In Southeast Asia’s bartending scene, Brendon Khoo and Mirwansyah ‘Bule’ are names with presence and influence.

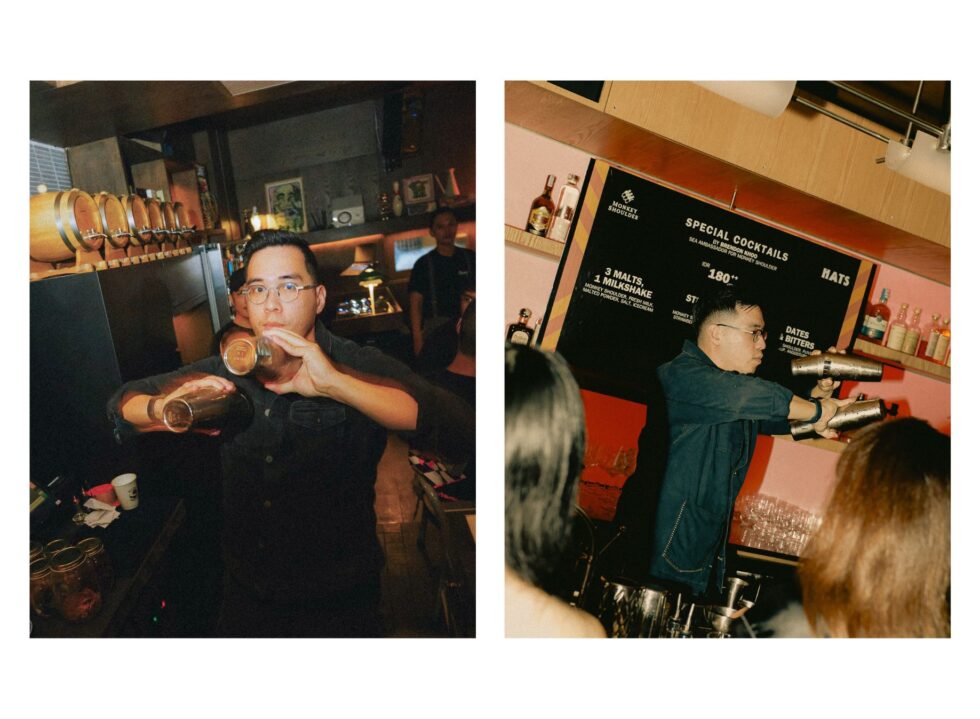

Originally from Kuala Lumpur, Brendon built his career behind the bar at several of Singapore’s most notable establishments. Today, he serves as Southeast Asia Brand Ambassador for Monkey Shoulder, the award-winning blended Scotch, championing a playful and straightforward approach to whisky cocktails while forging connections with bartenders and drinkers across the region.

In Jakarta, Bule is recognised as one of the pioneers in the city’s cocktail scene. Now Head Bartender at Modernhaus, he applies his time-honed, ingredient-first approach at the mid-century-styled cocktail joint, which impressively ranked #12 and was named the best bar in Indonesia by Asia’s 50 Best Bars 2025—all within its first year of operation.

In this exchange over Zoom, the two bartenders share their thoughts on the evolution of drinking culture, the challenges and opportunities facing the industry today, and how hospitality and connection remain at the heart of what they do.

This conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Brendon Khoo (BK): Hi Bule! To start things off, can I ask what your journey into cocktail making was like? I’m curious because I’ve always associated you with The Cocktail Club.

Mirwansyah ‘Bule’ (MB): My journey started quite a while ago, in 2007 to be exact, when I worked as a barback at a big club in Jakarta called X2. I left in 2010 and bounced around, working at restaurants and small cafés. In 2011, I joined The Union Group for their UNION Plaza Senayan outlet.

The Cocktail Club is actually a pretty recent venture for Union; we only started in 2021. It might feel like we’ve been around longer because our team—me, Kiki, Erik and Upay—has been doing this with Union for quite some time, back when people weren’t really interested in cocktails like the Old Fashioned or Negroni. We helped build that market from the ground up.

