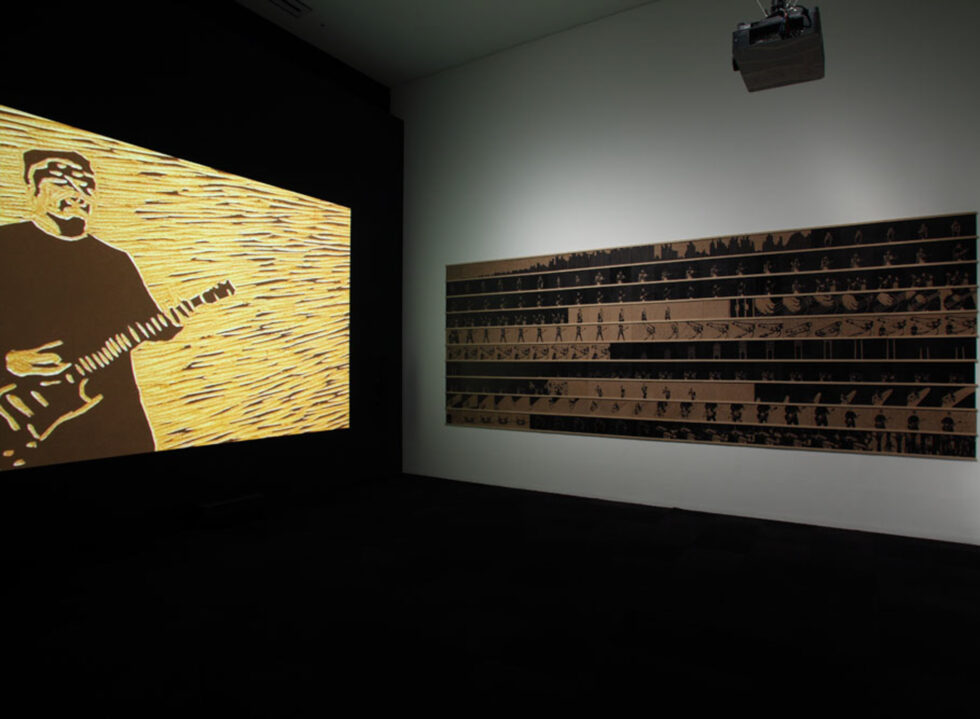

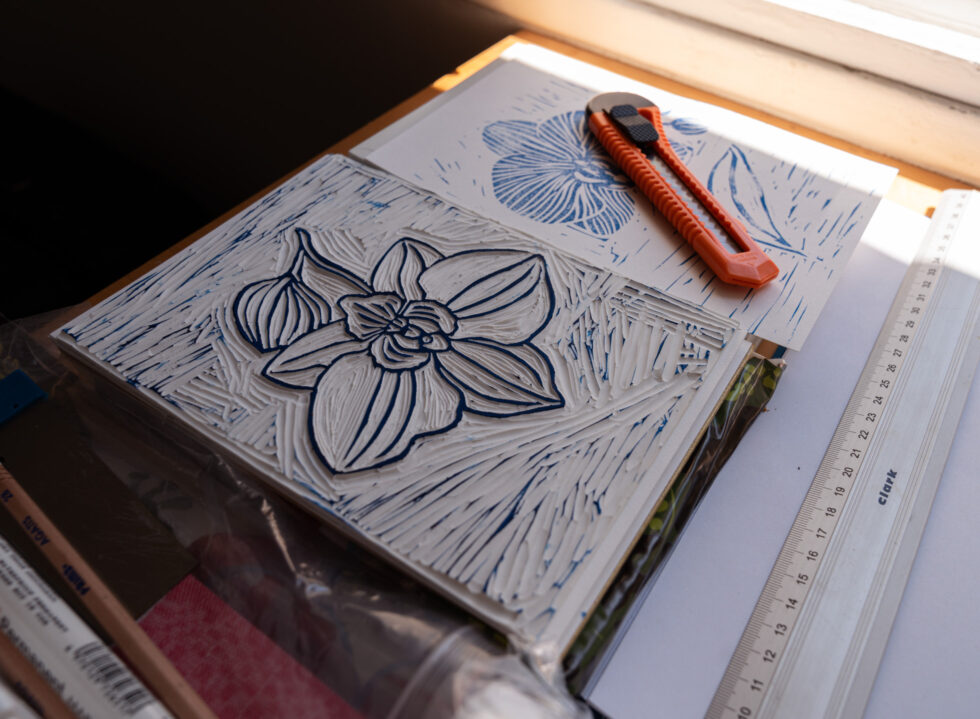

Tromarama’s first collaboration as a collective began in 2006 during a group-based music video workshop titled After School, where each team was paired with a local musician to create a visual interpretation of their work. Assigned to the heavy metal band Seringai, the trio spent nearly a month hand-carving 450 frames from A4-sized plywood, producing a rapid-fire stop-motion sequence that echoed the raw intensity of the band’s track, Serigala Militia.

“Back then, our generation was really into MTV as one of the main sources of music and visual inspiration. It felt like this exciting, refreshing thing, especially when MTV Indonesia started playing their own local programmes. That ended up being our first collaborative work. It was intense, physically exhausting and kind of traumatic, honestly. That’s actually where the name Tromarama comes from…trauma-rama,” shared Ruddy Hatumena.

Over the next two decades, Tromarama—composed of Ruddy, alongside Febie Babyrose and Herbert Hans—would evolve into a multidisciplinary practice defined by humour, tactility, and an ongoing engagement with Indonesia’s shifting media landscape. Their work spans stop-motion films, kinetic sculptures, immersive installations, and software-driven performance pieces—threaded together by a restless curiosity about material culture and the collapsing boundaries between the physical and virtual.

Much of their early work made use of everyday objects and humble materials, from buttons, tableware, textiles, to oil on canvas. An animation video might be constructed entirely from ceramic plates moving in choreographed succession; another might feature a hand-painted animation rendered directly onto canvas. This material playfulness has remained central to Tromarama’s practice, even as their engagement with digital technology has grown more complex.

