Inside the long-standing building of Mu Gung Hwa supermarket on Senayan street, a couple of Korean families and some local shoppers were seen sifting through the well-stocked shelves of pantry goods for the week’s groceries.

There’s a sundry of Hangul-written ramen brands from Ottogi to Nongshim Shin Ramyun; in the cooler section, fresh cabbage to make kimchi (grown at a farm in Cipanas with seeds brought from the Korean peninsula) sit between radishes and other vegetables; in another aisle, a spread of plastic-wrapped tteok, from the rainbow rice cakes usually eaten during birthdays to honey-seasoned rice cakes of yaksik, take on many shapes and fillings.

In the past ten years, this integration between Korean and local communities has become a rather common sight, a result of the formidable Korean wave that has imprinted its mark in stages, from TV dramas and K-Pop, further into food, fashion and cinema. “Before, people who came here would be 80 per cent Koreans and 20 per cent locals. But I’d say now, it’s the opposite,” observed Nicolas Kim, the second generation who currently runs the Korean supermarket and distributor, Mu Gung Hwa.

While many locals consider Mu Gung Hwa as a portal to experience what they see from their favourite Korean dramas (wrapping BBQ meat in a leaf wrap, making a soju bomb, eating ramyeon straight from the nickel-silver pot), the mart is also a solace to Koreans adjusting to life outside their homeland, where Korean food products can reconnect them to the familiarity of their day-to-day routines back home.

“I come to Mu Gung Hwa once a week,” shared Sunny Park, who moved to Jakarta last year with her family from Seoul. She is originally from Masan, a district in the South Gyeongsang province. “Whenever I miss Korean food, I would buy one pack of Mu Gung Hwa’s kimchi and one pack of pork belly, and I’d feel like I have returned to my hometown.”

“The Kimchi Man”

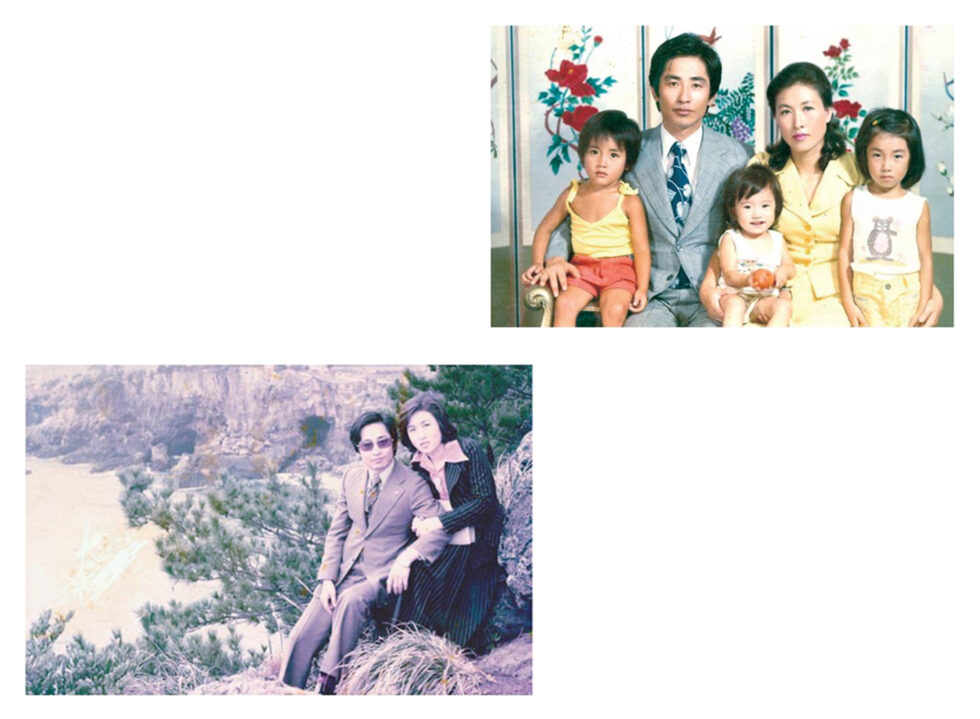

Founder Kim Woo Jae, who left South Korea in 1977, has often been credited by local news media for laying the cornerstone for the “Little Korea” neighbourhood in Senopati with the establishment of Mu Gung Hwa in 1980.

