Suddenly, freeform shapes, wacky playful designs and vibrant clashing colours seemed to pop up everywhere. From incense holders, vases, glassware to furniture, objects that embrace such quirks are the kind of joy many crave in their homes these days.

Some called it the comeback of the ‘80s Memphis Design movement. Others pointed out influences from the rise of artisanship and personal expression, trends that were already forecasted pre-pandemic but became more pronounced in the past two years.

“Perfection, one of the pillars of minimalism, can feel ‘fake’ and out of touch with the current realities of the world,” said Bianda Nevansky, a senior researcher at Nation Insights. In a specific study on this shift, she observed how the minimalist aesthetic people have come to know experienced its heyday after the 2008 financial crisis, in which many grew tired of extravagance and opulence.

In a similar vein, today’s visual directions and expressions take form in response to the current social climate that is further accelerated by the pandemic. The research company coined it ‘offbeat fun’, a form of expression that is born out of the feeling of confinement and powerlessness.

This, she said, manifested into “home objects and furniture (among many other things) that are full-fledged fun, ugly-beautiful and quirky. It’s an antithesis to the gloom and doom of the pandemic, where colours, vibrancy, nonsensical impressions trump the everyday mundanity.”

“I know that my work is not for everyone. In the beginning, some even asked me ‘Why are you limiting your customers?’” – Margaret Yap of Made by Margaret Yap

Sharing this sentiment is Margaret Yap, founder of the Pluit-based pottery studio, Made by Margaret Yap. “I feel like people ‘snapped’ during the pandemic. With everything toned down, there’s this side of explosiveness in them as if they want to shout out,” the 31-year-old observed. “So, products that have been emerging appear to be more playful and ‘loud’. Being at home also makes people explore themselves further; they want to try something different and step away from what’s monotonous.”

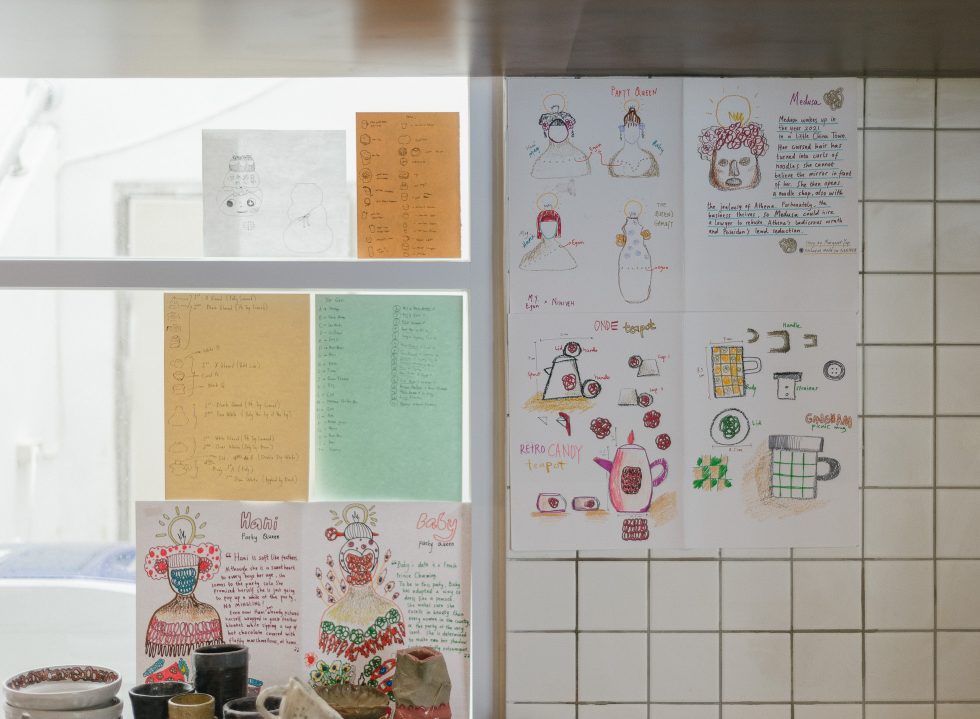

This looming trend also shifted the attention to her unique pottery creations. Established in 2017, Margaret’s collection of ceramic lamps, mugs, bowls and vases are, as she described them, “quirky, whimsical and loud”. Each clayware, moulded with techniques she honed in for years under the mentorship of veteran ceramist Adhy Putraka, gains its character through her hand-painted illustrations and doodles that are almost childlike, such as the wavy ‘bakmie’ pattern signature to her brand.

