Prior to 2019, hum-drums of a new capital city for Indonesia circulated. Last year, President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo confirmed that one of the biggest national undertakings in the country is finally happening: the relocation of the Indonesian capital city of Jakarta to some 1000 km away to East Kalimantan was in the agenda. Unsurprisingly, the news was received with reactions that ranged from utterly supportive, indifferent to downright pessimistic.

The relocation is motivated by numerous considerations including the ecologically deteriorating state of Jakarta, overpopulation and much-needed shift of attention to other parts of our large archipelago, among others. Independent of how the public views this gargantuan project, the administration has gone forth to find the candidates that can bring this vision of a city reflective of its prized national values into reality through the official Sayembara Desain Ibu Kota Negara, a countrywide competition for the design of the new Ibu Kota Negara (national capital city or Ibu Kota for short).

Among the hundreds of entries, one local firm emerged as the winner: URBAN+ headed by urban designer Sibarani Sofian was entrusted with the once in a lifetime project to build Indonesia its soon-to-be new capital city. Manual Jakarta spoke with Sibarani to understand the process and depths of this massive and great opportunity.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Manual Jakarta: We heard a great deal about the relocation of the new Ibu Kota, and with this, you and URBAN+ surface a lot. How did it start?

Sibarani Sofian: We knew about the relocation of the capital city probably since early last year. The moment we heard President Jokowi announce it, everybody, especially us in the design community, got excited. Ibu Kota is going to be a brand-new city, and our company works on that scale—specialising in urban design and planning. We were confident we’d be among the candidates with good potential to win the sayembara (competition), or at least to be shortlisted. We didn’t know whether the shortlist would consist of fifty or thirty, but apparently it was only five and we won.

MJ: How did you approach the project for the competition?

