In Indonesia, islands stretch to vast thousands. Within it, lay a small chain of islands; one even more bountiful than the other. There, volcanoes sit tall against the horizon, its soil yields only the ripest fruits. But this is all popular knowledge. Unbeknownst to most, a whopping number of Europeans sailed the sea only to die before reaching its harbour and the natives bled, both for a spice whose value once eclipsed the worth of gold.

This is the story of Banda, a clutch of twelve islets that made Indonesia possible, and whose endless repository of nutmeg set in motion the birth of many firsts: the first system of European colonisation, the first implementation of global monopoly enabled by spice routes, and to its islanders’ misfortune, the first mass genocide to ever happen in the East Indies.

At one point in history, the islands of Banda in Indonesia changed the world at the cost of its people.

“Christopher Colombus even accidentally discovered America on his way to the remote spice islands in the Far East,” said Muhammad Fadli. The Sumatra-born documentary photographer is the man behind the photos gracing “The Banda Journal,” a book published under Jordan, jordan Édition, which he worked in collaboration with writer Fatris MF.

The aspect of humanity is fundamental to Fadli’s works, focusing his lens on socio-political crises alongside urban subculture for publications like National Geographic, The Wall Street Journal, Der Spiegel, Forbes Asia and Das Magazin. In 2020, he photographed for The Washington Post’s article on the exhumation of a cemetery in West Java for a gargantuan resort project tightly affiliated with The Trump Organization. The pictures express the sorrows of the affected villagers: a farmer-turned-construction-worker, who had the remains of his four brothers dug up and removed without his family’s consent, posed in front of a half-built house, his eyes wet and bloodshot. Another shows a woman standing in a barren cemetery where her two daughters used to be buried, now nil.

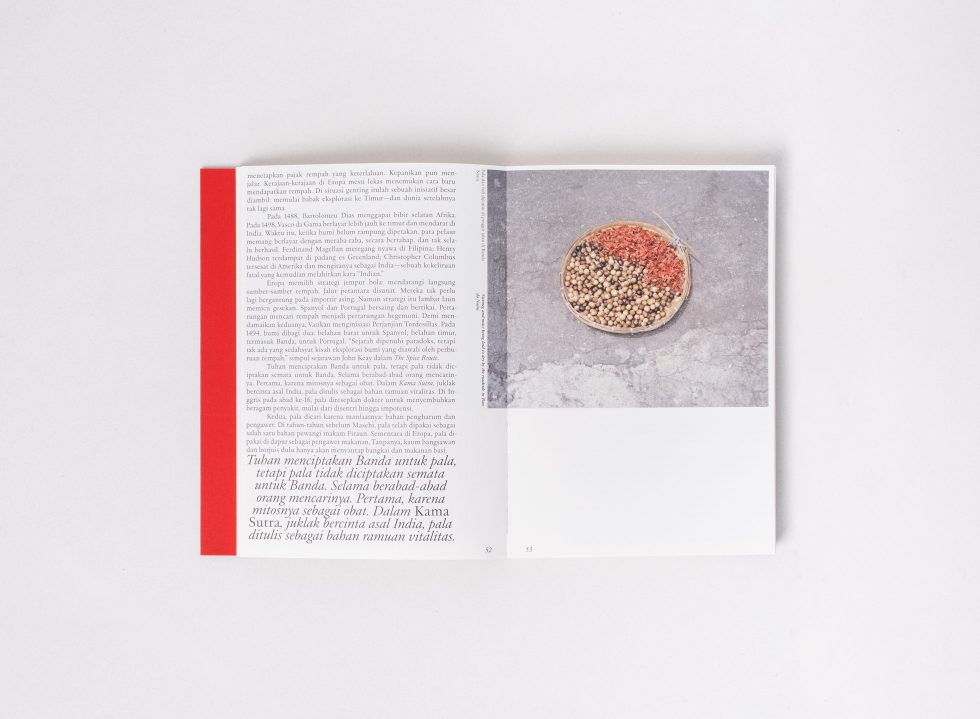

“God created Banda for nutmeg, and through nutmeg we understand Banda.”