Each piece is ‘alive’, with Margaret ascribing character names and stories as if they exist in some make-believe land. Characteristic of the brand is also the ‘messy’, dented forms that shape her pottery, a contrast to her husband Steven’s polished and strive-for-perfection creations, along with her exploration of clashing colours. Yet all these unusual elements make sense in her head, and more and more, she observed, are gravitating towards her style.

“I know that my work is not for everyone. In the beginning, some even asked me ‘Why are you limiting your customers?’, so I contended that my products are niche. But over the years, I realised that many find compatibility with my designs. A lot of my students reside in the south [of Jakarta] and they would travel all the way to Pluit to get their training here,” told Margaret. “I’m creating my own world with how I create and present my pieces and people want to go inside it. It’s like I used to be indie, now I’m pop.”

“Perfection, one of the pillars of minimalism, can feel ‘fake’ and out of touch with the current realities of the world,” – Bianda Nevansky, a senior researcher at Nation Insights

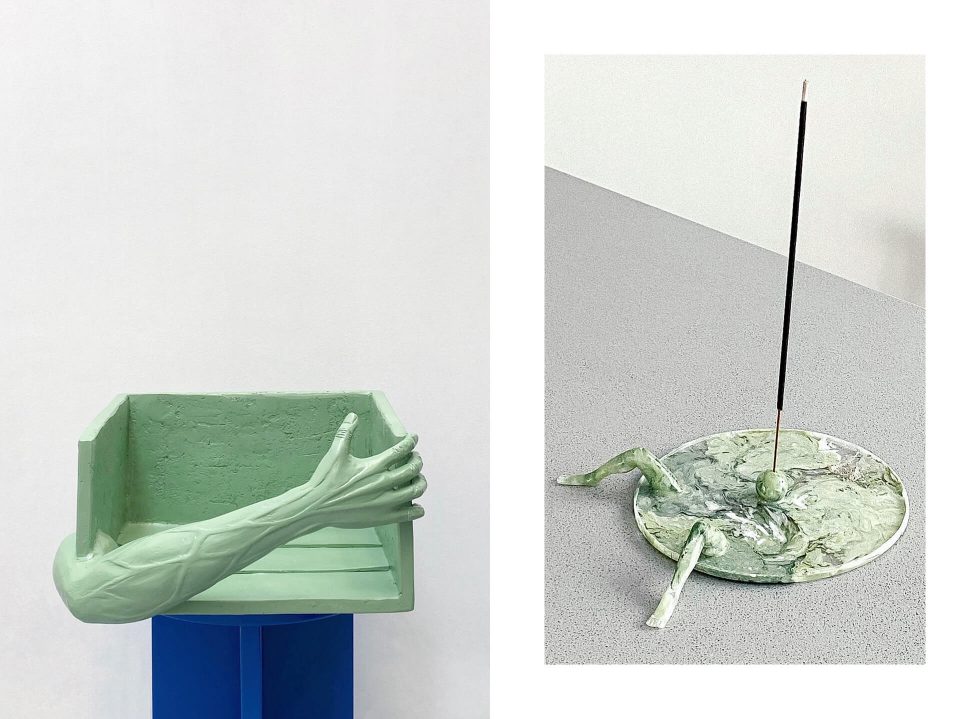

This continued focus on eclectic designs with a free approach to personal style also resonates with Abu and Bulat. Kicked off in the early months of the pandemic, the furniture brand first ran with the idea of making storage for vinyl records and accessories as Cen, the co-founder, was struggling to find them on the market. So she designed a medium-sized open box with a hand enveloping its front side, which turned out to be a flexible storage space and a sculptural piece on its own.

The initial idea quickly expanded into homeware, including incense holders, vases, mirrors, even rugs and pillows. Exploring curves, imperfect textures and daring colours, most products are hand-built at their workshop in Bogor, utilising mainly resin for the material. They currently only make five to seven pieces for each design and already see a lot of the products, particularly the hand-shaped objects, selling out fast.

“The visual process of Abu and Bulat comes from these everyday sights that tend to be overlooked [like the hand],” explained Cen, who is also the brand’s designer. “I thought, why are we just capturing these in our minds and not bringing them to life? Maybe the result will be absurd and random, but it can be a statement piece enjoyed by many.”

Cen also felt that these directions are accelerated by the current situation. It, in turn, widened the potential for designers and makers to get really creative. “Many were forced to have this free time, and it triggered a lot of people to ask what they can do in this situation,” she continued. “We’ve encountered local brands that create ashtrays from clays to those doing customised rugs, and we love seeing these pop up in the market. It turns out there’s an audience in Jakarta that shows a lot of interest and enthusiasm for objects that offer such styles and silhouettes.”

