It was a Saturday in the middle of March in Surakarta—or Solo as most people call the city. Humidity filled the air in anticipation of rain, amplifying the already dreary heat. In the heart of the city, unabated by the weather, Puro Mangkunegaran welcomed its usual roster of visitors looking to tour the palace.

Among them were a group of casually-dressed youth, foreign tourists with batik cloths wrapped around their waist—to abide by palace protocols of covering one’s legs—as well as families garbed in headscarves and modest attires. Guided by their respective abdi dalem (palace retainers), they gathered at the Pendapha Ageng, where, just the day before, festivities were held to celebrate the 266th anniversary of the Mangkunegaran Principality.

Off to one corner, a small gamelan orchestra played a time-honoured melody while a troupe of visitors took turns hugging the teak pillars of the pendapha, which is said to be the biggest Joglo-style pavilion in Asia. A myth surrounds these pillars: success comes to those who can wrap their arms around their thick beams.

Meanwhile, each guide had curious visitors probing into the history of the 266-year-old palace and the royal family that still occupies it to this day, the Mangkunegara dynasty. Gracing the walls of the puro are core members of the household from the 18th century to the present, who have their stoic expressions captured in paintings and photographs—all except the prince who started it all, Raden Mas Said aka Mangkunegara I (1726-1795).

“He was a fugitive. The VOC (Dutch East East Indies Company) wanted him dead for killing so many of their soldiers,” narrated an abdi dalem guide, Ibu Endang, from within the dimness of the museum-cum-ceremonial room called Ndalem Ageng. She then pointed above the sacred altar towards a wood-carved sun centrepiece; it was painted in signature Mangkunegara colours called pari anom, a pairing of green and gold-like yellow. “So instead of a portrait, you’ll find the sun symbol here called the surya sumirat (the shining sun) to represent him,” she continued.

Son of an exiled crown prince of the Mataram Sultanate in Central Java, Raden Mas Said led a rebellion in the middle of the 18th century against his own royal kins and their VOC allies. The prince was “the size of a small youth”, describes historian M.C. Ricklefs in his book “Soul Catcher: Java’s Fiery Prince Mangkunagara I, 1726-1795” (2018), citing the ancient book of poetry Babad Giyanti, which captured events from that time. And yet, his proficient skills in military arts quickly earned him the title of Pangeran Sambernyawa, or “Soul Catcher” in Ricklefs’ translation.

Consequently, the prince’s rebellion led to the famous Salatiga agreement, dividing Mataram into three territories, which included the Mangkunegaran Principality on top of the Surakarta and Yogyakarta sultanates.

“[The biggest strength] that I can see from [my ancestors] is their outlook.” Kanjeng Gusti Mangkunegara X, the current prince.

From multiple corners of the museum—surrounded by intriguing family artefacts such as the ceremonial gold crowns reserved for a sacred dance, chastity belts to prevent coital affairs (“They were locked with spells,” Ibu Endang chimed in) and a royal stamp in the form of a toe ring—the still visages of Mangkunegara I’s descendants now gaze upon visitors in the dusky room, each one with a story as arresting as the next one to represent a new era for the principality.

But none of the legacies in the room would have been there if not for the later actions of the first Mangkunegara prince, who seemed “to have abandoned any serious designs upon the throne of [Surakarta and Yogyakarta], and instead concentrated on an attempt to make his princely domain permanent,” wrote Ricklefs in his other book, “A History of Modern Indonesia since c.130” (1993).

Sacrifices were made and past grievances were put behind—but times have changed since he established his principality. Mangkunegara is now a cultural institution instead of a ruling power, and Pangeran Sambernyawa‘s descendants only maintain their titles honorarily.

Amidst the present social and cultural shifts that have seen old norms replaced with new thoughts and ideas at such a rapid pace, how does the Mangkunegara dynasty remain relevant and sustain itself?

Kanjeng Gusti Mangkunegara X’s grand scheme

“[The biggest strength] that I can see from [my ancestors] is their outlook. They were progressive for their time. Always adaptive and dynamic,” pondered the current prince, the 26-year-old Mangkunegara X, known to many by his honorific, Kanjeng Gusti. His portrait by famed photographer Darwis Triadi now takes up the pinnacle position on the terrace of Ndalem Ageng. And many of the visitors, mostly young girls, can be seen taking pictures alongside it.

“For example, during the reign of Mangkunegara IV [in 1853-1881], there was a lot of economic growth through industrialisation. He built sugar factories and cultivated gardens, while also writing works that promote collaboration and openness,” he continued.

Indeed, the flair for progress runs in the family. In 1933, Mangkunegara VII (1885-1944) became the founder of the Dutch East Indies’ first locally-owned radio station, Solosche Radio Vereeniging (SRV). And instead of broadcasting music from abroad, he favoured the traditional tunes of his homeland. It was his way of promoting local cultures in the face of globalisation and the continued promotion of Westernised ideals in the country.

