As a journalist navigating the intersections of business, technology and geopolitics in Southeast Asia for the past decade, Antonia Timmerman is firm in her belief that these sectors are far more intertwined in everyday life than we often realise. In particular, Antonia draws attention to the all-encompassing impact of technology and the accountability of its creators, where its influence can loom large and ferment in the public consciousness through the small acts of daily life.

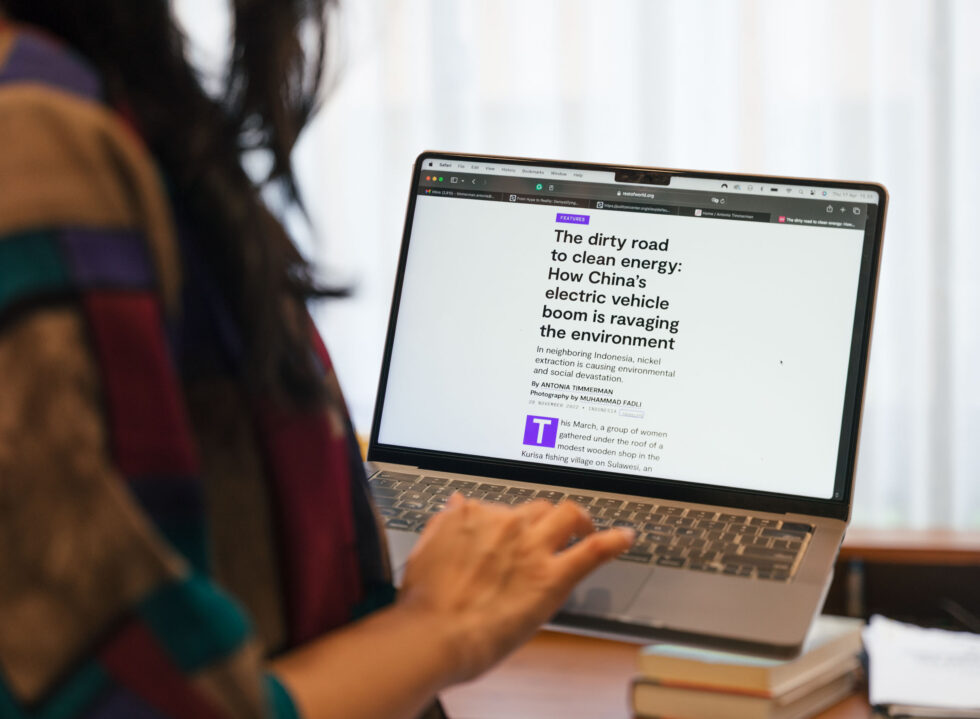

Digging deep into these themes, Antonia’s reporting has appeared in publications such as the South China Morning Post, VICE, Nikkei, The Diplomat, and Rest of World. Her in-depth coverage of Indonesia’s nickel and electric vehicle industries for Rest of World earned her accolades from SOPA (The Society of Publishers in Asia) and an honourable mention at the SABA 2022 Best in Business Awards.

