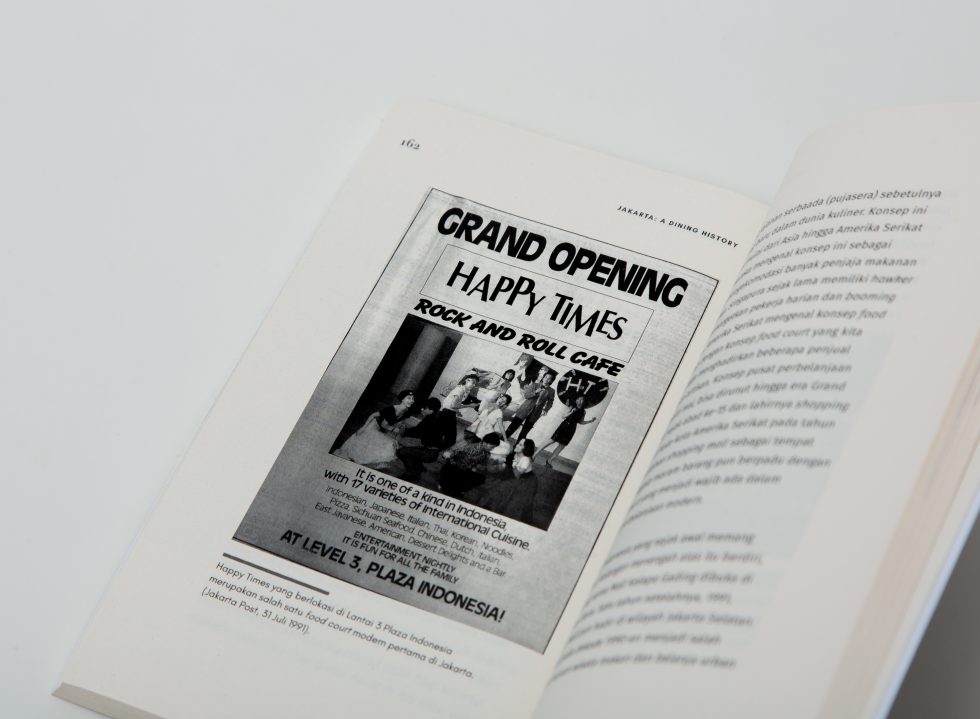

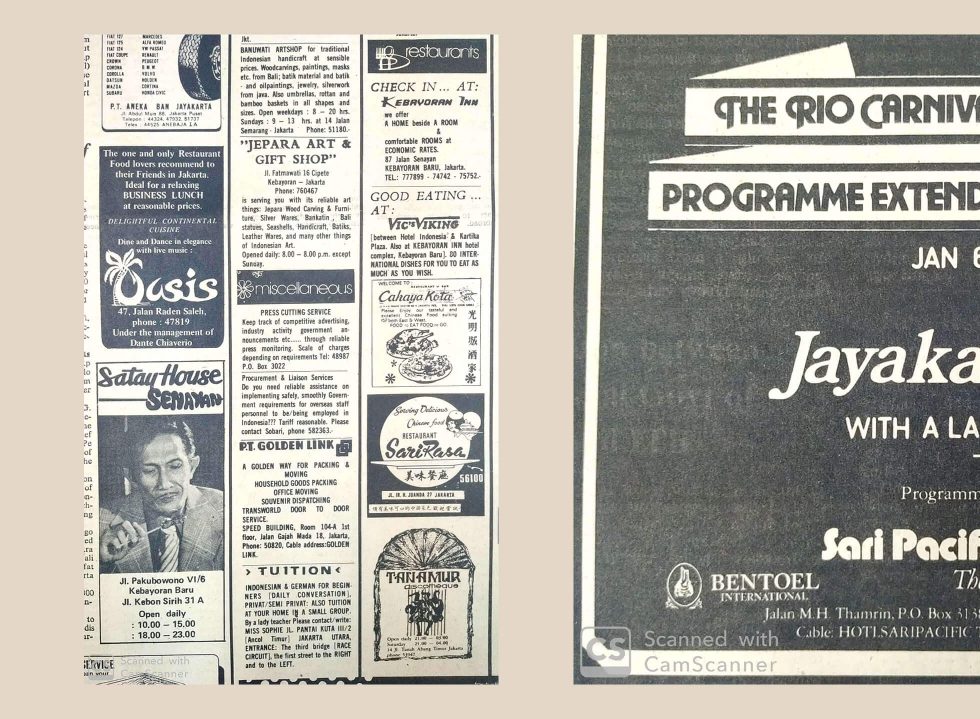

KS: That the movement of people and ideas was central to the development of Jakarta’s dining scene. The concept of grand hotels and dining was formed during the Gilded Age, that’s when New York’s The Plaza Hotel was built, and London’s iconic Savoy. I do not condone colonisation, but as historians, we have to admit that colonialism was part of Indonesia’s history, and it did affect how the restaurant and dining scene evolved in Batavia where European conglomerates resided. From the late 19th century to the early years in the 1900s, restaurants served Dutch and French cuisine and were only accessible to Europeans and educated locals. Then as time progresses, the types of restaurants that emerge vary too, upscale and midscale. Local restaurants emerged offering Chinese cuisines, and with urbanisation, regional cuisines flocked into the city.

MJ: I feel compelled to ask what is the oldest still-standing restaurant today in Jakarta…

KS: The restaurant with the oldest building would be Tugu Kunstring Paleis, built in 1914. The oldest still-standing restaurant about to hit the 100-year mark is Wong Fu Kie serving authentic Hakka cuisine in Glodok, built in 1925. Then we have Maison Weiner, a small bakery founded in 1936. The rest, which includes all the Dutch cafés, clubs and restaurants are gone. It’s quite upsetting when you think that even their physical building didn’t survive.

MJ: For the younger generation, it may feel difficult to appreciate the long and colourful history of dining in Jakarta because we can’t visualise the passed-down legacy.

KS: And I’m looking at this with agony, so much pain. Jakarta was the international hub of lifestyle where the best hotels congregated, the most fabulous restaurants and clubs had high-profile patrons from all over the world. At some point in history, Jakarta was the best, a world-class city that evolved to become a melting pot of international and local cuisines with the potential to become the dining capital in Asia. It’s an