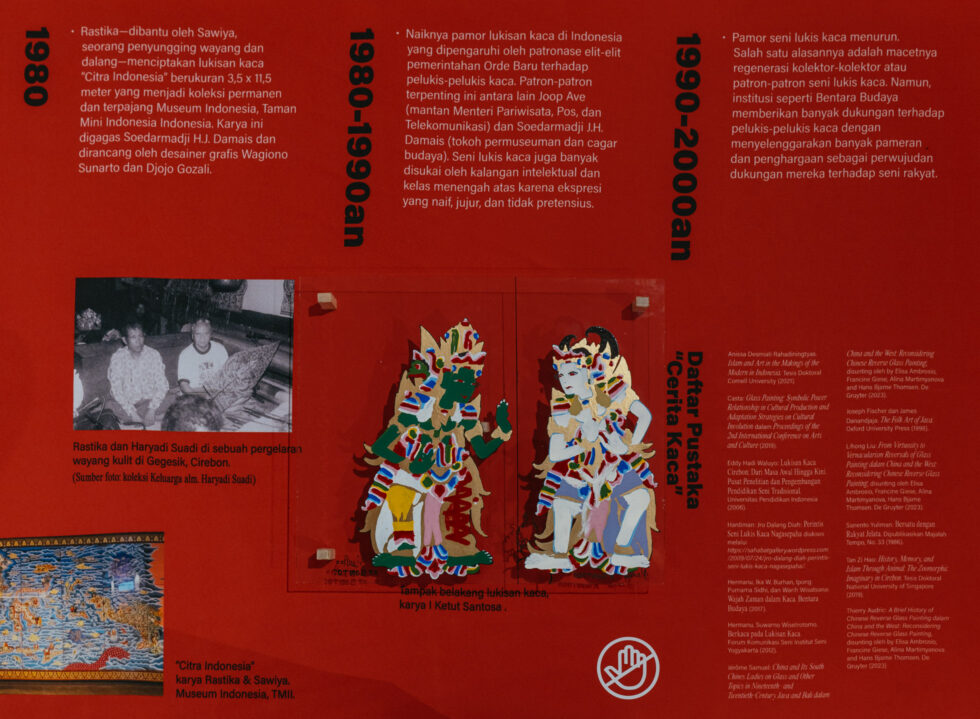

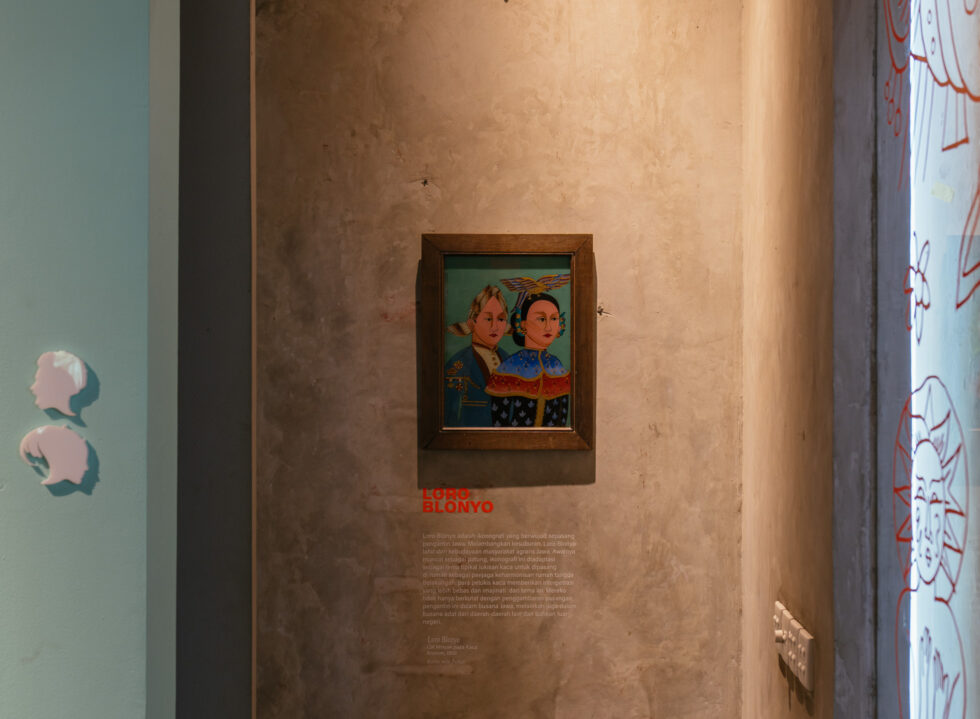

A degree of nostalgia fills every corner of ‘Cerita Kaca: Perjalanan Seni Lukis Kaca Indonesia’, an exhibition at Dia.Lo.Gue artspace that reflects on the forgotten art medium of reverse glass painting. Tracing back to its origin in 1300s Europe to its arrival in 19th-century Batavia via the Tiongkok trade, the exhibition digs deep into the assimilation of cultures and styles across the decades, placing emphasis on the absorption of Indonesian customs and traditions.