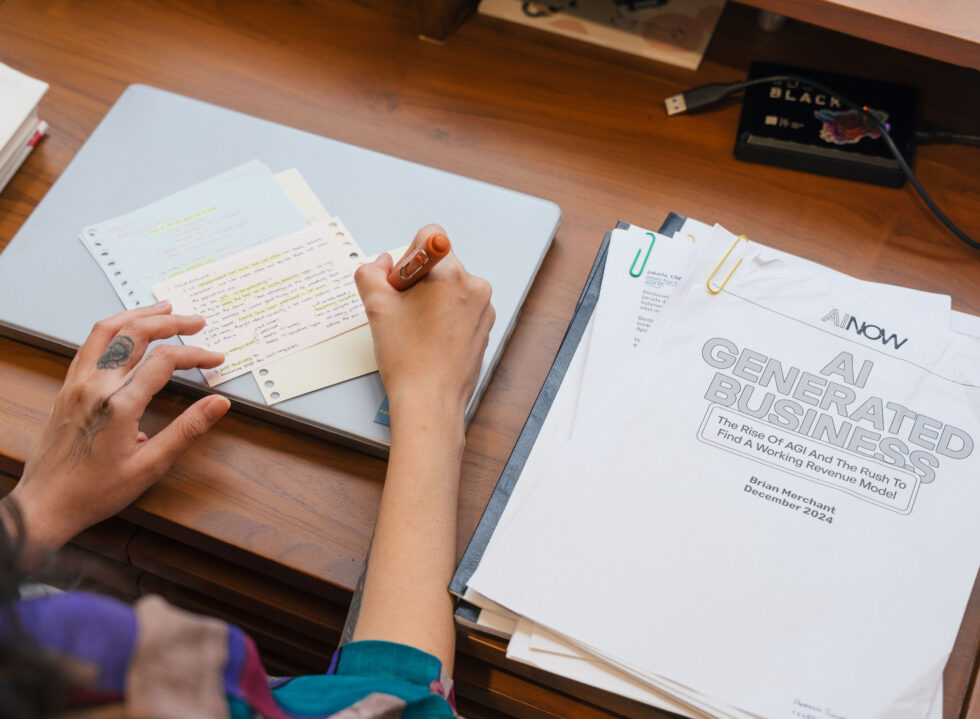

Today, Antonia splits her time between journalism and fiction writing, where she currently focuses her reporting on the rise of generative AI in Indonesia and its rippling effects on creative workers. We met Antonia at her apartment in Alam Sutera, where we broke into conversations about her longtime love for writing, the urgent call for ethical scrutiny in technology, and her observations on where the local media landscape is headed. This conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

MANUAL: A lot of your writing concentrates on business, technology and geopolitics. But before diving into that, what was your start in journalism?

Antonia Timmerman: I started in business journalism. Back in 2013, I began covering stock movements, IPO (initial public offerings), and M&A (mergers & acquisitions), so I stayed in that field for a while. Even as I moved across different media companies, I spent a lot of time covering finance, business, and, eventually, branched out to technology.

But over time, I got tired of it. I wanted to explore other things, so I tried to write independently. That’s when I started pitching to outlets like South China Morning Post, Nikkei, and Rest of World as a freelancer. That’s when I really began branching out to other topics, but still under the banner of the aforementioned themes.

M: Tracking back a little, did you study journalism formally? Have you always wanted to be a journalist?

A: I majored in Mass Communication at Limkokwing University in Malaysia. But writing has always been close to my heart, even from a young age. My mom used to read me storybooks, and I was always excited for more. And as soon as I could read, I was so eager to write, so I wrote everything: essays, poems, random gibberish—whatever I could.

As for journalism specifically, it was quite a natural progression. I think it’s partly because growing up, one of the most accessible reading materials we had at home was newspapers; they were affordable and arrived every day, so I grew up reading them regularly.

M: We’re curious about your profile on Deddy Corbuzier for Rest of World, where you talked about his YouTube show, “Shut the Door”, and his conflict-entertainment approach in today’s influencer industrial scene. How did that come about?

A: I’m quite lucky to have worked with Rest of World, because they’re a media outlet that takes a deep look at how technology affects different societies. They also give writers a lot of room to explore unusual angles. So at the time, my editor asked if I could explore tech culture in Indonesia by looking into the influencers. I immediately thought of Deddy Corbuzier.

It was 2022, and Deddy had become one of Indonesia’s highest-earning influencers. He was already interviewing politicians, and I thought that was so bizarre. I felt that it wasn’t just a random moment; it symbolised a larger shift where influencers are gaining political power and influence, something that we might’ve underestimated. So, I pitched the idea to my editor: I wanted to interview Deddy and write about how his podcast and persona reflected this emerging phenomenon.

M: So what was it like interviewing him? How did he respond to the article?

A: It was…strange (laughs). I sat in the same chair where his guests usually sit—except this time, I was the one asking the questions. He definitely has that strong celebrity aura. But he really liked the article! At first, I wasn’t sure how he’d react, but he loved that I compared him to Joe Rogan. He didn’t see it as an insult at all—if anything, I think that’s exactly what he aspires to be: a divisive, influential figure who shapes public conversations. And he thinks this is completely normal in today’s online era culture, and that’s how people make money today.

“I feel like technology is one of the biggest stories of our time. It’s not just about scientific achievement.”

M: What do you think about his view on that? And what do you think about the spurt of platforms like his in our online landscape, and how the public navigates information from them?

A: I don’t think it should be normal! I think we seriously underestimate how much technology has altered the way we consume information. We’re still underestimating it, and we’re not questioning enough. We accept digitalisation and social media without really examining how they influence our behaviour, how they facilitate misinformation, and the implications that come with it.

And when you bring this up, people often dismiss you as being “anti-progress” or “anti-technology.” We’re told, “This is just how the world evolves; we have to adapt.”

But to me, that’s a temporary fix. Individuals can and should be smart about navigating online harms, but what about the tech developers? Why aren’t they held accountable for building safer, more responsible platforms in the first place? If we can build anything, why not build technology that doesn’t allow harmful behaviour to spread so easily? Those are the deeper issues I want to highlight in my reporting.

M: Some of us may be intimidated by the matter of technology due to the lack of understanding of it, when in actuality, the impacts are very close to our daily lives. But if you could explain to people in this situation, why should we pay attention?