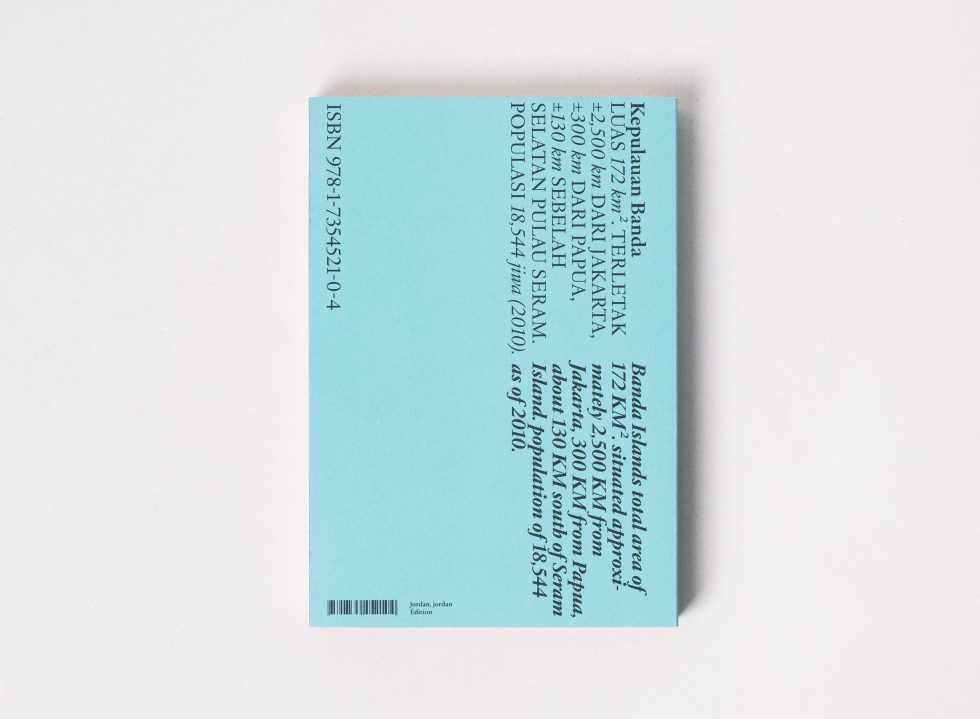

“The Banda Journal” unfolds a story of similar nature. Stretching 240 pages, the book narrates how the centuries-long exploitation in Banda Islands, a forgotten place that was the earth’s only producer of nutmeg and an obsession to powerful European nations, persists as a history brushed aside by a world that keeps pacing swiftly forward.

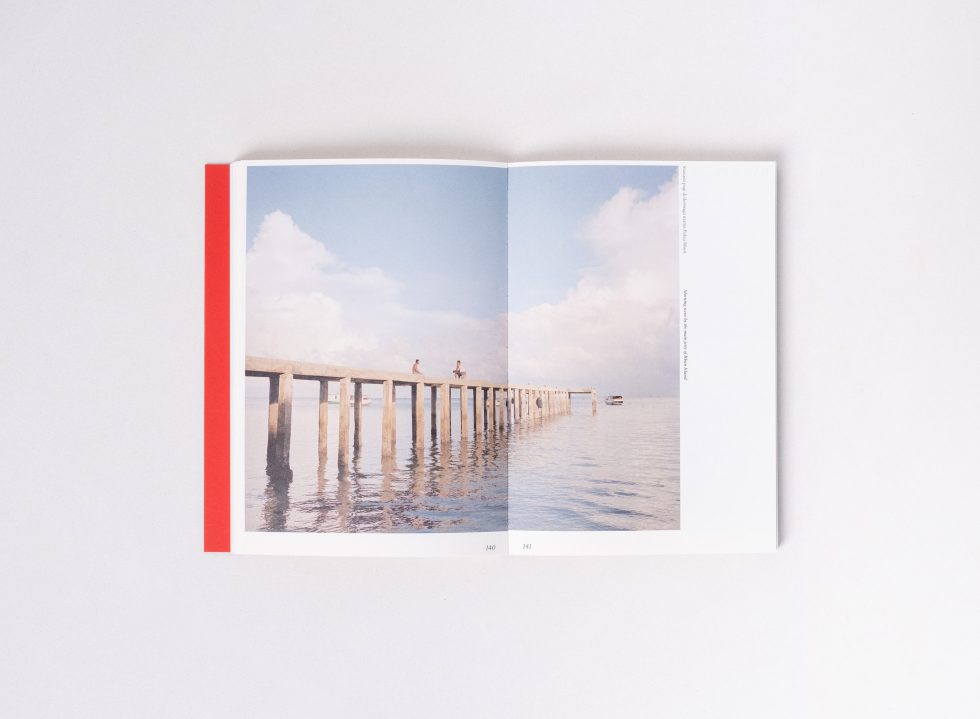

The book spans eight chapters, explored through a series of texts and photographs that encapsulate the daily lives of Bandanese, like the life within a classroom in a local village to the heart-wrenching past of its islanders ravaged by bloodbaths that entailed the European’s discovery of Bandan nutmeg and colonisation. It also arches over the island’s beauty of nature and vast blue oceans, to socio-cultural remnants like ruins built with the distinct architecture of the East Indies, to a bitter lullaby in a nearly extinct language that still sings of Jan Pieterszoon Coen, the Governor-General of the Dutch East India Company responsible for the manslaughter of Bandanese people on 8 May 1621; a genocide that reduced Banda’s population of 15.000 lives to a trifling 600.