Almost a century later, his great-grandson, the current prince, faces a similar challenge. “But it’s because of globalisation that we can reintroduce [the Mangkunegara] culture at a more significant scale. And we’re not just talking about Solo, but also Jakarta, the entire Javanese island and even globally,” opined Kanjeng Gusti optimistically.

It’s hard to imagine, but prior to his coronation less than a year ago, he was known to most simply as Bhre Sudjiwo, an associate working at a law firm in Jakarta.

The young prince was dressed in an elegant high-collared beige shirt as he walked down the path of Pracima Tuin, the newly revitalised royal park located on the west wing of Puro Mangkunegaran. It is among the first foundations of Kanjeng Gusti’s plan to usher the Mangkunegara dynasty into a new and modern era.

“I initially made the development plan for Romo (Father) during the pandemic, but [with his passing] I ended up using it myself,” revealed the young prince. It’s hard to imagine, but prior to his coronation less than a year ago, he was known to most simply as Bhre Sudjiwo, an associate working at a law firm in Jakarta.

At Pracima Tuin, a newly-built restaurant with the appearance of a European glass house shone brightly under the late afternoon sun. Called Pracimasana, the menu items on offer are passed-down recipes kept and preserved through the centuries by the abdi dalem kokken (retainers working in the palace’s kitchens), tweaked in a way that caters to a modern audience. A case in point, there’s the appetiser Brubus, a favourite of Mangkunegara VII, where a mix of ground meat, garlic and shallot is wrapped with cabbage and then plated alongside aromatic ginger sambal and thickened coconut milk.

The restaurant seems to have quickly found its market. Just a couple of months since its opening at the beginning of the year, it has received a flood of reservations; from ladies in batik dresses taking snaps with their confidantes, young couples on dates to neatly-dressed families gathering over lunch.

On the same ground, plans to open a lounge, a café and a workshop-slash-exhibition space are also underway–each one with a narrative that links back to the history and life in the principality, which visitors can experience first-hand through the park.

For example, the lounge will house a barbershop in the same location where past Mangkunegara princes used to have their hair cut. And within the same room, a cigar bar is also in the works, representing the tobacco business that used to fill Puro Mangkunegaran’s coffers.

“We want Pracima to be a place where the culture and legacy of Mangkunegara can be cultivated and shared with the public in a meaningful way,” explained Kanjeng Gusti of his plan. “We have to evolve, according to the situation and the era. So now if we’re a cultural institution, we act like a cultural institution.”

Reigniting past traditions

In The Hague, 86 years ago, a young member of the Mangkunegara dynasty performed a dance for the wedding of the then-princess Juliana of the Netherlands. The dancer was Gusti Nurul, the renowned daughter of Mangkunegara VII who captured the public’s fascination with her beauty, grace and command of traditional Javanese dances.

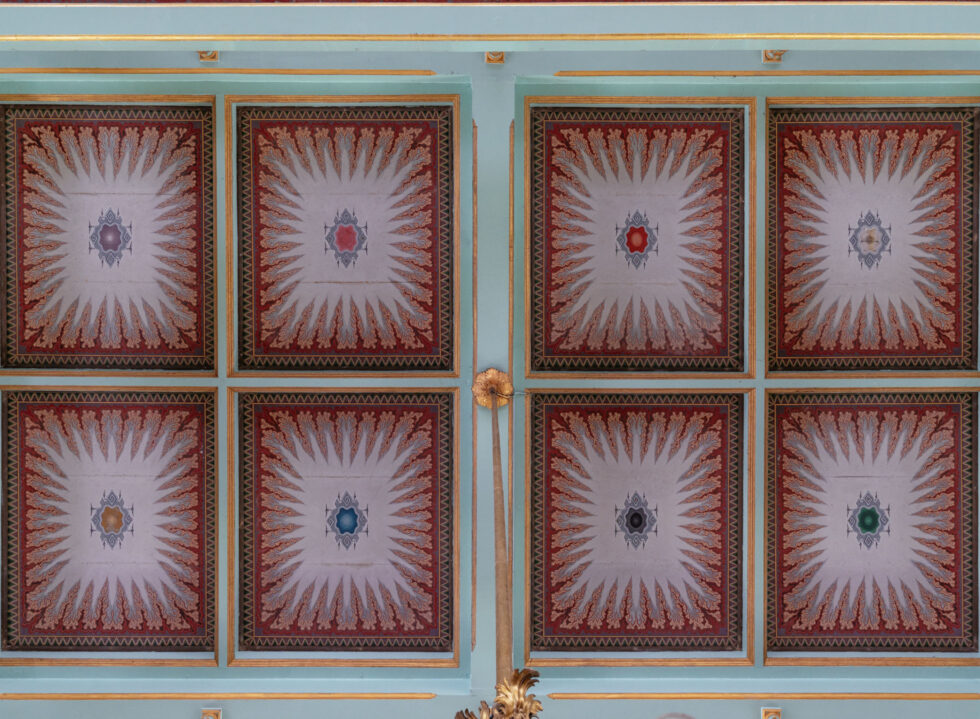

Today, her legacy continues. Once palace tours end on a Monday and Saturday afternoon, visitors are likely to encounter an open-for-all dance workshop carried out regularly under the painted ceiling of the Pendapha Ageng. The workshop is part of the programmes executed by Kemantren Langenpraja, the cultural division under Puro Mangkunegaran tasked to preserve the dynasty’s artistic heritage including dances, music and performances.