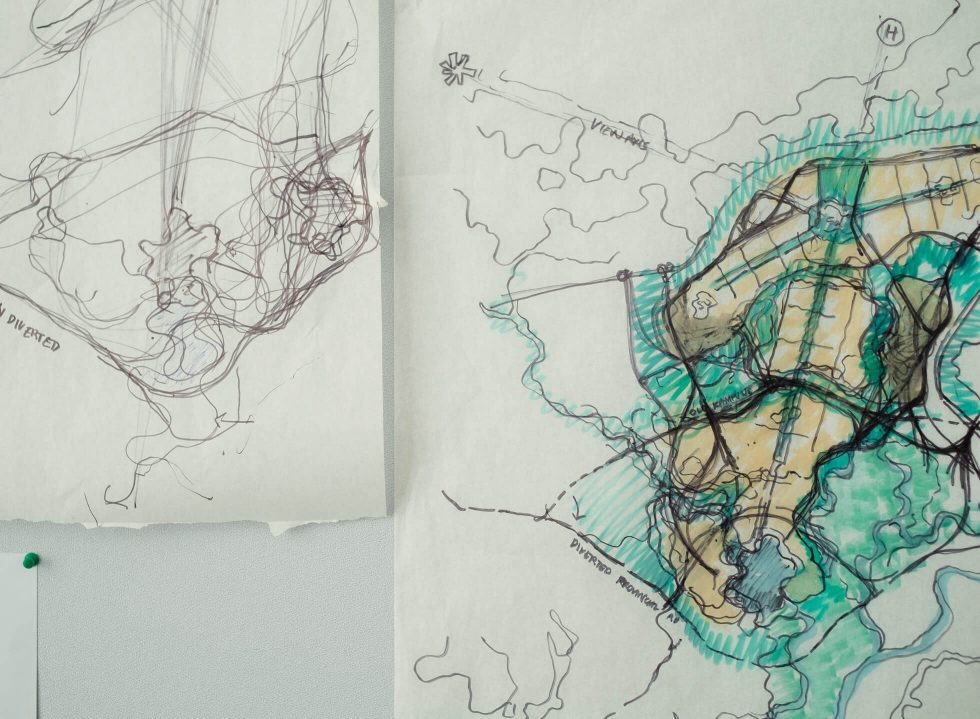

SS: We referred to the TOR, which stands for Terms of Reference. This document is the rules of the competition. The TOR is already set so it’s now up to how designers respond to it. Give us the gist, and we can just cook it. So when we got the second TOR, we started to see: “Okay. This is going to be green, smart, beautiful and international.” It means we want to flex our power to the world, but at the same time we want to be inclusive of Indonesia’s diversity and values while being in Kalimantan. We weren’t just designing buildings in a capital city, we’re talking about a whole metropole of 250,000 hectares. That is equivalent to Jakarta, South Tangerang, Bekasi, Depok and Cibubur. The core area or the main urban area is 60.000 hectares. The TOR came in October, and we had to finish and submit by the end of November.

MJ: And what was URBAN+’s take on the TOR?

With Kalimantan, we are entering into an image of ‘virgin’ state of an island, one that we tend to destroy. I thought we needed an approach that will be able to answer that kind of negativity, a narrative that isn’t about destruction but one that improves it. Secondly, this is also a city of Indonesian pride, right? And third, we must talk about the future. So, that’s why we came up with the phrase ‘Nagara Rimba Nusa’. Nagara is the representation of the government. Rimba is for Kalimantan that is known for its nature, and Nusa is a philosophical notion that all Indonesians are part of the Nusa. It may sound just like a song name, but it represents the city, nature and identity of us Indonesians. From this concept, we’ve derived three deeper intentions: First, the ecological and environmental message. The second one is the international standard for which we’re embarking on. And third is the expression of pride as Indonesians, or ‘Indonesia-sentris’ as Pak Jokowi said.

MJ: So how do you go about designing a city that embodies that philosophy?

SS: The city is an ecosystem of fractures or aspects: transportations, greenery, programmes or we call it ‘land usage’, pedestrians, energy, utility. It is a complex system that we have to cook into what you see as a ‘nice design of the city.’ If you look at the Nagara Rimba Nusa, it feels like it’s coming out of the jungle, it doesn’t look provoking nor threatening. We want it to be very humble and also very realistic. If I walk you through how we ended up with these clusters, we are doing very little to the forest and building on top of the existing, disturbed land, like ex-palm oil plantations. There, we put a city that goes back to our principles: world-class, environmentally friendly and inspired by Indonesia.

MJ: Geologically speaking, what will it be like to build a city on Kalimantan soil?

SS: Unlike the volcanic islands of Java, Sumatra and Sulawesi that are prone to tectonic issues, the challenges in Kalimantan will be water supply and soil conditions because the region for the new capital city in East Kalimantan is mostly peatland. We won’t be building on that, instead, we chose alluvial land—which also has its limitations to build vertically. I am not a geologist, but I was told that we cannot build high-rises. We won’t go past ten storeys, which is okay because we’re not envisioning Manhattan or Hong Kong. Then, Kalimantan has limitations on the main source of material it can provide for buildings, which is concrete. Concretes are made of stone and sand, and Kalimantan doesn’t have that. But then it has timbers. A lot of environmentalists will say, “Yeah, whatever. You’re still cutting the trees and destroying forests.” The short answer to that is, if we stop taking from the forest, why do we still have wood anyway? There is still no replacement for wood or timber. It’s still more recyclable than any other material and there’s an international standard on how to harvest timber, one of them is FSC (Forest Steward Council) imposed by the U.S. and EU, for all timber products, for which Indonesia is a major exporter. The certification is very strict with replanting programmes and environmental guidelines. With that assumption, if we already export good timber that we will not see to our benefit, we should be using that timber for our development. We could be using concrete if we bring it from Sulawesi or Java but that will add cost and will be even more environmentally damaging. If you want to be wise to build in Kalimantan with its soil condition, use timber.

MJ: And how about the water supply issue that you mentioned earlier?