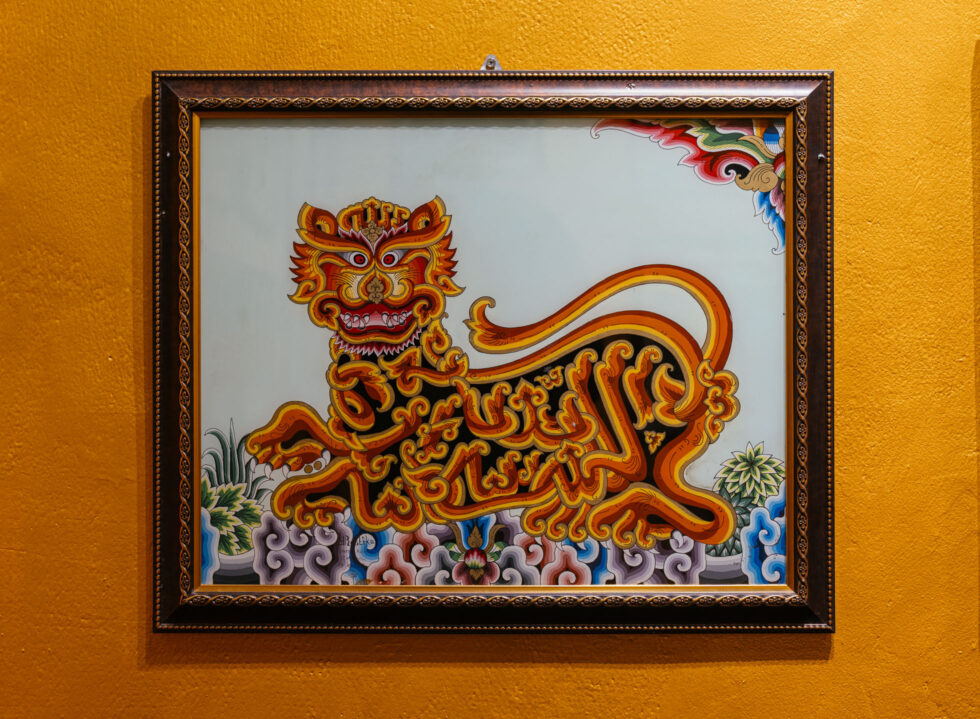

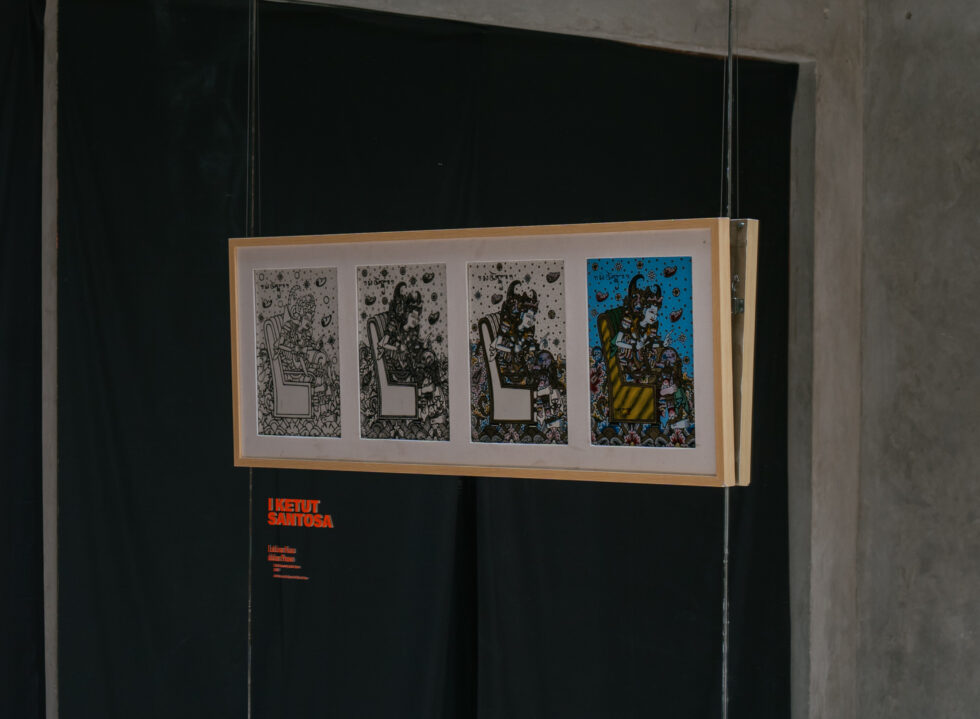

Like most artworks produced before the ‘80s, the purpose of the paintings was to “document and make sense of what was going on at the time,” shared co-curator Hermawan Tanzil. More than expressions of the characters and regional markers like the mega mendung pattern from Cirebon and illustrations of Buraq, the magical horse in Islamic traditions, a closer look at the paintings also reveals the methodical sequence in which they are assembled. Done on the backside of the glass, the technique dictates a reversal of steps, where the first layer begins with the finishing touches before moving on to the rest of the composition and background.

