From the scores of cities in Indonesia, the metropolitan city of Jakarta certainly oozes with potentiality and urban allure. Despite this, the city is blanketed with noise. It’s not merely just literal racket from its densely populated inhabitants and the uncontrollable traffic. The Art industry has unfortunately been swallowed up, figuratively, by noise too. It’s the din of dizzyingly optimistic tune on the profitable growing art market.

For many artists in Indonesia, Jakarta serves as a doorway to Indonesia’s contemporary art scene. Yet that very fact also means serious competition as artists pool in this capital city, attempting to make their mark nationally, and fingers crossed, internationally as well. And so, artists tend to ‘shout’ rather than ‘articulate’ through their art. This too, has caused the audience to only ‘see’, rather than ‘hear’ what the artists are trying to convey.

Natasha Gabriella Tontey may not be a household name for many, but she is certainly making sure her presence is being felt amidst the cacophonies. Yes, for many who are familiar with her, her works do possess loud quality. But, it is a shout with calculated purpose instead of shocking novelty.

It’s hard not to be drawn in by her art. Take Rhyme Stew for example. From a distance, it appears buoyant, jolly and enchanting. Yet, as you inched closer, something is off. While it is no less enchanting, the same can’t be said for buoyant and jolly. Dismembered doll parts swim in a puddle of solidified pinkish goo that most likely to appear as ghastly nightmare for girls under the age of ten. Still, amidst the visual, there lurks an uncomfortable message about how warped childhood has become in our era.

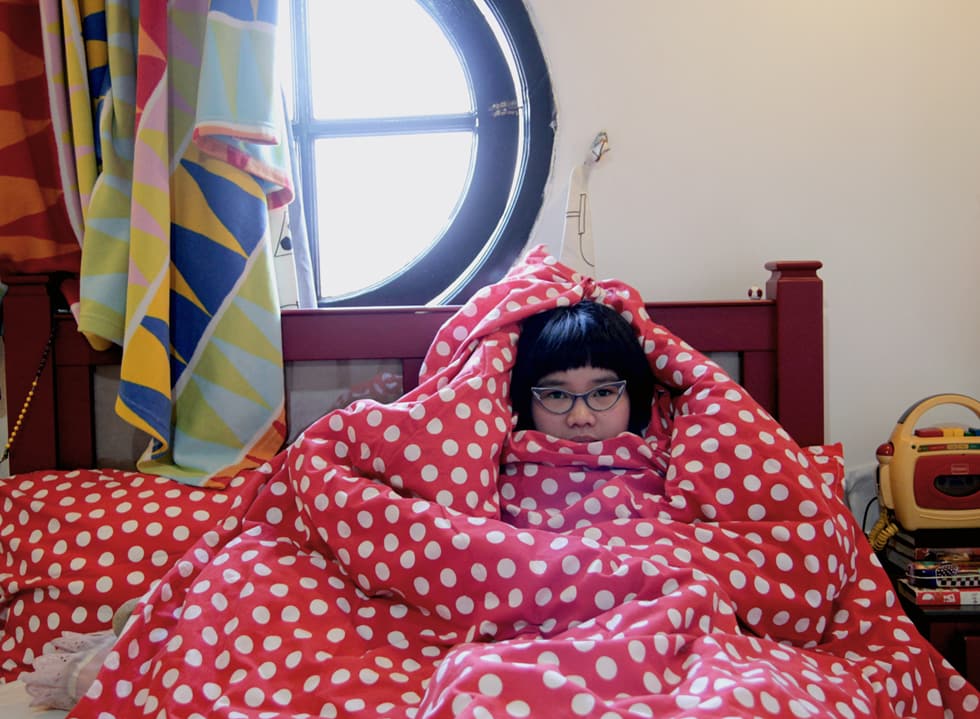

In a late afternoon, after a few confusing turns into a district in East Jakarta, the modern world slowly morphed into a sleepy neighbourhood. Here at this time, the street is ruled by one or two senior citizens enjoying a siesta on the bench while an alarming number of stray cats roamed around leisurely. Dressed in a red overall covered with white polka dots over a white t-shirt, Tontey’s presence immediately strikes a defying contrast against the dull surroundings.