I remember in 2012, when we invited Marian Beke from Nightjar in London. That was probably the first-ever guest shift in Jakarta. Now, a lot of bartenders who used to work for Union have gone on to open their own cocktail bars across the city, helping the scene grow even more.

BK: And you’re still with Union now with your bar Modernhaus. They should give you an award for having stayed for so long (laugh).

As for me, I’ve always wanted to work in F&B, but my dad—like many Asian parents—wasn’t convinced it was a stable career. We compromised, and I went to hospitality school. While doing my diploma, I joined an inter-college cocktail competition called Morning Cup. I didn’t win, but making it to the finals made me realise that I could make a career out of it.

The real push came from watching ‘Hey Bartender’ (2013). Every bartender I know has seen it, and watching it convinced me that I wanted to dive deeper into the bartending craft. But around those times, there weren’t many cocktail bars in Kuala Lumpur, and I knew that if I wanted to grow, I had to move to Singapore. Long story short, I finally landed a job at 28 HongKong Street, and like you with Union, it was a real eye-opener. Then I went on to work at Crackerjack, and after that at Operation Dagger.

What was it like in Jakarta? What were some of the challenges that you feel like you faced when you started out?

MB: The biggest challenge with Jakarta is that it’s a bottle-service market—that’s where the money comes from. We love serving bottles, but things can get a little wild when someone’s three or four bottles deep in one night.

BK: So would you say that because of this bottle culture, it’s been harder to push cocktails? Like, maybe people think, “Why spend on cocktails when I can just buy a bottle?”

MB: It used to be like that. But these days, I’m really loving how much people’s curiosity about cocktails has grown. Since The Cocktail Club opened, I’ve noticed guests becoming more knowledgeable—sometimes even asking for cocktails I’d never heard of before. Interest has definitely gone up. Just last week at Modernhaus, we sold around 1,000 cocktails in one night. Granted, we were selling them at a fraction of the price to celebrate our placement in Asia’s 50 Best Bars, but still, it shows the shift.

“I try not to get overly philosophical with cocktails. Don’t get me wrong, I love hearing about concepts, but I’ve realised the drinks need to land well first. That opens the door for other things.” – Brendon Khoo

BK: Congratulations, by the way, for Modernhaus’ debut on Asia’s 50 Best Bars!

Anyway, talking about drinking culture, I feel really lucky to have joined Singapore’s scene when it was at its peak. Craft spirits were booming. When I was at 28 HongKong Street, I was suddenly surrounded by bottles and brands I’d never even heard of—each with its own story. People were genuinely interested in them, too.

At first, the challenge for me was feeling like I had to learn everything about every spirit out there. Eventually, I realised not everyone cares about everything, and it’s more about figuring out what kind of bartender you want to be. When I first started, I thought I’d go into flair or straight-up mixology, but I didn’t even realise there were so many other avenues—like specialising in flavours, or in creating great bar atmospheres through design. You become more well-rounded over time, but when I was younger, I had no idea you could even go into things like brand ambassadorship.

MB: I’ve been hearing that Singapore’s cocktail market is slowing down these days—is that really the case?

BK: Yeah, it’s been a tough time for a lot of bars. Rents continue to rise, landlords are less open to negotiating, ingredient costs have increased, and hiring new staff has become more challenging. On top of that, people just aren’t going out as much. It’s hard to blame them—post-COVID, there’s definitely been a shift in consumer habits.

I still remember visiting Jakarta as a Monkey Shoulder ambassador for the first time and going to H Club on a Monday night. I was shocked—it wasn’t packed, but it was still fairly busy. Compare that to a Monday night in Singapore, where most clubs are completely quiet. Right now, it’s really about riding out the storm, but it’s sad to see so many bars closing or going on indefinite hiatus.

MB: Do the local people not go out much?

BK: Not as often as before. A big part of it is distance—many people live further away, so going out isn’t just about paying for drinks, it’s the whole cost of the night. Cocktails in Singapore aren’t cheap, and getting home late can be just as expensive, especially with no late-night public transport and high taxi fares. All that adds up, so people tend to limit how often they go out.

