In his Milan studio, Dery Rizkianto is quietly shaping a young label in one of the world’s fashion capitals. His approach draws from two distinct chapters: the research-driven discipline he absorbed in London, and the hands-on precision of Milan’s ateliers during his student days. The result is a design language anchored in couture sensibilities and the rigour of tailoring.

Earlier this year, he brought that discipline home to Jakarta with Easthedra—his latest collection, and the first to incorporate tenun. Woven by local artisans over months, the cloth is cut into clean, sculptural silhouettes that extend the conversation on how tradition can be worn.

Speaking over Zoom, Rizkianto reflects on adapting to different cities, the realities of running a small label abroad, and the weight—and possibility—of working with Indonesian craft for a global audience.

Manual (M): Hi Dery. To start, can you share a little bit about your upbringing and your earliest memory of fashion that led you to starting The Rizkianto?

Dery Rizkianto (DR): Not many people know this, but I grew up in Surabaya. And my love for fashion—along with losing my father at a young age—made me think seriously about my future, hopes and dreams. I’ve always believed that if you have a strong will, you can achieve anything.

M: You’ve lived and worked in Indonesia, London and Milan. How would you describe the way these experiences have informed your visual language?

DR: In the beginning, my family didn’t really take my interest in fashion too seriously. But I kept convincing my mom, and she eventually caved in. I went to the London College of Fashion before moving to Milan. Funny enough, Milan wasn’t part of my original plan. But during my time in London, I attended an open house for Istituto Marangoni with some Italian friends who were considering doing their master’s there. I got curious and asked about the differences in study methods between London and Milan.

In London, the workload was intense; we did a lot of research and spent most of our time in the library. Milan, on the other hand, was much more hands-on and practical. That approach appealed to me, so I applied, got in, and ended up moving there. Then COVID hit, which was especially challenging for fashion students. I had expected to spend more time in the studio, but the pandemic forced us to adapt and find creative solutions within those limitations.

Right now, I think the language of fashion has become increasingly global and diverse. So whether I’m in Indonesia, London or Milan, it’s important that my work always reflects the influence of the place I’m in.

M: What were the biggest differences between these cities, and how did that shape your design approach?

DR: I think a good designer needs to adapt to the culture you’re in. In London, I embraced the heavy research culture; it was intense, and I barely got any sleep because we spent so much time researching. Milan, on the other hand, felt more laid-back. But at the same time, I don’t think you can compare the two; both cities pushed me to become the best version of myself in different ways.

This is also quite different from my Asian background, where there’s a strong work ethic and a tendency to keep going non-stop. So wherever I am, I try to always adjust and adapt to the rhythm of the place.

“When working with traditional fabrics like tenun for example, it’s easy for the result to feel predictable, and there’s often an expectation of how it ‘should’ look. I wanted to challenge that further.”

M: The ‘Made in Italy’ label carries a global reputation for prestige and craftsmanship. How have you interacted with or been inspired by this approach to quality and detail in your work?

DR: I’ve always been very detail-oriented. My friends often call me a perfectionist, so producing high-quality work is important to me. Italy is renowned for its craftsmanship, and Indonesia has its own equally high standards, though expressed in different ways. You can’t compare them; each has its own strengths.

Italy’s craft tradition is more globally recognised, but working with tenun for my last collection deepened my appreciation for Indonesia’s heritage. It’s a process that can take months, and I had the chance to meet ibu-ibu and local artisans who have been weaving for generations. They not only shared their skills with me but also gave me books and stories that helped me understand the craft on a much deeper level.