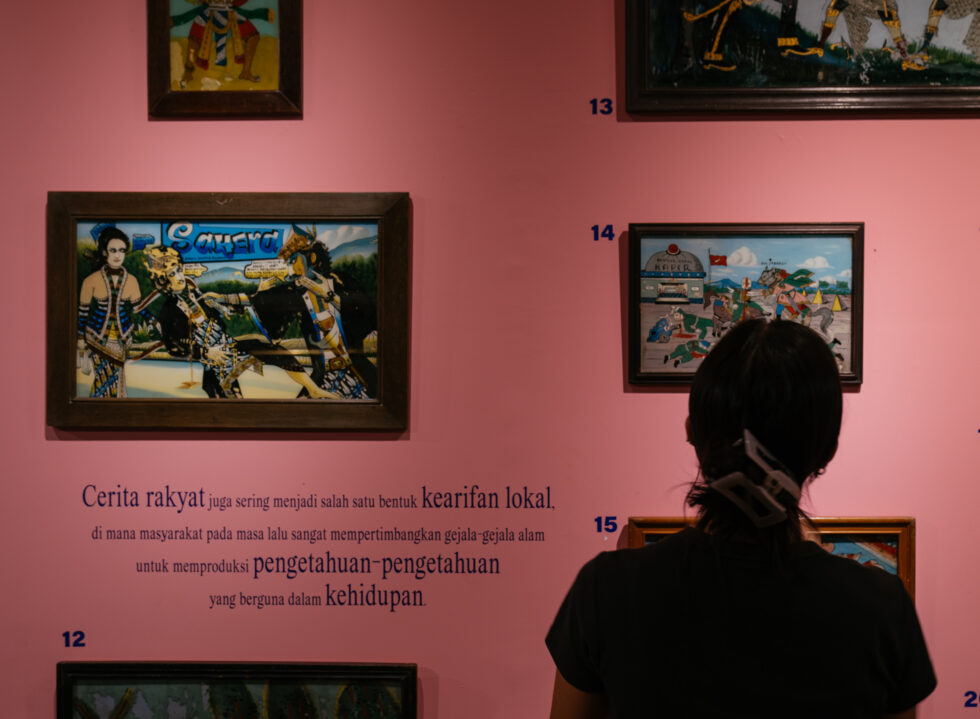

Adopting a spectrum of themes, some of the paintings elaborate on passed-down folklore and symbolisms like the wayang and Ramayana epic, while others are layered with anti-colonialism sentiments and socio-political currents conveyed with a hint of humour. Such is the case in artist Ning Istiariningsih’s ‘Wong Jawa Ilang Jawane II (Orang Jawa Kehilangan Kejawaannya) (2003), which depicts a scene of a woman in a batik-patterned bikini top and sarong, taking a photograph of a group inside a car, its licence plate reads ‘CIA’—a comic-like critique of how Javanese people are slowly losing their identity in favour of a more Western way of life.

“It was important for us to portray glass art as a malleable medium that transcends any particular time frame; traditional and contemporary