MB: I guess we’re pretty lucky here. Transportation is affordable, and our local market is strong, so we’re not dependent on tourism, like with Bali, for example.

BK: Singapore’s also partly dependent on tourism, and it’s been tricky. I think Jakarta’s advantage is having a dominant local market with real spending power. Anyway, on a lighter note—Bule, can you tell me a little more about your approach to cocktail-making?

MB: I love working with local ingredients because Indonesia has so many. Take daun pohpohan, for example. You can’t find it in Singapore or Malaysia; it’s uniquely Indonesian. The challenge comes when I have to bring cocktails out of Jakarta. The leaves are so delicate that they spoil easily.

But as bars and methods have developed, we’ve found ways to recreate the flavour of fresh produce without actually using it—fermentation being one of them—making it easier to manage while keeping the same character in the drink. That’s also what you were doing at Operation Dagger, right? I was influenced a lot by [the founder] Luke Whearty and how he approaches cocktails. He’s very amazing; very clever.

BK: I would say Operation Dagger was a turning point for me as well. Have you had a chance to visit his bar in Melbourne yet? You would love it. They have this drink called ‘Speed Bump’, it’s local vodka made from milk and mixed with macadamia distillate, served ice cold with a ‘bump’ of soy-cured local ikura. It’s only a tiny glass, but it’s one of those drinks that makes you go, “Wow.”

It’s like Operation Dagger’s ‘Hot & Cold’, which is tequila infused with pineapple and lavender, shaken with more pineapple, lime and agave nectar, and topped with warm white chocolate foam. A lot of people didn’t even realise it had tequila. If you want the recipe, I can give it to you. Luke was always open with them; his mentality is, “You can take my recipe, I’m already working on more.”

“I’m really loving how much people’s curiosity about cocktails has grown. Since The Cocktail Club opened, I’ve noticed guests becoming more knowledgeable—sometimes even asking for cocktails I’d never heard of before.” – Mirwansyah ‘Bule’

MB: I’m curious, now that you’re a brand ambassador for Monkey Shoulder, how do you carry forward those modern techniques you picked up at Operation Dagger? Do you adapt them into a simpler approach, or find new ways to mix them into what you do now?

BK: That’s a good question. I’d say I adapt depending on where I’m doing the guest shift. If I know the bar is well-equipped, I might do clarified milk punches or foams—but nothing too out there, because Monkey Shoulder is all about having fun with whisky. I try not to get overly philosophical with cocktails. Don’t get me wrong, I love hearing about concepts, but I’ve realised the drinks need to land well first. That opens the door for other things. So more than technique, what’s carried with me is hospitality—and working with the bar itself.

When I joined Monkey Shoulder, I realised I don’t have my own bar, so I’m stepping into someone else’s space. The team’s perception is just as important as the guest’s because I’m only there for a night. So the question becomes: how can I make their evening more fun?

What’s your approach to coming up with new cocktails? Do you start with the concept first and then the flavours, or do you go the opposite way?

MB: I go the opposite way. I don’t start with the philosophy behind the drink. I focus on building the flavours first and figuring out how they work together. Starting with the philosophy and story feels counterintuitive; it’s more complicated to translate those ideas into flavours. So I’d rather get the taste right first, and then create the story around it afterwards.

BK: That’s actually really smart. I’ve realised over the years that some guests can tell when you’re forcing a cocktail to fit a story.

With Monkey Shoulder, I’m mostly working with one spirit, so the real fun is figuring out how to make flavours blend well with it.

One I’ve been serving a lot is Strawberries & Cream, because that’s exactly what it tastes like. It’s basically a whisky sour with Monkey Shoulder and strawberry jam, topped with soda for a fizz, then finished with a mascarpone cheese foam. In cocktail terms, it’s pretty simple, but I like reintroducing people to fun, direct flavours.

I’m not working at a bar anymore, and I don’t claim to be a top innovator of flavours. That’s what cocktail giants like you, Bule, have committed your careers to doing. I take a simpler approach, getting people excited about cocktails in the hope they eventually make their way to your doors.