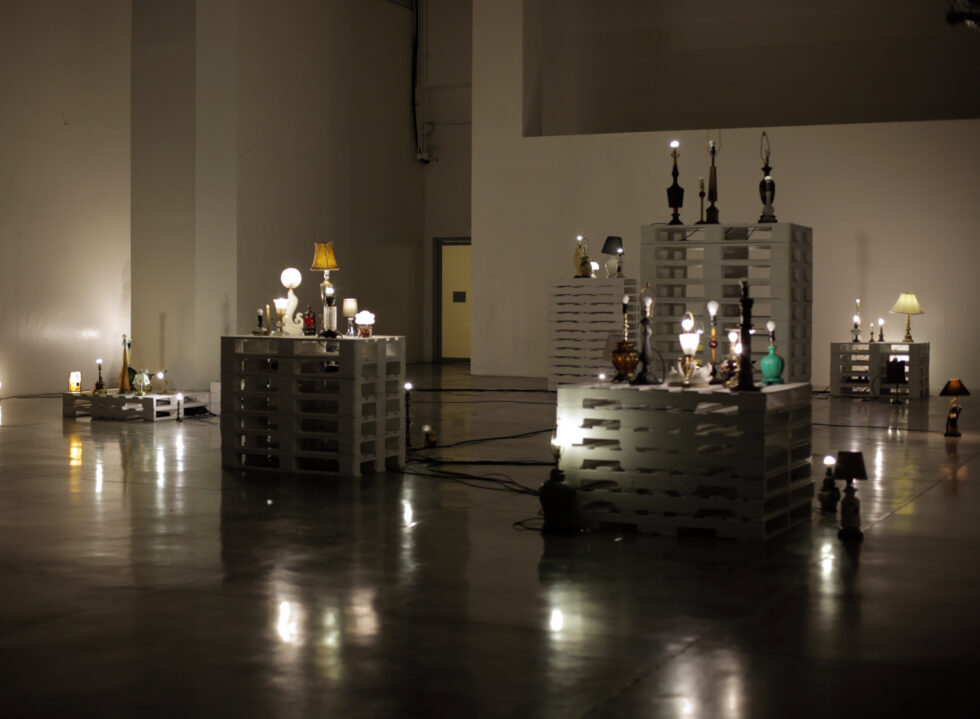

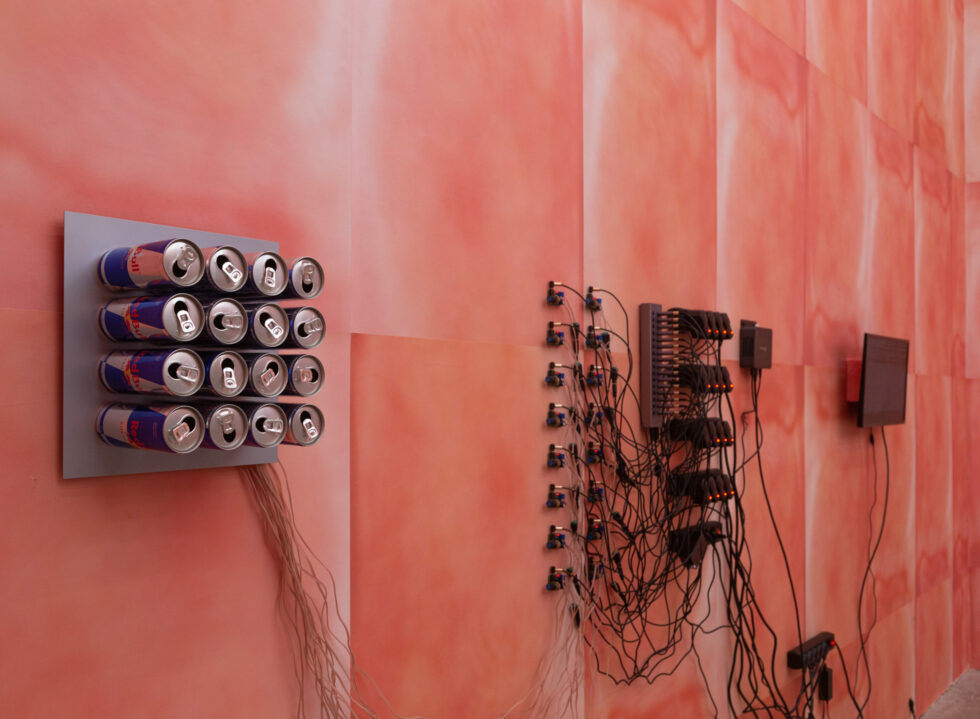

In more recent works, Tromarama has layered their material-focused approach with algorithmic logic and custom-built software, developed in collaboration with Tangerang-based Digital Nativ studio. ‘Soliloquy’ (2018/2022), which was first exhibited in Museum of Contemporary Art and Design in Manila, offers a striking example: the installation draws live user activity from Twitter to activate 96 vintage lamps sourced from a flea market. Each time the hashtag “#kinship” appears, the tweet is translated into binary code, which prompts the lamps to flicker, transforming ephemeral online gestures into a physical choreography.

“What does it mean to be human in all this? What’s our role, our function, in the midst of technological acceleration?” – Herbert Hans

“Why Twitter? For us, it’s a kind of landmark—a symbol of this era,” Herbert, fondly known as Ebet explained. “Before ’98, everything was filtered and tightly controlled. [With Twitter], suddenly people had the freedom to speak openly in public spaces. Even if that space is virtual, it still functions as a kind of public sphere.” While Tromarama’s early projects engaged with real-time data extracted from then Twitter (now X), they now exclusively use archived material when showing these pieces—a telling shift that mirrors their evolving relationship and stance on digital participation and institutional control.