But his start was actually in Kalimantan, toiling away in a jungle on a log development project. After three years of fruitless labour, Mr Kim decided to move to the capital city where he was soon joined by his wife, Park Jemma, and three children. “Life was hard in Kalimantan. Compared to living in the city, even though we had no money, life was still easier here,” reminisced the 80-year-old.

According to Mrs Park (in Korean culture, it’s not customary for women to take their husband’s surname after marriage), a soft-spoken 78-year-old who goes back and forth between formal Bahasa and English, there were only about 200 Koreans living in the country back then.

Overcoming the language barrier was a challenge. The couple had to learn Indonesian from scratch by memorising the names of objects around them, such as cutleries. Mistakes, unsurprisingly, were common (they once got the Indonesian for spoon and fork mixed up), but it didn’t stop them from memorising up to 100 words a day.

“It started as a small, home business. We made kimchi at night while the children were sleeping,” Kim Woo Jae, founder of Mu Gung Hwa

The absence of Korean food at the time was also dearly felt; seeing this as an opportunity to change course, the husband and wife directed their attention to the food of their homeland. They started making tubs of kimchi, rice cakes and doenjang (fermented soybean paste) from the backyard of their Senopati home, and eventually, importing Korean food products into the country.

“It started as a small, home business. We made kimchi at night while the children were sleeping,” recounted Mr Kim who hails from Chungcheongnam-do province. His pride nagged at the back of his mind, “We can’t go back home if we don’t succeed here.” In Mr Kim’s 2012 autobiography book, “Indonesiae pin Mugunghwa” or in English translation, “The Rose of Sharon in Indonesia”, he recalled, “My wife’s eyes were getting tired of mixing spicy kimchi. The situation of sleeping only a couple of hours a day and staying up all night kept on.”

Brining the cabbage overnight, seasoning them with gochugaru (Korean red pepper flakes), and then sealing them in plastic bags, the couple could produce up to three tonnes of kimchi a day with the help of their staff. For more than four decades, their kimchi recipe remains more or less the same, with Mrs Park still personally overseeing the quality control to this day.

In the beginning, these batches would be offered to a small circle of Koreans living in the city; some were supplied in limited quantities to Gelael Supermarket, one of the oldest supermarkets in Jakarta. As orders increased, these popular banchan (side dish) were also flown to Balikpapan for other Korean workers there.

“At one point, we were loading bags of kimchi and delivering them by plane every day,” said Mr Kim. In the same book, he described the process “similar to the military’s way of transporting goods. The nickname I received at this time was ‘Kimchi Man’.”

A different kind of challenge

Even as their kimchi business thrived, the husband and wife knew they couldn’t stop there in order to sustain their family. This led to a bigger goal of opening a store that sells imported Korean food products, which laid the foundation for the Mu Gung Hwa supermarket chain.