“The challenge for me was feeling like I had to learn everything about every spirit out there. Eventually, I realised not everyone cares about everything, and it’s more about figuring out what kind of bartender you want to be.” – Brendon Khoo

MB: I mean, yeah, with guest shifts, people would be expecting a fun night. The cocktail itself almost comes second. When you’re behind the bar in different cities across Southeast Asia, do you notice any shared cultural traits between the countries or their people?

BK: I’d say food. Everyone has a signature dish that represents where they’re from. Having travelled to five different cities in Southeast Asia, I’ve found that food is one of the most powerful ways to share your culture. You can go to bars and see similarities, but food really brings people together.

MB: Yeah, I think so too. When connecting with the customers—or any stranger, for that matter—I’ve found that the easiest way is through food. It’s just more natural.

BK: Speaking of, do you find that the culinary scene in Jakarta intersects with the drinking scene there?

MB: I would say so. After a night of drinking, people always look for something to eat. Late-night eats are a big thing here, so in a way we’re riding on the culinary scene. For example, have you been to Nasi Gentong Mas? It’s an East Javanese food stall that opened in SCBD. People like to flock there after a night out, and it’s always packed. How is it in Singapore?

BK: At one point, Singapore’s culinary scene was dominated by Michelin-star restaurants and fine dining. That mindset spilled over into the cocktail world. There was this unspoken expectation—whether from consumers or self-imposed by bartenders—that cocktails also had to be cutting-edge. Suddenly, everyone wanted a rotovap, centrifuge, sonic infuser, and all those tools; because all that equipment was available here, it shaped how people approached drinks. But unlike Indonesia, we don’t have a farm-to-table culture or much in the way of local ingredients for cocktails.

Switching gears a bit—you’re now sitting in Modernhaus, which has been titled by Asia’s 50 Best Bars as the best bar in Indonesia this year. And part of what makes me so excited about visiting Modernhaus is the ambience that makes it look like a living room; emphasis on the word living, where it’s open and everyone can talk to each other. Why do you think design and atmosphere play such a big role in setting the tone and defining a bar’s identity?

MB: You start with the design, then the ambience, then the identity—they’re all connected. If you have a great design but can’t create the right ambience, it’s nothing. The bar’s identity needs to grow from both, so people can understand the concept and the story behind it. Everything has to flow together.

BK: Yeah, I agree. I’ve seen bars where the interior looks stunning, but when it comes to the bar layout itself, it’s just not functional.

MB: Exactly. Even if the design and layout are great, if the ambience is off, it can feel empty. No one’s talking to each other, and each table feels isolated from the next one. Some time ago, a member of The Union Group’s board of directors asked me, “If you were to have your own bar, what would it be like?” I told him I wanted to do something like an open-plan bar, where everyone gathers around the centre, very intimate, and there’s no barrier between the bartender and the customers. So, that’s what’s happening right now with Modernhaus.

BK: Would you say there are now more expectations of bartenders? Say, if someone isn’t part of the scene but hears this [Modernhaus] is the best bar in Indonesia, do they expect the ultimate hospitality or experience, or is it still not too different from before?

MB: At Modernhaus, expectations have definitely gone up since making Asia’s 50 Best. People now come for not just great cocktails, but a certain level of experience.

There’s also the expectation to accommodate more guests and have more people try our drinks. We saw that with The Cocktail Club when it made the [Asia’s 50 Best] list—it became a high-volume bar drawing a wave of curious visitors. But that’s not the direction we want for Modernhaus. We keep the focus on the intimate experience, which means we can’t fill the room to capacity. The guest flow has to stay slower and more deliberate.

“If you have a great design but can’t create the right ambience, it’s nothing. The bar’s identity needs to grow from both, so people can understand the concept and the story behind it. Everything has to flow together.” – Mirwansyah ‘Bule’

BK: I guess guests now are also more aware of what kind of bar they’re visiting and the different experiences each one offers.

MB: Yes, guest behaviour is changing alongside the evolution of bar culture. On that note, from your perspective of working under a brand, what are your thoughts on the future of the cocktail scene?