This ongoing fascination with mediated reality, they note, traces back to a moment Ebet shared with his mother. She once showed him a hyper-realistic, computer-generated image of a war taking place in Indonesia, so convincing it looked like a photograph. “Over the past decade or so, we’ve increasingly experienced the world through its representations rather than through direct encounters,” Ebet reflects. “That creates a kind of spatial and temporal disorientation. It blurs our sense of time and place.”

Rather than viewing technology as something to fear or blindly embrace, Tromarama encourages us to interrogate, speculate and subvert these systems we’ve built and now come to depend on.

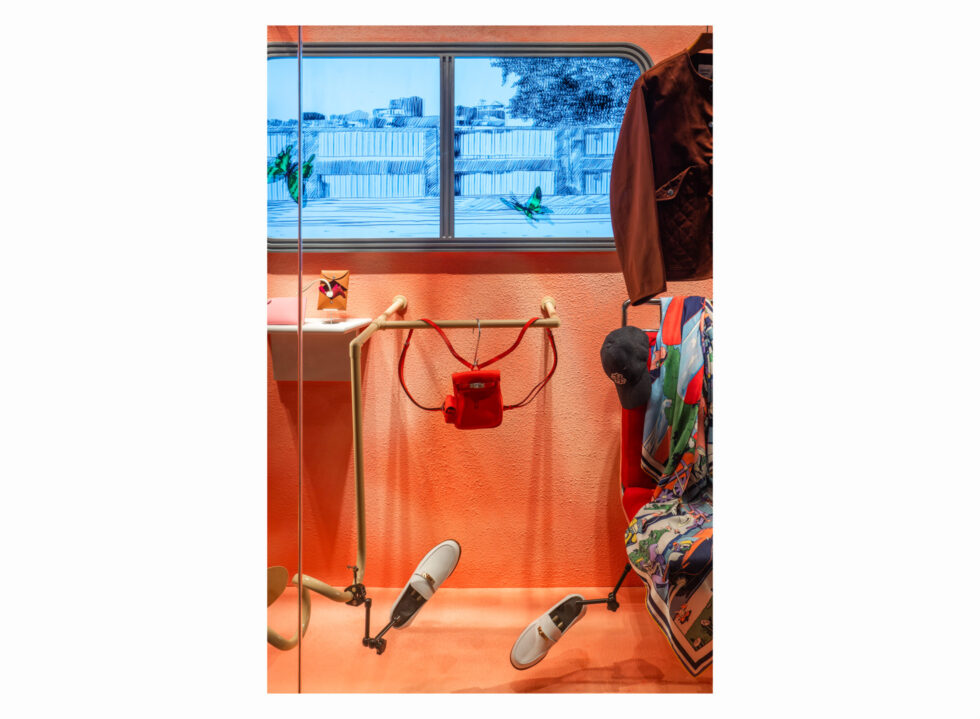

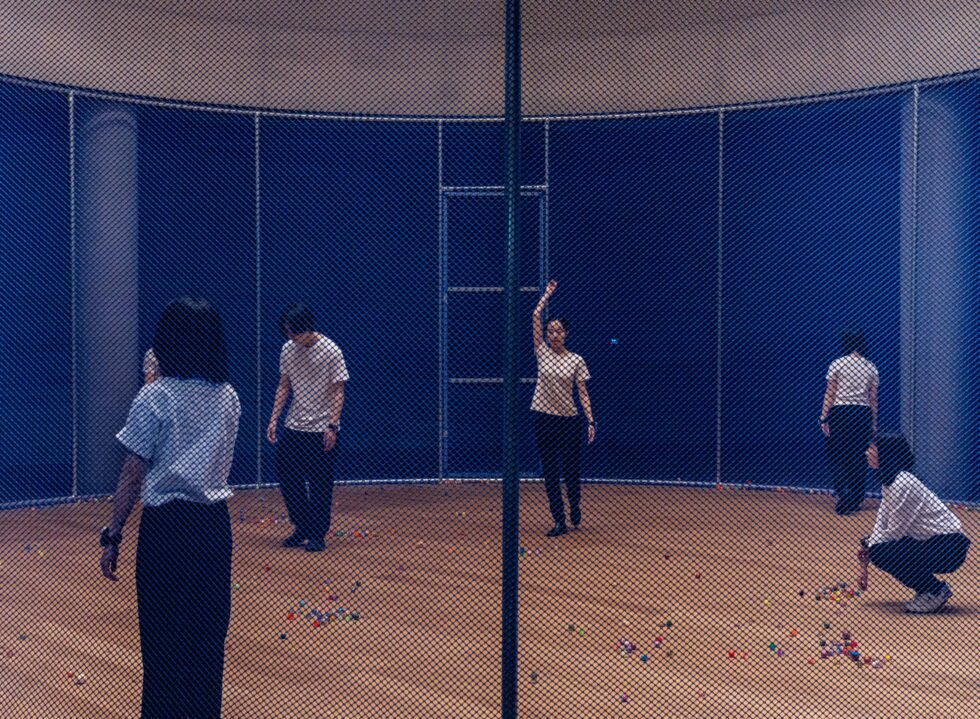

This dislocation between body and image, reality and representation, recurs throughout their work. ‘Banting Tulang’ (2021), for instance, explores the shifting nature of labour in a post-digital economy. Set inside a cylindrical structure of industrial blue mesh, the performance features eight “activators” wearing haptic devices on their wrists. Each time a tweet tagged #pleasure appears, the device vibrates—prompting them to throw bekel balls or seeds against the wall or floor in a repetitive motion. “At the core, the question we’re asking is really about agency,” says Ebet. “What does it mean to be human in all this? What’s our role, our function, in the midst of technological acceleration?”

These questions pulsed throughout Ping Inside the Noisy Giraffe, Tromarama’s first solo exhibition in Seoul, which took over all four floors of the SONGEUN Art Space earlier this year. The show traced their evolution from the raw energy of Serigala Militia to more recent works involving live performance, sensor technology, and ambient sound.