“Come on in,” she welcomes me, glancing through her cat eye glasses.

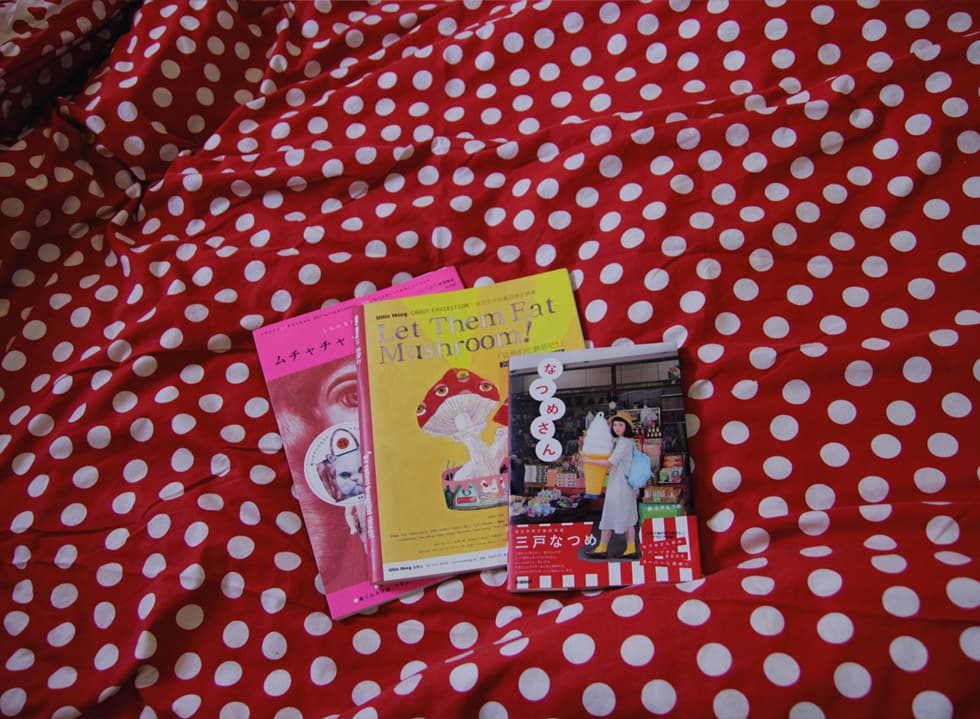

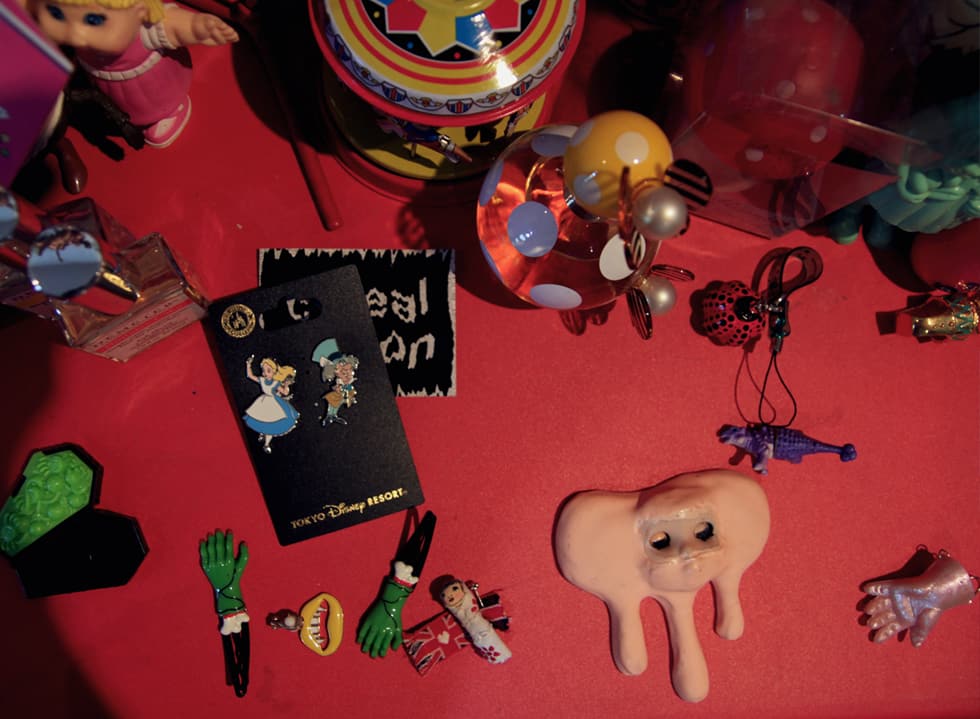

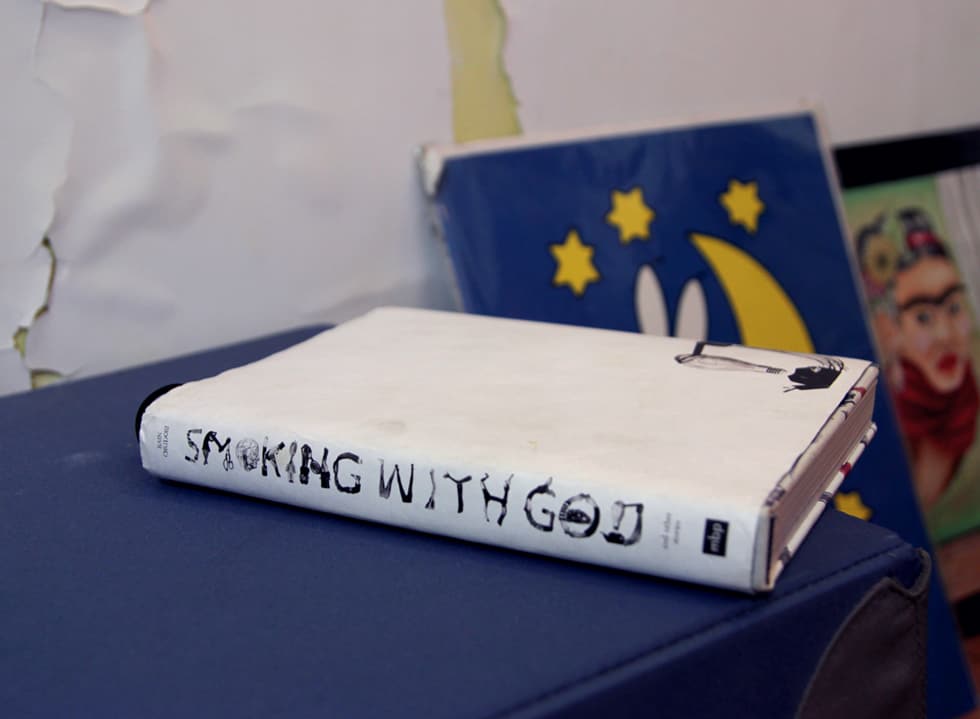

As we proceed to head into her room upstairs, it’s hard not to feel as if you’ve tumbled down a rabbit path straight into a wonderland. Not the Alice’s version, but Tontey’s. Among the toys and memorabilia of cats and mushrooms in her room, dismembered Barbie doll parts festoon the surrounding like prized possessions. Their cheery smiles only serve to add an air of sinister to the space. Despite those, Tontey looks perfectly at home.

“I just summed up my entire childhood, didn’t I?”

While the quirky appearance of Tontey immediately casts her as an eccentric figure, destined to be a part of the beguiling world of Art, it wasn’t until college that she started to actively educate herself on the subject of Art.

“At that time, I didn’t have much knowledge about local art schools. So I ended up in Graphic Design instead,” she says. It must have been a retrograde step for her as she dreams of being a painter since young. But, as always, fate has its own way of leading one into an unexpected turn.

“I joined Galeri Foto Jurnalistik Antara (an institution specialising in photojournalism) for photography workshop while studying Graphic Design in Pelita Harapan University. From there, I was introduced to the works of photographers, such as Man Ray and Oscar Motuloh. Motuloh has a background in photojournalism but his work can also be interpreted as Art. So I’m really curious on how he achieves that,” she recalls.