at the same time, it reflects the mosaic of influences and styles that the medium has absorbed over the years,” Hermawan explained.

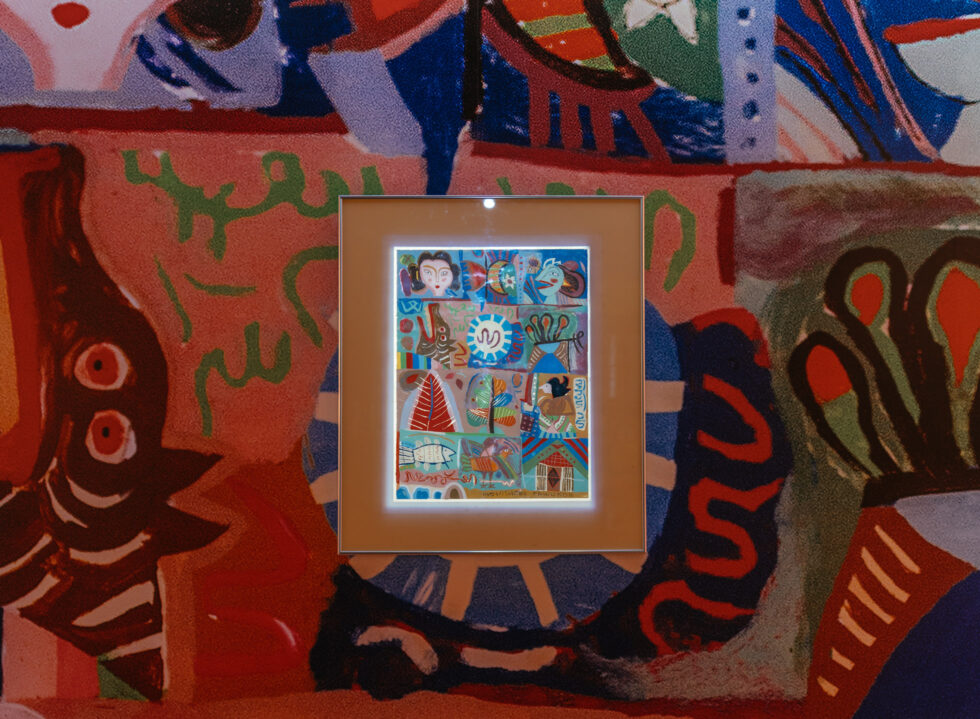

Towards the back of the space, encased in a glass room are works by the late artist Haryadi Suadi. Treading the fine balance between the traditional and contemporary, the artist reinterprets Arabic calligraphies and wayang features in a modern light with his use of organic shapes and a more vibrant palette. A fitting conclusion to the exhibition, the room leaves visitors to ponder how the medium would continue to evolve if given the right platform.

“We want to show people the historical and ongoing relevance of glass art, and remind them that they belong to the modern genre as well. It doesn’t have to be a dying art form,” Hermawan added.