A: I feel like technology is one of the biggest stories of our time. It’s not just about scientific achievement. Once a technology is released and mass-marketed, it collides with human elements—and that’s what I’m trying to dig into.

When we think about digital tech, we usually just think about the screens in front of us. But actually, the infrastructure behind digital tech requires enormous resources. We need massive data centres that use huge amounts of water and energy just to keep them running; and there’s also the mining of raw materials, all those chips and devices need metals that are dug out of the earth.

That’s why, during my reporting on electric vehicles and nickel mining in Sulawesi for Rest of World, it became so clear: when we talk about developing new technology, we also have to look at what goes into it—the raw materials, the energy needed not just to create it, but to mass-produce it and make it accessible for everyone. And a lot of times, to get there, we end up wrecking the environment in ways people don’t fully realise.

On the geopolitical side, leaders think that if they can control the next big technology, they can become global leaders too. That’s why there’s this race over EVs—countries fighting, trade wars happening. And now with artificial intelligence (AI), it’s the same—another tech that governments are scrambling to dominate. It’s the U.S. versus China all over again. In the end, technology doesn’t just affect the tech industry—it impacts everything, deeply and broadly.

M: The impact is to the point where we can’t just ignore it.

A: Exactly, and we shouldn’t [ignore it]. Because we, urban communities, are using technology without thinking anymore. But it turns out the impact is huge: our own lives are affected, and so are the lives of people in rural areas, where their environments are being destroyed because we need raw materials to manufacture our technological devices and digital infrastructure.

In the end, it affects everyone, and this isn’t reported in-depth or in a developing manner. You’ll maybe hear a quick news piece about people near a nickel mine complaining about the direct effects, but it’s not really explained why there’s such massive mining happening there, what it’s used for, or where it all ends up.

“I think the media will take further hits from AI, from our increasingly authoritarian government, and from its own inability to learn from its past mistakes.”

M: You brushed earlier about the AI development, and you told me that you’re working with the Jakarta Arts Council to educate the impacts of generative AI on artists. Can you tell us a little bit about that?

A: You know, I was very ready to hang up my journalist hat. I wanted to pivot fully into fiction writing. But then AI suddenly exploded, and I just couldn’t resist going into it.

With the Jakarta Arts Council, I’m working to raise awareness among creative workers and artists about how generative AI is impacting their work. So I’ve been writing opinion pieces and organising panel discussions with artists and writers in Jakarta to explore their concerns, frustrations, and fears around AI.

Because the way this technology is built is by consuming a massive amount of people’s work from the web—without permission and compensation. That’s literally the only reason this technology exists. If you talk about Facebook, the reason why we have so many problems today with misinformation and online abuse is that, from the beginning, ethics weren’t a priority. And now with AI, it’s the same story—how can you not expect consequences when a technology is born from violation, from a complete disregard for human artists?

The media coverage today is mostly just boosting it, like “Oh, we have to adopt AI as fast as possible!” But wait a minute—we need to talk about the problems first. Because if we rush it, we’ll just be repeating the same mistakes we made with social media. And once the problems are too entrenched, we won’t be able to fix them. So, that’s what I’m trying to work on with the Jakarta Arts Council, and there are a lot of other groups concerned about AI, too. So hopefully we can unite our voices.

M: On to that, how do you foresee the media landscape here evolving in the next few years?

A: I think the media will take further hits from AI, from our increasingly authoritarian government, and from its own inability to learn from its past mistakes. We can see now how many are jumping on the AI bandwagon to cut costs and lay off their staff, and repeating Big Tech’s narrative of how AI will save everyone, including the media industry.

The overemphasis on digital tools’ rainbow promises is unhealthy. The media’s inability to stand up to Big Tech directly contributes to further destruction of our information ecosystem, and thus, our democracy. The media is malnourished from the inside, and will struggle even more when facing obstacles such as misinformation and authoritarian governments.

M: Even so, do you think there’d be greater openness and dialogue in media and public discourse, or are we more likely to see tighter restrictions?

A: I do think there will be more restrictive regulations. There are already more restrictions right now than, say, ten years ago. Tempo journalists received direct threats and terror. Increased surveillance. Meanwhile, the government continues to involve celebrities and influencers in their public communication strategies.

So, the weakening of journalism and the media is not only being carried out by outright, direct violence towards journalists, but also through “soft” methods like staging shows and using influencers, because the illusion of free speech must be maintained.

In my opinion, as long as media leaders continue to misdiagnose the industry’s ailments and keep taking the wrong medicines, linking arms with the wrong parties, the media will not have the strength it needs to properly educate and inform the public—the very reason it exists in the first place.