“We want to grow while remaining contextual, to build on a Javanese culture that is rooted in values that have been developed over the past 266 years,” Kanjeng Gusti stated. Ultimately, his interest in ushering Mangkunegara to its new era is not only defined by contemporary ideals, as reflected in Pracima Tuin, but also by preserving and reigniting traditions that have come before him.

The combination of these preserved traditions and knowledge provides a needed counterbalance to all the fast-paced growth and changes that have been happening right outside Puro Mangkunegaran’s gates.

It’s easy to overlook long-established programmes like the palace tours, which might have remained relatively unchanged throughout the years, but it can be a good starting point for those with a casual interest in the story of Mangkunegara. After a stroll through the historic walls of Ndalem Ageng and the West quarters of Keputren—where one could spot interesting tidbits like old family photos, gorgeous batik cloths and Javanese-style stained glass windows while listening to historical drama narrated by the tour guide—the interest might end up not being so casual after all.

And when one has exhausted the Wikipedia pages, there’s the palace library, the Reksa Pustaka. First built in 1867 under the decree of Mangkunegara IV, it’s home to a treasure trove of historical archives of writings and photographs alike. Inside the calmness of the room, where time seems to have halted sometime in the past century, one could even find an 1860-published book on Javanese ethics that the fourth Mangkunegara prince himself authored, titled Serat Tripama.

The combination of these preserved traditions and knowledge provides a needed counterbalance to all the fast-paced growth and changes that have been happening right outside Puro Mangkunegaran’s gates. A few years ago, visitors from big cities like Jakarta would have described Solo as a sleepy town, but according to 2021 data, it has since been transformed into the most densely populated city in Central Java—and by a wide margin. Not to mention the upsurge of tourists recorded the following year.

In line with this sweeping interest, Puro Mangkunegaran as a cultural institution can stand as the foundation of the ever-growing city, acting as a gateway for those seeking to understand the city and its roots that are inseparable from the legacy of the dynasty.

The life of the palace

“Mangkunegara’s retainers figure as prominently in the diary as do his family. They were numerous and their professional tasks varied,” wrote Asian Studies professor Ann Kumar of Pangeran Sambernyawa’s reign in her book “Java and Modern Europe: Ambiguous Encounters” (1997).

From that moment on to this day, the abdi dalem are the ones who breathe life into the palace and preserve it throughout the years and generations, dedicating their lives to serving the Mangkunegara family, motivated by a sense of duty and purpose that they often pass down to their children. “As an abdi dalem, you can’t expect financial gratification or be overly ambitious. Blessings will come in different forms. It’s a lifelong dedication,” explained Ibu Endang.

Their crucial role in the principality is something that Kanjeng Gusti Mangkunegara X recognises. Reflected in the photographs he documented on his personal Instagram account, these figures smiled openly to the prince behind the lens, as he credited their day-to-day contributions at the palace.

“We very much welcome [the new developments]. There’s like a new life at the palace,” remarked Ibu Endang when asked about the abdi dalem’s response to the revitalisation of Pracima Tuin, which brings many new faces into the palace staff. But for the retainers, it’s not the only thing that has changed since Mangkunegara X’s ascension to his princely role.

“There’s like a new life at the palace.” Ibu Endang, an abdi dalem working in the toursim division.

The previous Friday night at the Pendapha Ageng, a party was held for the abdi dalem in the event of the principality’s anniversary. Kanjeng Gusti’s older sister, Sri Sura, mingled alongside them. Some even felt personally close enough to her to tease her a bit about skipping the buffet. Her mother soon joined in, and the two could be seen exchanging warm chit-chats with the retainer families.

Before that night, according to one staff member in the palace’s development team, the celebration was something that had long been put on hiatus at Puro Mangkunegaran. Kanjeng Gusti decided to revive it. “Everything that I do here is for the family, relatives and abdi dalem who have served and contributed towards Mangkunegara over the years,” divulged the prince.

Since the passing of his father and the coronation that followed, Kanjeng Gusti has been swiftly shoved into new, immense responsibility. It could’ve been overwhelming, but he welcomes the challenge as something that he was born to do. “To me, taking care of Mangkunegara and its cultures is the same as me taking care of Romo, just as taking care of my ancestors’ heirlooms is like taking care of my grandparents. As a successor and a son, being able to take care of them all, it’s something that I’m willing to do happily.”