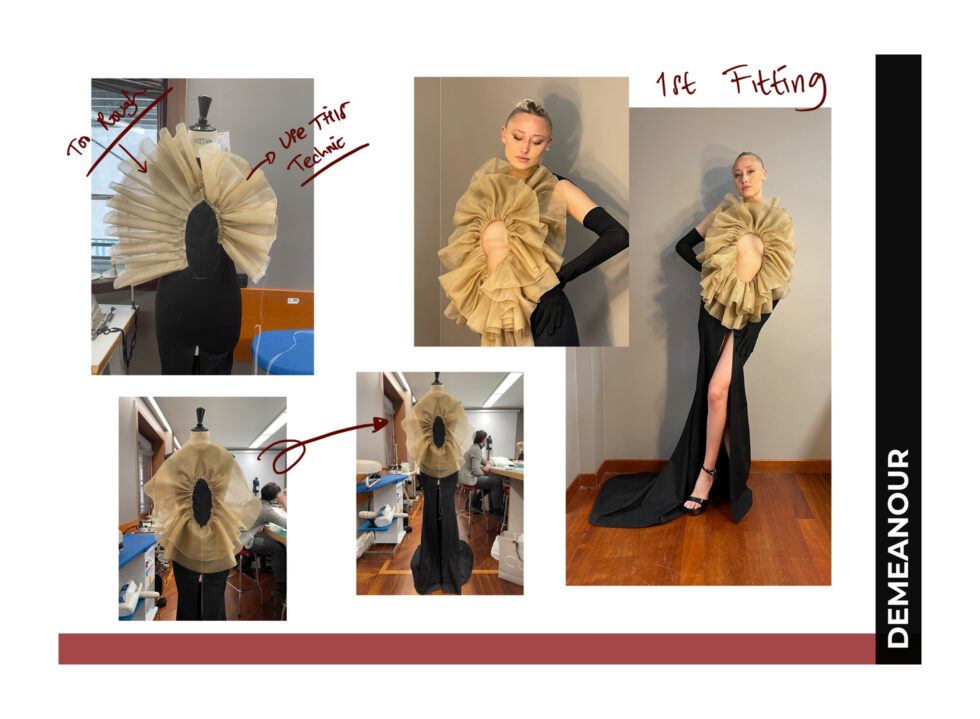

M: Let’s talk about your earliest collection, Demeanour. What was the inspiration behind that?

DR: It was my first collection in 2023. Golden Age Hollywood has always been close to my heart and continues to influence my work, even up until my most recent collection. I love this era because it was a time when fashion felt like it was truly evolving, and that spirit of growth has shaped my creative process.

I actually began developing the collection while I was still studying. After completing my course at Istituto Marangoni, I wasn’t quite satisfied with it yet, so I decided to continue my studies in Milan and focus on tailoring. During that time, I had the opportunity to participate in one of Italy’s biggest platforms for emerging talent, Fashion Graduate Italia, which selects students to showcase their work. I was grateful to be chosen and produced six looks for the show.

That experience opened a lot of doors. I had the chance to work with major stylists and celebrities, and even a few Hollywood names. Riding on that momentum, I decided it was the right time to launch my brand.

M: That’s an incredible start. Since that show, what’s been a defining moment or turning point for The Rizkianto that has helped shape the brand today?

DR: There have been a few milestones, but working with some of Italy’s top stylists stands out. I never imagined I’d have that opportunity. In Milan, or any major fashion capital, you’re not competing with other emerging designers but big fashion houses. So when I was approached to dress a well-known Italian actress, it was a huge moment for me. From there, stylists began sharing my work through word of mouth.

My biggest achievement so far would have to be working with notable names in Hollywood. In this industry, a lot of brands pay for exposure or for celebrities to wear their pieces, so I’m grateful that I didn’t have to do that; people have come to me because they’ve seen my work and believe in it.

As an emerging designer, breaking into a market like Hollywood isn’t easy. Last year, one of my dresses was supposed to appear at the Oscars. It wasn’t chosen in the end, as they went with a big [fashion] house instead, but just being considered for one of the biggest stages in the world was an honour for me.