Among their newer works was ‘Purple Collar’ (2025), a playful but pointed sound installation composed of 32 musical instruments—melodicas, bar chimes, soprano recorders—each rigged with clamps to play musical notes pulled from Baby Shark, the hyper-viral children’s tune and cultural export of Seoul. As with many of their recent works, the instruments were triggered by social media activity, transforming scattered online signals into a synchronised chorus.

In recent years, this inquiry has taken on new urgency especially with the rise of Artificial Intelligence, prompting the artists to consider how creative authorship is being reshaped and challenged in the age of generative tools. “It’s a bit like when photography was first invented—many painters at the time likely saw it as a threat to their craft. Maybe our current unease with AI is part of that same cycle. Over time, we may come to see it not as something to fear, but simply as another tool,” reflected Ruddy.

“When used with clear intention, AI can actually become a way to critique technology itself.” – Ruddy Hatumena

Naturally, that coexistence isn’t without its tensions. Febie added, “It feels like we’re living through a kind of digital colonisation—coexisting with a new system like AI that’s reshaping how we create and interact. And for me, that’s exactly what makes it so compelling: the ongoing, unresolved question of authorship in the age of generative technology.”

Rather than viewing technology as something to fear or blindly embrace, Tromarama encourages us to interrogate, speculate and subvert these systems we’ve built and now come to depend on. “As much as we’re open to creating work that incorporates AI,” Ruddy added. “We’re still figuring out how to do it in a way that defies the typical AI aesthetic. And I think that’s the exciting part for us as artists, being able to play and question it through our works. And when used with clear intention, AI can actually become a way to critique technology itself.”