SS: One of the possible solutions is to use rainwater before it flows into the river. Or if it’s in the river, we catch it before it enters the ocean, then treat the water in a treatment area to be filtered. It’s a tedious process and costly too, but at least it’s more environmentally responsible compared to desalination. There’s also another option to build a water dam, but that will increase the risk of flooding and devastating the surrounding flora and fauna, on top of being expensive. Additionally, the dam will need extreme elevation which Kalimantan does not have naturally. This is all a plan and we need to figure this out slowly. The dream is to build a reservoir for 2,8 million people, but for now, we estimate that river water will be enough to sustain a city of 500,000 people.

MJ: And realistically speaking, is the time frame you’ve been given…

SS: I cannot speak on behalf of the government, but speaking as an observer, on top of the challenging physical conditions in Kalimantan, the second issue is how we will work with the government. Either way, we will have to be fast, and to do so we have to work very quickly or have money to speed it up. We certainly don’t have the latter, which is why we need to work faster, more efficiently and coordinate better. Unfortunately, that is something that the government is not very good at. So realistically speaking, in five years, we can only build a few buildings, roads that lead to Ibu Kota and set electricity and water supply in some areas. And we also have a political timeline for the president—with four years left in the office, Pak Jokowi will want to see something.

MJ: Down the road, in what ways relocating the capital city will affect Jakarta?

SS: It will definitely impact Jakarta at some point, but I don’t think it will drastically change Jakarta. It will ease certain burdens of the government’s function. Such as traffic, security, etc. In fact, it will help Jakarta, especially during demonstrations. Jakarta will have some buildings and even blocks emptied. We have 34 ministries in this country, and there are about 50 to 80 state institutions, so there will be a lot of empty spaces. The government already tried to see the possibility of capitalising the land by offering it to the private [companies] to build and operate something. This is what we call ‘urban regeneration.’ In Europe, they often renovate old train stations into a plaza, like the Leipzig Plaza in Germany. We regenerate the city in the old areas and change the function of it. Urban regeneration is also supposed to benefit people who cannot live in the city. But we’ll have to see because if it’s not in the affordable pricing point for some people, it will only serve certain segments of the market or population.

MJ: I hope all the freed-up spaces won’t become malls…

SS: The government shouldn’t let this process go completely to the privates. At least maintain some social interest with this opportunity. I think a good 30% [of the freed slots] should be affordable: Put incentives to build public housing, for example. But to the business, it will go to whatever or whoever pays best. It’s a very capitalistic approach if the government doesn’t have the intervention to create a fairer [market].

MJ: A project of this scale must be a once in a lifetime opportunity for urban designers like you. What kind of importance is this highlighting for you and your community?

SS: My personal reflection is that this is a very good opportunity for us and also for raising people’s awareness about the importance of urban design. In my interpretation, urban designers bridge the gap between architecture and urban planning—we specialise on integrating the systems of the city when there are hundreds of buildings within a space and a government policy to follow. We call it ‘Design of The Public Realms.’ Take Jakarta, our malls are as good as the ones in Singapore. But step outside and would you say Jakarta is a good city? Architecture has limitations in responding to certain issues, while urban planning is like a doctor giving prescriptions—it’s not medicine. People like us, we try to design a better city. When I graduated with a degree in architecture from Bandung Institute of Technology, I took a risk by continuing my studies in urban design because the profession did not even exist here in 1997. Now I am more of an urban designer and that is where my passion is.

I think there were 1100 architects graduating every year in Indonesia, but we only have twenty to thirty urban designers every year. Today, there are 500 urban designers in the Association of Urban Designers in Indonesia; only 200 are actually practising. How can we even make it there? So, we really think that the sayembara and Ibu Kota will elevate our profession in the public eye, and I hope a lot of people will want to learn [urban design]. And we, as an association, will be ready to nurture, share knowledge and gather to create a network of city designers. Hopefully, we can contribute to a better city.