BK: I think it’s going to be a very challenging time. I’m just being real. Obviously, everyone wants to stay optimistic and talk about exponential growth over the next few years, but the reality is we’re at a stage where we’re starting to see exactly what people are looking for, and it comes in waves.

Hospitality will always be there, so I think the future still looks good, but what’s important now is to focus on building the next generation of bartenders. When I started, there were lots of events and opportunities to meet people, which helped you attach your name to a bar and build your brand. I see the same potential in Jakarta, but young bartenders need good mentors. The future is bright, but we need to ride out the storm. Any thoughts from you, Bule?

MB: I share your thoughts. I think it’s going to be good. Right now [in Jakarta], our generation is already focusing on developing the next generation of bartenders. We know what to do and what to create, but ultimately, whether the cocktail scene will continue to thrive or not depends on them. From the cocktail side, what flavours or methods do you think will be popular next?

BK: I’ve been noticing how fashion trends from the ‘80s are making a comeback. I think cocktails will follow a similar cycle. We’ll always have the mainstays, but what’s ‘hot’ will come back around again, often in a reimagined way.

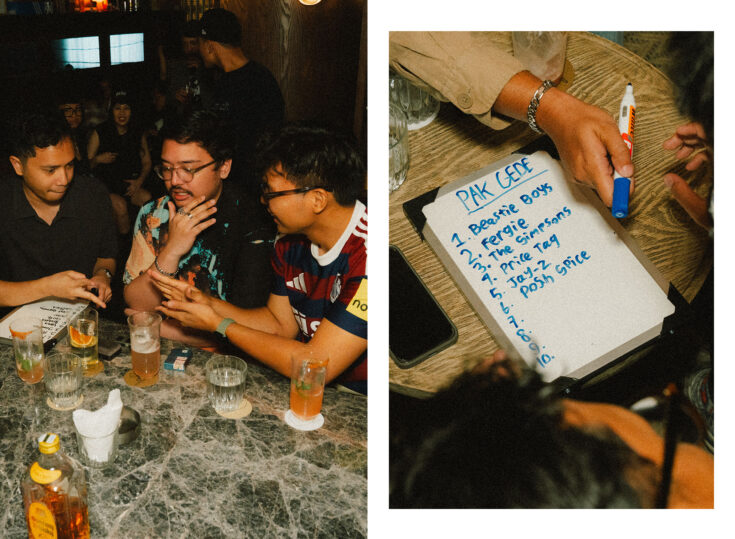

MB: Yeah, exactly. I remember the last time I visited 28 HongKong Street, they were doing these disco-era drinks like Long Island Iced Tea. We’re doing something similar at The Cocktail Club right now. Our Zombie, for example, sells around 150 glasses a night. We add our own twist, of course, adapting it to today’s market.

BK: So maybe it’s like—to know where you’re going, you need to know where you’ve been. Speaking of which, do you think the drinking culture there can evolve into something beyond just alcohol? Could it become a reflection of Jakarta itself, for example, and its culture?

MB: Honestly, I’m not sure the drinking culture is widespread enough for that. Indonesia’s a Muslim-majority country, and a lot of young people today don’t even drink. Many prefer sports or other wellness activities. Jakarta is not like Bali, where beer culture is huge.

BK: I get that, but I also think Jakarta’s drinking culture has already evolved beyond alcohol itself. Yes, it’s a Muslim-majority city, but that hasn’t stopped people from going out. At its core, it’s still about connection—and in many ways, I feel that sense of togetherness even more strongly there than in Bali.

MB: That’s true. In Jakarta, drinking culture often becomes a way for people to connect. But I was thinking more in the sense that it’s not as ingrained. It’s not like you’d see people casually day-drinking a spritz, for example.

BK: Right. It’s hard to say what a culture truly reflects when it isn’t as common or visible.

MB: Still, it’s something we’re trying to tap into—shifting people’s mindset about day-drinking. Who knows, maybe one day it’ll be more widely accepted.

BK: Yes, who knows? Anyway, thank you so much, Bule, for the conversation! I hope I get to visit you at Modernhaus.

MB: Likewise, Brendon. I’ll see if I can make it to your guest shift tonight in Blok M!