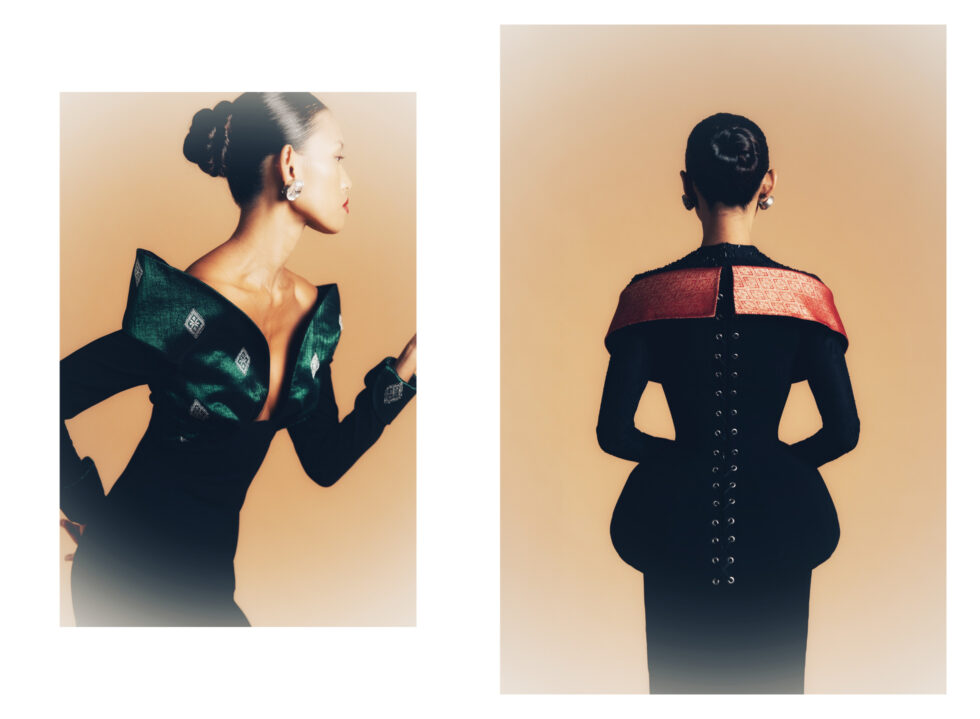

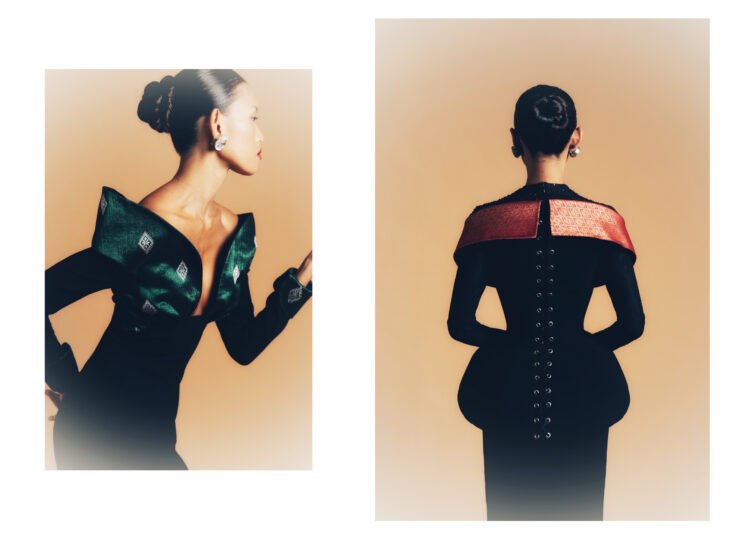

M: Let’s jump into your latest collection, Easthedra, which you presented in Jakarta. Tailoring has always been central to your work, and this time you combined it with Indonesian tenun for the first time. Could you share some insights into how the collection came together?

DR: Funny story, about two years ago, I met Dewi Ivo Rajasa, one of the founders of Cita Tenun Indonesia. She’d been following my work and asked why I didn’t explore tenun. She kept encouraging me to do something for Indonesia, but at the time, I was honest with her: I didn’t feel confident working with tenun. I wasn’t used to the textile or its colour patterns, and my market was still mostly in Europe.

Over time, she kept bringing it up. The last time I was in Jakarta, we met again, and she invited me to Galeri Cita Tenun. She picked a fabric, handed it to me, and asked me to make a jacket for her. In the process, I realised the fabric was actually quite versatile; you could push it in many directions depending on how you worked with it.

That’s when I decided to take on the challenge [of working with tenun]. I made it clear that I wanted to create my own design so it would still align with The Rizkianto identity. When working with traditional fabrics, it’s easy for the result to feel predictable, and there’s often an expectation of how the traditional textile ‘should’ look. I wanted to break that. Originally, I planned to present Easthedra at Salone del Mobile in Milan, but one thing led to another, and we realised Jakarta was a very fitting place for its debut.