unfortunate missed opportunity because you see countries like Singapore creating narratives to attract the world, meanwhile, we already have the stories engraved somewhere. The grass is actually greener at home, and if the Jakarta: A Dining History book could serve anything, I want it to open people’s eyes to this reality.

MJ: What do you think can be done to leverage the dining scene in Jakarta once again?

KS: Thanks to our younger generation who are generally more globalised, informed and educated, they are holding up the culinary scene in Jakarta with the most spirit it has ever seen. From promoting local products to creating interesting dining and food concepts, we’re currently living in a dynamic scene that has amazing prospects to advance the industry, to see how this will look in 10 years with the current generation at the forefront of it. And from the perspective of a writer and observer, it’s incredibly exciting.

MJ: Do you think a situation like the pandemic can bring about the changes you wish to see in the local dining scene?

KS: Absolutely. First, it’s through the creative collaborations restaurants execute to survive the pandemic together. Secondly, the pandemic has made good food more accessible with upscale restaurants accepting deliveries, which was previously unheard of. Not only that, the pandemic pulled many people into cooking. By definition, that means more and more people understanding and learning the complexity of cooking, which in turn elevates their own standard for good food. I would even say that there’s a surge of talented home cooks. And if we observe the trends elsewhere, like in the United States, England and Australia, the presence of brilliant home cooks directly impacts the quality of food being served in restaurants. This brings me to my third point: restaurants are now challenged by the rising standards of their markets, which is urging establishments, their cooks and chefs to be even better and more creative when it comes to culinary progress. In any way, for me, this is indicative of exciting progress for our city.