Fatris, a writer with a flair for philology, wrote in detailed observation of his experience in Banda: “I saw how the Bandanese lived side-by-side with old forts covered in moss, canons, and other vestiges from centuries past that seemed trapped in a strange dimension,” read a sentence in the forewords.

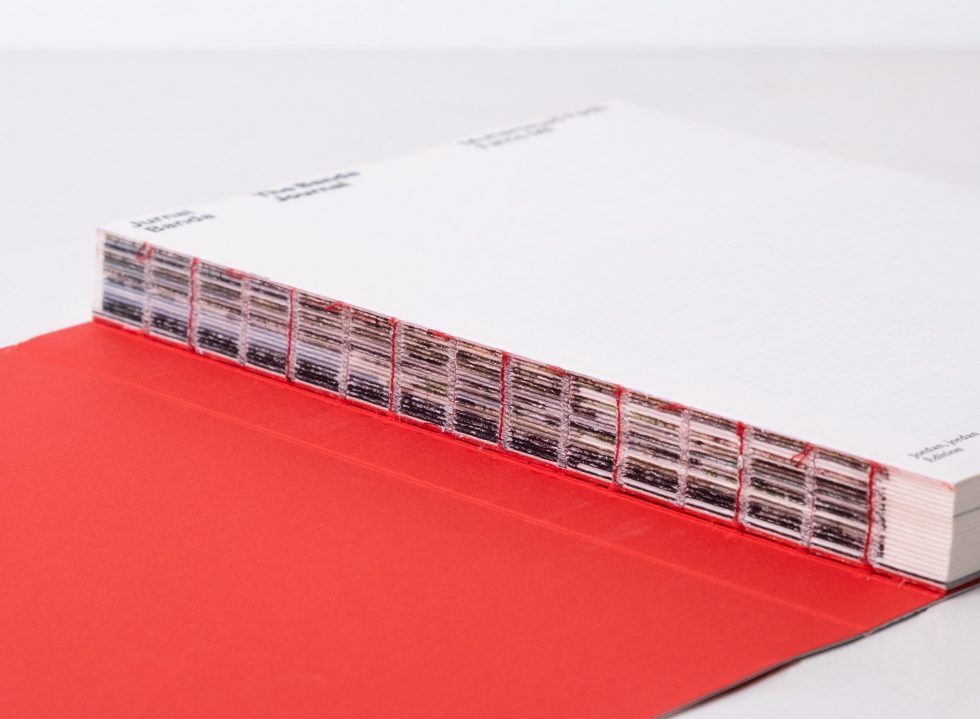

Behind this visual-heavy journal that comprised 108 images are 150 film rolls Fadli spent photographing the islands, and countless hours of Fatris mingling with the locals. At one point, the writer taught local students literature: under his brief tutelage, they wrote letters to and of Banda. Ten of its scanned copies occupy a few pages in the book.

The research for this documentary project traces back to 2014, with Fatris being the first among the two to traverse Banda Naira and its three neighbouring islands. The echo of a violent past that once dominated the outlying islands remains a memory too intimate to the descendants whose ancestors were assassinated or exiled, as told in the eighth chapter of the book, ‘Songs from Another Land.’

Six months later, Fadli sailed west from Naira to Ay island, where the battered ruins of Fort Revenge, a symbol of the Dutch conquest, remains. In the thick of a raging storm, his cruise on the Banda Sea took a tumultuous turn: the boat rocked violently to the pulse of an ocean that almost swallowed some tens of passengers whole. Fadli swore to never go back.

“When I realised even the locals started muttering in panic, that’s when I knew something bad was about to happen,” he shared during our interview in light of his recent publication, “but I went home and reviewed the photos I took. As I reflected on the stories that shaped them, I knew I had to return.” So their journey continued.

The duo sojourned in Banda, which Giles Milton, a British writer, reminisced as an island that “can be smelled before it can be seen” in his book “Nathaniel’s Nutmeg” (1999). As time went by, their findings of colonised Banda and the stagnant lives of its present dwellers became more heart-wrenching, more unheard of, and in a way, more unique.

The journal covers a broader scope beyond past tragedy. It also casts light on life in Banda today, where hopeful inhabitants live on unpaved roads and with persistent water and electricity crisis: a junior high student wrote about a desire to flee the secluded island to explore the world, a young girl wishes to become a teacher to evade the predetermined fate of becoming a nutmeg farmer like their parents before them.

In line with this air of optimism amid an unpromising fate is a snapshot of Kardi Husin, an ex-employee of PT Banda Permai—a municipally-owned corporation in the nutmeg business that was shut down due to corruptions—vacantly staring at the void.

At one point in history, the islands of Banda in Indonesia changed the world at the cost of its people.