M: I noticed that there’s an emphasis on structure on the neck and sleeves. Was there a new tailoring or couture technique you explored in this collection?

DR: I think Easthedra is more refined compared to my previous collections. Even though I had very little time (only two and a half months instead of my usual six to eight), I poured a lot of love, art, and work into it.

In terms of technique, I always incorporate couture methods into my collections, but my goal is to let people truly experience what couture is, especially in a more accessible way. For Easthedra, I experimented with a technique I had never tried before, and thankfully, it worked beautifully with tenun. I used highly structured fabrics and shapes, which makes the garments appear heavy, but when you touch them, they’re surprisingly light.

We apply many tailoring techniques, but trial and error is an integral part of any design journey. This becomes especially true when creating exaggerated or dramatic silhouettes, like the contoured, over-extended hip design featured in several looks. The challenge lies in achieving a structure that can hold its shape while remaining light and comfortable for the wearer. It was also my first time presenting work in Indonesia, so I wanted to create something different.

“I think the language of fashion has become increasingly global and diverse. So whether I’m in Indonesia, London or Milan, it’s important that my work always reflects the influence of the place I’m in.”

M: Would you say the feedback you received in Jakarta was different from Milan?

DR: The feedback was great. Even though the show was in Jakarta, I still heard from stylists and celebrities in Milan who follow my work on Instagram. The feedback was encouraging, many people told me they found it an unexpected and refreshing way to work with tenun. I’ve had strong support from both cities, but my biggest critic will always be myself. In Jakarta, because the audience included my family and childhood friends, it felt more personal.

M: With that out of the way, what are you currently working on? I heard you’ll be showing at Jakarta Fashion Week this year.

DR: Yes! For this next collection, I’m working closely with Cita Tenun Indonesia and local artisans to develop my own tenun. I really want to bring Indonesian fabrics to the global stage, and to do that, I have to merge them with an international sensibility. I don’t want people to immediately think, “Oh, this is very Indonesian” or “very traditional.” My aim is to create something unexpected, where you wouldn’t even realise at first glance that tenun is the main fabric.

M: That’s exciting! Do you think working as a Southeast Asian designer in Milan comes with its own set of challenges and advantages?

DR: In terms of challenges…I think it’s what I mentioned earlier about competing with big fashion houses. But the advantage is the exposure and opportunities that come with being here. The connections I’ve built have been invaluable. At the end of the day, I think people view you by your skills and your work, not where you come from.

M: I’ve noticed that your collections are often a focused set of around 10 looks. What’s the thinking behind that?

DR: As a young, emerging brand with a small team, I’m aware that growth doesn’t happen overnight. A tighter, more curated collection allows us to grow sustainably without overstretching ourselves. Beyond the seasonal collections, I also take on a lot of custom work, so we’re always on the clock.

M: How big is the team now? And is it part of your plan to have a team based in Jakarta, too?

DR: Right now, we’re about 10 people, all based in Milan, including designers and seamstresses. But I am planning to work more often in Indonesia, so I’ll need to build a small team here too. Wish me luck!

M: Having been used to the work culture in London and Milan, how did you find adjusting to the work environment and people in Indonesia?

DR: Working with seamstresses in Indonesia can be quite different; they’re not always familiar with the full process, and sometimes there’s a tendency to skip steps. I’ve had to explain that it doesn’t work that way. Even though we’re developing the collection here, I want to approach it exactly as I did in Milan. Naturally, the techniques and working methods can be very different. Indonesia has so many talented artisans, but I feel their skills aren’t always utilised to their fullest potential. In couture, especially, I think we’re still a bit behind. But that’s a challenge I’m willing to take on.

M: Right, I think sometimes people can be too focused on the results and miss the process?

DR: Exactly. And it’s not always easy to explain. Of course, skipping steps may save time, but that’s not the point. The value is in the process itself. I try to help them see and understand that. Sometimes I challenge them by saying, “Okay, try doing it your way and then my way, and we’ll see which one turns out better.” Eventually, they’ll admit it, but it does take time. We really need to build a deeper understanding of the process.

M: Thanks for sharing your thoughts, Dery, we’re looking forward to seeing your new collection at JFW.

DR: Thanks a lot! See you guys.