“Maybe the result will be absurd and random, but it can be a statement piece enjoyed by many.” – Cen of Abu and Bulat

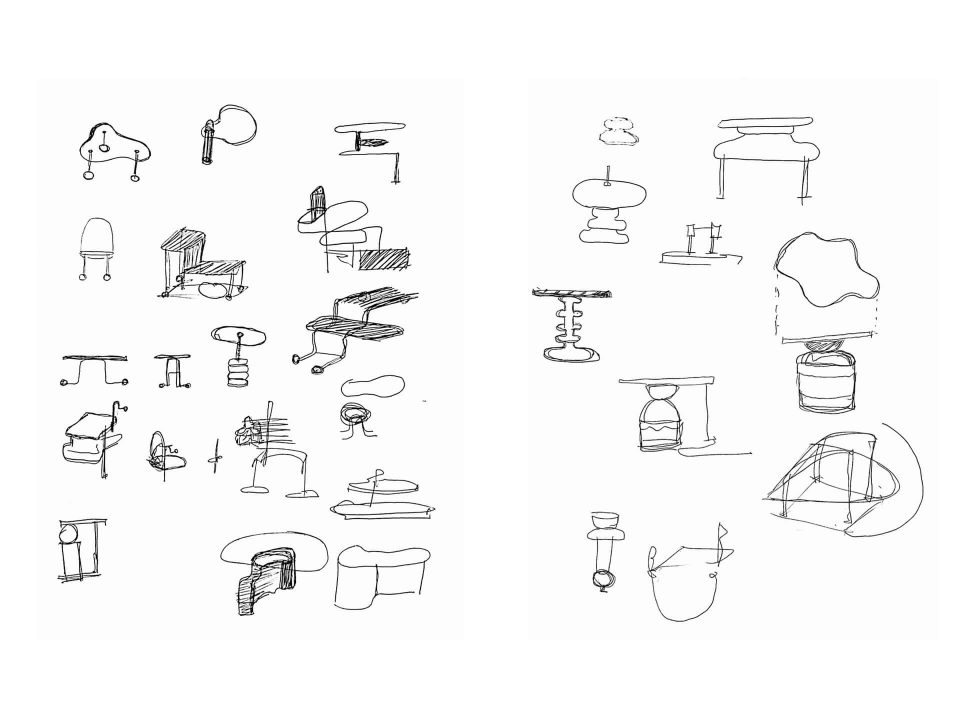

Also part of this evolution is newcomer Knob Knob, a local furniture brand founded by Candy Anthrasal and Angeline Kesia in 2020. Their story began in college, where both took up the same furniture class at Universitas Pelita Harapan and felt restricted by what was taught in theory.

“We were taught what is proportional and ergonomic, but we couldn’t identify with the feeling of the subject [the furniture]. Knob Knob is a fun project for us to question, release concerns, and fuse our two minds that are similar, but also different,” said Candy.

From rough sketches, trial-and-errors to actual constructions, each piece built in their small workshop in Kemang plays up materials, forms and colours, as it tries to blur the lines between what is aesthetic and functional.

The result is a lineup of objects with forms that don’t seem to play by the rules; there’s the stackable “Chin Chair” that fuses both soft curves and round shapes, and the multiuse “Kpole” standing pole with its bent lines, to their first-made product “Stooble” (stool and table), which explored the materiality of steel and acrylic.

“We want to give space for our customers, stimulate their curiosity and let them define the products themselves.” – Angeline Kesia of Knob Knob

“It’s hard for us to describe Knob Knob’s personal style. We both hold these ideas of what each piece may look like as well as its function, but it’s always going to be loosely defined,” explained Angeline. “We try as much not to segment our products. We want to give space for our customers, stimulate their curiosity and let them define the products themselves.”

The duo also started Casa Goods, their curatorial project of furniture, lighting and interior objects. In a similar vein to Knob Knob, the shop boasts items that offer unconventional styles and designs, from bulbous sofas, wiggly-shaped utensils, to colour-blocking glassware. “Our curation process is a long coming together. We source them from the U.S., Asia and even locally. We started selling them online and many people find it interesting, maybe because the pandemic has made many people think about the comfort of their own space,” said Candy.

Following people’s growing interests and enthusiasm toward Knob Knob and Casa Goods, both see that the market is indeed reacting to the evolution in visual style. But instead of fitting it in the frame of the pandemic, Candy and Angeline regard it as a constant change that moves with the times.

Angeline concluded: “Humans get bored. I feel like the shift happens because the era of minimalism has become so commercialised to a point that it’s everywhere. But every era has its own moment, and there will be repetitions; we may shift towards the quirky and unique styles now and go back to minimalism in a few years with a different approach.”