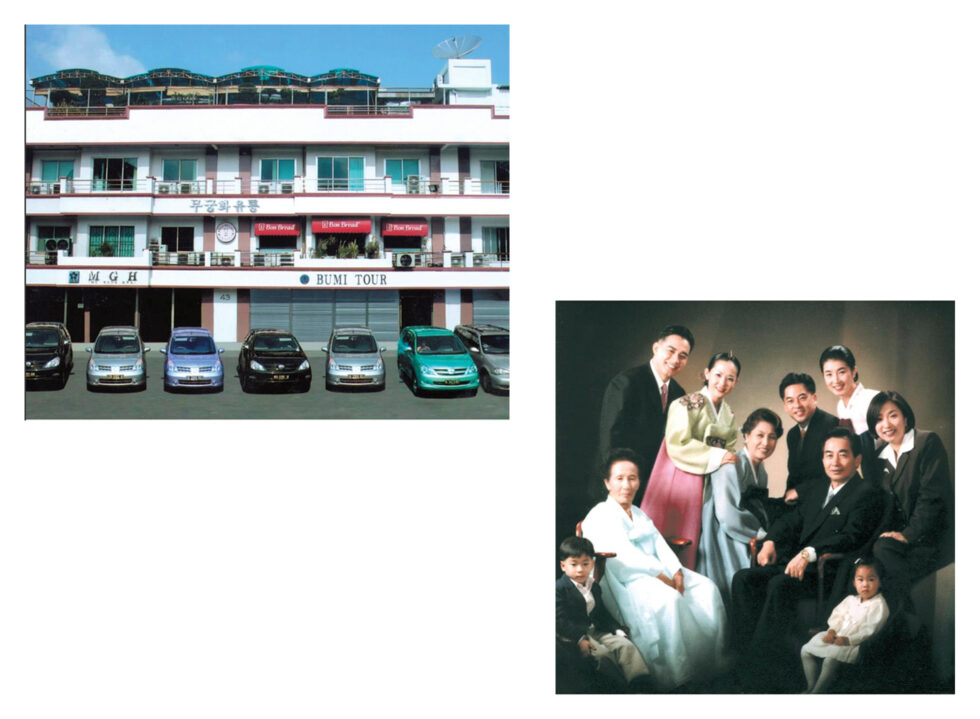

Today, there are over 30 Mu Gung Hwa outlets across the country, spreading its presence in major cities like Bandung, Yogyakarta, Medan, Palembang, and even remote towns like Bintan and Jepara. They are now one of the largest Korean supermarkets and food distributors in the city; the family business also added Bon Bread in 2007, the first K-bakery in the country.

This didn’t come without its own set of challenges. Nicolas, the current CEO and second born of the family, joined his father during the turbulent times of the Asian financial crisis and the infamous riots of ‘98. He still remembered the chaos at that time.

“It was mayhem, rioters were setting up fire here and there. We remembered how some trucks and bajaj would park in front of our store to keep us safe. I think it’s their way of protecting us since our business has been around for some time and my parents have been helping people around the neighbourhood.”

“I think Koreans and Indonesians share a similar palate,” Yang Soo Ryeo, wife of Nicolas Kim

Another hard hit came in 2017, when, coinciding with the rising popularity of Korean ramyeon, the Indonesian Food and Drug Authority (BPOM) did a huge sweep of the market to check for any fragments of pig DNA. A country-wide ban on Korean noodle imports soon ensued. “We had to pull multiple shipping container boxes out of the market and burn them all.”

Today, Nicolas is tackling a different kind of challenge with the changing times. “SNS (social networking services) has exposed many people to dramas, music, mukbang, and it’s these young people that digest new information quickly and want to explore new things,” said the 52-year-old. Hence when it comes to business longevity, Nicolas wants to embrace new ideas, which is fitting at a time when Korean culture has become ubiquitous in the country.

His son, Kim Min Gu, is a YouTube and TikTok content creator who makes cooking videos—ranging from pasta to Korean food trends—and vlogs on living as a Korean in a foreign city. He, too, felt the sweeping influence of his culture when he sees Indonesians as one of his platforms’ highest viewers.

“The world is changing so fast. My hope is that when the time comes, my children can bring in new perspectives and plans for the development of Mu Gung Hwa beyond just food,” shared Nicolas.

Coming together

Going forward, Mu Gung Hwa wants to focus on bringing together both Korean and Indonesian cultures into their mart. “I think Koreans and Indonesians share a similar palate,” observed Nicolas’ wife, Yang Soo Ryeo, who works alongside him for the mart’s daily affairs and the development of Bon Bread.

“I see a great interest in Indonesian food amongst Koreans, so we’ve started to include local products like tempe, tingting jahe, and local, quality coffee beans. [Through Mu Gung Hwa] we are spreading Korean culture, but at the same time, we are also introducing Indonesian culture to the Korean communities.”

Forty years on, the role and impact of Mu Gung Hwa have gone beyond the Korean community. Thanks to the family’s desire and ability to assimilate, Mu Gung Hwa is also about their camaraderie with fellow Indonesians. It’s seen from their day-to-day interactions with local staff at the supermarket to involving themselves in local traditions, such as sending out sembako (basic food needs) during the holy month of Ramadan.

Like the rose of sharon, the national flower of South Korea it was named after, Mu Gung Hwa’s journey reflects the same characteristics of hardiness and ability to survive under harsh conditions. It may have taken a while for Mu Gung Hwa to fully bloom, but what was once a lone Korean market within the area has become a foundation that inspired others alike to sprout in the city. But at its core, Mu Gung Hwa is a simple story of hard work and dedication, where both Korean and Indonesian roots are celebrated.