“I started to question the subject of Art itself, its boundaries because I realised that there are more to Art than just paintings, than just what everyone thought it should look like,” she continues, in a tone so soft that I often find myself leaning over to catch her words. But whenever I lean forward, she would tilt her head down sideway. When she does that, her one-eyed earring on one side of the ear, framed by her short mushroom bob, glares at me intensely.

After dabbling in photography and enlightening herself on the subject of Art, Tontey took a significant step in her career as an artist, being one of the artists to exhibit in exi(s)t – an exhibition that aims to promote talented artists without any background in Art. And it is in this exhibition that she showed Rhyme Stew, where her work is “thick” with the topic of childhood.

The topic of childhood continues to recur in her subsequent art works. She opens her laptop and shows me some of her past works. In Abandoned Childhood, viewers gazed into a viewfinder to images of weirdly re-arranged body parts of dolls. The constant smiles worn their faces hide the painful truth about the state that they’re in.

“I want to highlight the kind of childhood where children grew up under the care of their nanny instead of parents, where the love of their parents comes in the forms of toys and money. Thus, with the viewmaster, I want the viewers to see it from my point of view,” she explains in a hush tone and pauses suddenly.

“I just summed up my entire childhood, didn’t I?” she guffaws with an unsettling voice that seems to be drawn straight from her diaphragm.

“It often started off as something personal but then it slowly develops to more than just that.”

Born in August 24th 1989, to a small family of four, her parents’ busy working schedule in the oil industry means they are often away from home, from her. While she has an older brother, their huge age gap resulted in Tontey being left to her own device for most of her childhood.

“My parents are rarely in Jakarta. They only come back once every fortnight or sometimes even longer than that. Even though my brother and I live in the same house, we’re more like two housemates living under a roof. We rarely talk to each other. So I’m often alone,” she shrugs.

No doubt this grim childhood experience left a big impact on her. Still, as the saying goes, every cloud has a silver lining. The absence of her parents and brother has resulted in her actively engaging in her own imagination in order to keep herself entertained. Not to mention, the experience has also made her much more independent.

“Thinking back, I guess it’s a good thing because it made me much more independent. Still, back then it’s completely the opposite, especially when you’re registering for secondary school without the company of your parents. But it’s different now. Even though I still rarely see them, they are always present for my every exhibition. But, taking pictures most of the time instead,” she lets out the unsettling guffaw again, as if claiming victory.

Still, to focus on the subject of childhood and drawing it from her own experience, it must have been very personal then?

“It often started off as something personal but then it slowly develops to more than just that. Such as, the research that I did for Abandoned Childhood leads me to the idea of the introduction of wealth during childhood,” she explains.

And the latter is the core of Serba Serbi Uang – her interactive visual artwork for Jakarta Biennale this November, together with other seven young visual artists in Galeri Salihara. Through the use of different mediums – video animations, books and murals, she invites the viewers to participate and to trace back their first ever concept of wealth through playing.

“Perhaps, it is about revenge.”

Nevertheless, even after actively exhibiting her works for more than a year, not to mention Jakarta Biennale, Tontey remains grounded. In fact, she is thinking of joining artist-in-residence – a program that allows artists to stay and work in other countries in a conducive environment and facility that benefit them creatively.

“I want to get out of my own comfort zones. Who knows I might be exposed to other subjects that I’m interested in as well. For example, right now the subject of my work in Jakarta Biennale touch on the idea of the introduction of wealth during childhood but I can continue to develop it further to address other issues that are tied to similar themes,” she explains.

I ask her on what is the most important trait an artist should have. She pauses for a while and replies, “Anxiety.” I raise my eyebrows, about to ask why. Anticipating this, she continues, “It is so that I can keep questioning, to make sense of the things that are happening around me.”

And by trying to make sense of the things happening around her, it is inevitable then that it often leads to a time where it affected her most – her very own childhood. “Perhaps, it is about revenge. Maybe subconsciously with my parents, with the surroundings or simply with myself,” she reflects, again in a soft tone.

But then her voice picks up. This time round, with her eyes and her one-eyed earrings fixing their sight confidently at me, she concludes, “Still, at the end of the day, I want to do it in a way that pleases me. Through Art.”