People of the Banda diaspora, now mainly hailed from Java and Buton in Sulawesi, still rely their lives on the endemic plant whose monetary worth is a mere speck to what it was once. Pictures of the islanders against the backdrop of blue, albeit silent horizons were so strong and powerful in nuance that one could feel the stillness and despair true to life in today’s Banda. Some of the locals fish for a living, but the spice continues to hold a sacred role.

“God created Banda for nutmeg, and through nutmeg we understand Banda”, wrote Fatris.

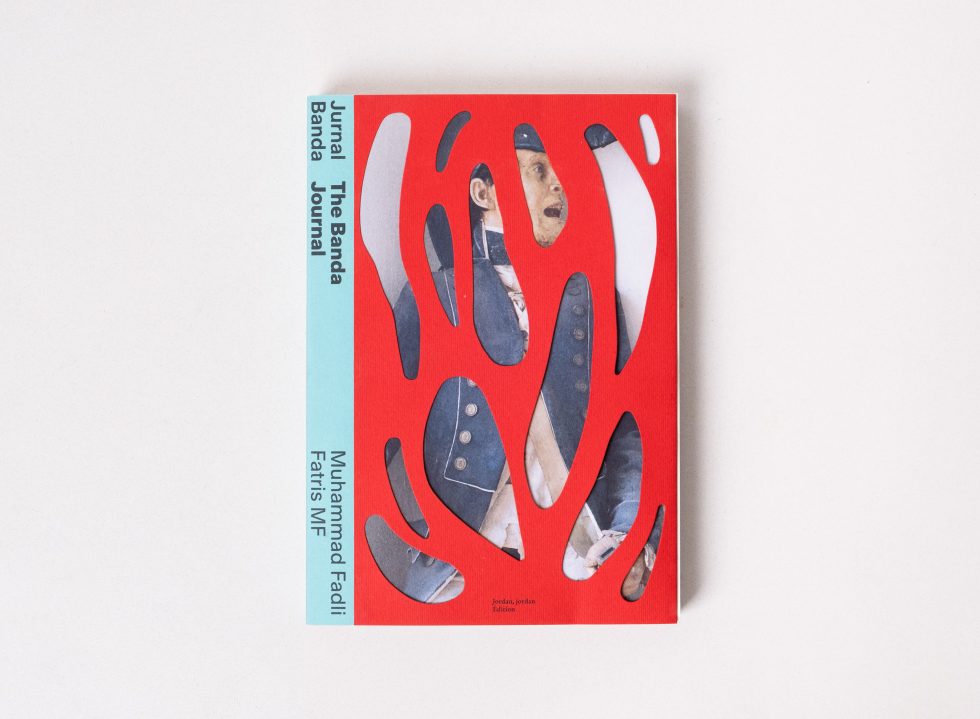

The built and design language of the journal—which one may find unmistakably Jordan—is also as ironic as the story of these forgotten lands. “When Fadli showed me his documentary project on Banda, I knew all at once that [The Banda Journal] cannot be published as a photobook, or coffee table book due to its complex, history-ridden topic. Through design, I helped him re-examine the visual direction that is more critical,” shared Jordan Marzuki, the designer and publisher of Jordan, jordan Édition.

The book’s front body is playfully swathed in a paper which forms a bright red nutmeg fuli or mace, while other parts of the cover scream the colour turquoise. This mesh of vibrant colours is paired with a decaying portrait of Captain Sir Christopher Cole (a British Royal Navy who commanded a successful coup against The Dutch in Banda) as its cover photo.

“It reminds me of what I learned in history lessons back in elementary school: The Netherlands was a cruel coloniser. At the time, I didn’t take it with much criticism how the long-term effects of colonialism relate to our lives today,” closed Jordan.

Inside, the writing makes the research-heavy materials speak with a vigour; percolated with personal anecdotes and, again, ironic compare-and-contrasts redolent of a black comedy.

“Photography and writing play a strong role in how we look at the world,” said Fadli, “But we have to realise that colonisers also employed that for their agenda. The question is, is it possible to use the same tools to achieve a different result?” he continued.

“The Banda Journal” may walk us through the history that made and stained our nation, but there remains an overarching message that prompts deeper collective grief: a post-colonial truth that demands greater action beyond domestic acknowledgement.

The literature, as if speaking loudly with regret, suggests that freedom does not always go hand-in-hand with empowerment. For nearly 80 years of Indonesian independence, the islands still persevere with the tension of a lost hope under a homeland that owes them everything but. What does independence mean in the face of a nation that shies away from giving back, or more so, the willingness to nurture? The journal confronts how it takes more than claiming sovereignty in order to truly rise from one’s knees.

Publisher: Jordan, jordan Édition

Category: Photo essays & Documentary

Date of Publication: 9 April 2021, Indonesia